In posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), the gel that fills your eyeball separates from your retina. It’s a common condition with age. PVD can cause floaters or flashes of light, which you may ignore over time. Posterior vitreous detachment isn’t painful or sight-threatening. But you should see an eye specialist right away to make sure you don’t have another retina problem.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/posterior-vitreous-detachment)

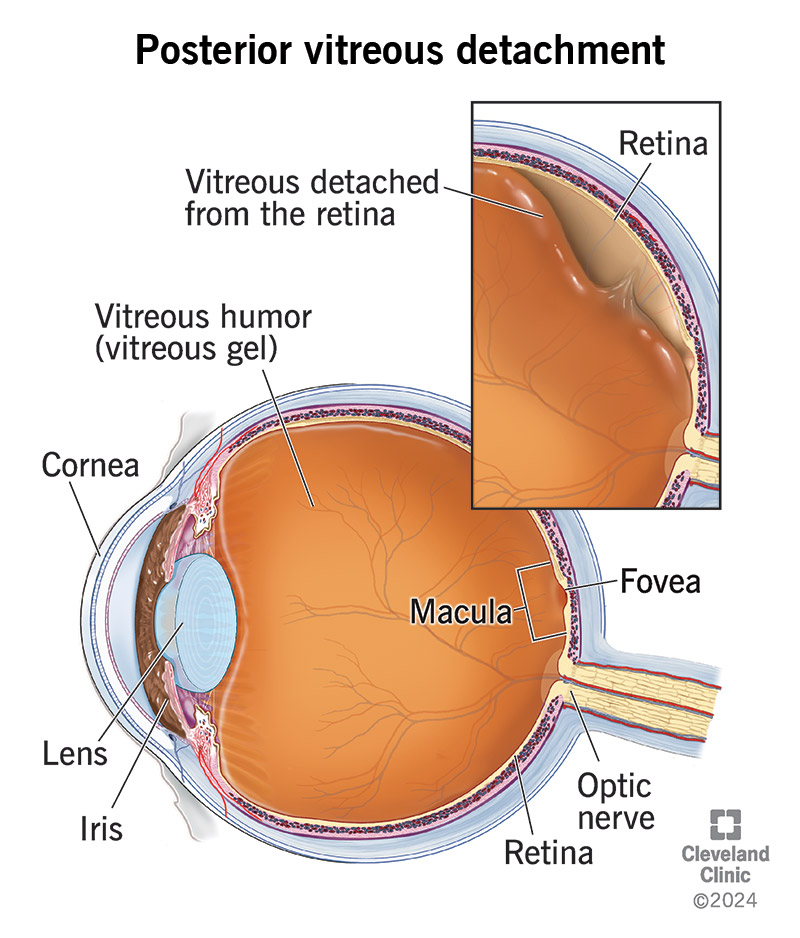

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is a common age-related eye problem that occurs when the gel that fills your eyeball (vitreous gel) separates from your retina. Your retina is a thin layer of nerve tissue that lines the back of your eyeball. It’s responsible for detecting light and turning it into visual images.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

With PVD, there’s often an increase in specks or shadows of gray or black in your vision. It may also make you see flashes of light, usually at the side of your vision.

PVD may evolve over time as the gel completely separates from the retina. Your floaters may change size and shape over four to six weeks. It’s recommended you consult with an ophthalmologist when you have new floaters.

Posterior vitreous detachment is a natural process that occurs as you age.

PVD is a very common, age-related condition. It’s estimated that 66% of people between the ages of 66 and 86 will develop the condition.

Vitreous detachment symptoms include:

Advertisement

If you experience the symptoms of posterior vitreous detachment, reach out to an eye care specialist. The symptoms are usually mild and become less noticeable within a few months as your brain learns to ignore them.

When you’re in your early 20s, your eye is filled with a gel-like substance called vitreous humor. With age, the vitreous humor increasingly turns to fluid. Without a solid structure, the gel collapses on itself and separates from the retina.

Posterior vitreous detachment is a natural and common age-related eye problem. It’s rare in people younger than 40, usually occurring after age 50. The chances of developing a detached vitreous increase as you get older. If you’ve had PVD in one eye, you’re more likely to develop it in the other eye. Certain factors make posterior vitreous detachment more likely, including:

PVD isn’t painful and it usually doesn’t cause vision loss unless you have a complication, like:

Complications occur in less than 15% of people with vitreous degeneration.

If you have posterior vitreous detachment symptoms, you should visit an eye care specialist (ophthalmologist or optometrist) right away. An eye exam can identify any serious problems and reduce the risk of permanent damage and vision loss.

The specialist will conduct a dilated eye examination. The specialist will put drops in your eye to dilate (widen) your pupil, then look inside using a few tools. The test is usually painless, other than maybe feeling a little pressure or a slight sting.

In rare circumstances when the specialist can’t see to the back of the eye, an ocular ultrasound may be needed. This painless test uses high-frequency sound waves to approximate eye anatomy.

Unless there’s a complication, posterior vitreous detachment doesn’t require treatment. To ensure you don’t miss any complications from PVD, you should have an eye exam when your symptoms start and again four to six weeks later.

During a follow-up eye exam, your provider will look for several things. First, your provider will check that nothing was missed during your PVD diagnosis. Second, your provider will look for any complications. There may not have been a retinal tear, for example, during the first exam, but it can be there during a future exam.

Surgery for floaters is rare due to the risk of surgical complications. But it’s possible in special cases. It’s recommended you seek the opinion of a vitreoretinal surgeon before pursuing surgery for floaters.

Advertisement

People with posterior vitreous detachment can usually go about their usual activities with no restrictions.

Although the condition doesn’t go away, floaters and flashes become less noticeable over time. It’s common to develop PVD in the other eye in the next year or two after your first diagnosis. If you experience symptoms in the other eye, you’ll need a repeat eye exam to be sure there isn’t a retinal tear or a detached vitreous in your other eye.

Most people don’t develop complications like a retinal tear. But you should have an eye exam to make sure you don’t have a more serious condition.

There’s no way to prevent posterior vitreous detachment. It’s a natural part of the aging process. But you should report any changes in your vision to an eye care specialist. They can detect other eye conditions and prevent complications.

Some techniques may help you cope with the floaters and flashes that come with posterior vitreous detachment, like:

Advertisement

Posterior vitreous detachment may sound scary, but fortunately, it’s not a serious eye condition. It’s a natural process that happens as you age. More than half of older Americans will experience it. While the condition itself isn’t serious, the complications from it can be. So, it’s important to see your eye care specialist if you have any symptoms so they can rule out or treat anything more serious.

Posterior vitreous detachment is a natural process. It happens when the gel that fills your eyeball separates from your retina. PVD can cause floaters or flashes in your sight, which usually become less noticeable over time. The condition isn’t painful and it doesn’t cause vision loss on its own. But you should see an eye specialist to make sure you don’t have another problem, like a retinal tear.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Your eyes are one of your most important senses. If something goes wrong, it can change your world. Cleveland Clinic can help treat all types of retinal disease.