Dravet syndrome is a rare type of epilepsy. Seizures may last longer than five minutes. It can also affect your child’s development, movement and behavior. Longer seizures may raise the risk of serious health problems. Your child’s care team will create a treatment plan to keep them safe.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

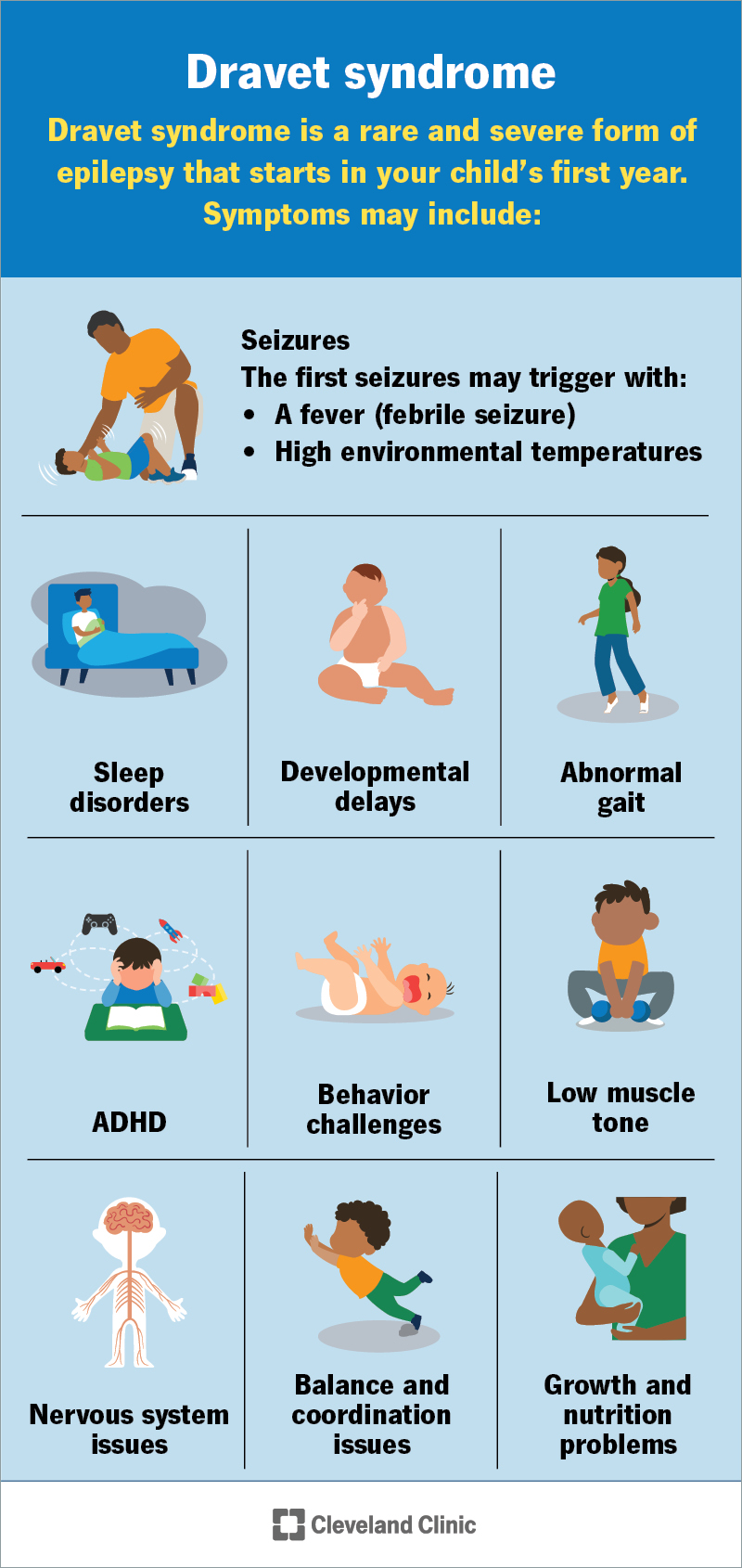

Dravet syndrome, previously known as severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI), is a rare and serious type of epilepsy. The first seizure often happens with a high fever and can last more than five minutes. It can lead to developmental delays, trouble with speech and language, and problems with balance or walking.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Long seizures can be dangerous, so care plans often include steps to stay safe and prepare for emergencies.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/dravet-syndrome)

A seizure is the first symptom. It often happens before your child turns 1 year old. The first seizure may:

After age 1, your child may have more seizures. These might happen without temperature changes.

Other symptoms may include:

A genetic change (variant) in a gene called SCN1A causes most cases of Dravet syndrome. This gene gives your body instructions to make sodium channels. These are tiny openings in cells that help carry electrical signals in your brain. These signals help brain cells talk to each other.

When there’s a change in the SCN1A gene, the sodium channels won’t work the right way. This can make it harder for your brain to control signals properly. It can lead to seizures and other symptoms.

Advertisement

Yes, Dravet syndrome is a genetic condition. This means it happens because of a change in a gene. Most of the time, the gene change happens by chance and isn’t passed down from a biological parent. But in rare cases, it can run in families.

Sometimes, a parent may carry the gene change in some of their cells but not all. This is called mosaicism. Other times, the condition can be passed down in an autosomal dominant pattern. This means only one biological parent needs to have the gene change for a child to inherit it.

Not everyone with the SCN1A gene change will have Dravet syndrome. Some people may have the gene change but won’t have any symptoms. Some may have other forms of epilepsy or different conditions, like genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+), focal epilepsy or familial hemiplegic migraines.

This syndrome can lead to serious problems. Some may be life-threatening. These may include:

Your child’s healthcare provider will explain which warning signs to watch for. They’ll help you make an emergency plan to keep your child safe.

Your child’s healthcare provider will do a physical exam, ask about their health and any past medical issues. Their provider will also ask about your child’s seizure history and any medicines they take.

They may order a blood or saliva test to check for changes in the SCN1A gene. They may also use imaging tests, like an MRI, or a brain wave test called an EEG. These early test results might look normal, so it can sometimes take time to get a full diagnosis.

The main goal of treatment is to reduce how often your child has seizures. As seizures can be different for everyone, care plans aren’t one-size-fits-all. Your child’s healthcare providers will create a plan unique to their needs. Treatment may include:

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves these medicines to treat seizures from Dravet syndrome after age 2:

These medicines come in different forms, like pills or liquid, to make them easier to take.

Your provider may tell you to avoid certain antiseizure medicines called sodium channel blockers. Examples include carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine and phenytoin. These can sometimes make seizures worse.

Advertisement

Rescue medications are emergency treatments for continuous seizures. Your child’s provider will also help you create an action plan for home or their school.

These medicines can help stop a seizure. Most rescue medications are benzodiazepines, like:

They come in different forms, like nasal sprays, rectal gels, tablets that dissolve in the mouth (wafers) or films placed inside the cheek (buccal films).

Let your child’s provider know if they have two or more seizures that last more than five minutes. Tell them if the first one happened before your child’s first birthday. It’s also important to mention if the seizure was triggered by a fever or heat. These could be signs of Dravet syndrome.

After a diagnosis, you’ll meet regularly with your child’s care team. Tell their provider if your child’s seizures get worse, like happening more often or lasting longer, even after starting treatment.

Their provider will explain what warning signs to watch for and what to do in an emergency. Call 911 or your local emergency services number if your child:

Advertisement

Your child’s healthcare provider can talk with you about their outlook. This can be different for each child. Kids with this syndrome have frequent, long-lasting seizures. These may become shorter and happen less often as your child gets older. Medicine may reduce how often seizures happen, but it usually can’t stop them completely.

Your child may need a little extra time to reach developmental milestones for their age. They might also need some help at school.

Also, your child’s care team may suggest seeing different specialists to support their needs. For example, a podiatrist can help with walking and may recommend special shoe inserts (orthotics). An orthopaedic surgeon might do a procedure to help with walking problems or spine issues like scoliosis.

There’s no cure right now. And there’s no way to prevent it, as it’s a genetic condition. But researchers are working on new treatments.

Children with Dravet syndrome have a higher risk of early death. This can happen from sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), long-lasting seizures or injuries. But many people live into adulthood.

Your child’s provider will give you the best information about what to expect. Every child is different, and statistics may not reflect your child’s unique situation.

Advertisement

Watching your child have a seizure can be scary. It’s even harder knowing they may have another one after they recover. This is part of living with Dravet syndrome.

Your child’s care team will help you understand what’s happening during a seizure. They’ll also help you create an action plan so you know what to do and who to call in an emergency. Having a plan can give you some peace of mind.

Treatment may lower how often seizures happen or make them less severe. Your child will see their care team often and build strong relationships with their providers. If you ever have questions or concerns, don’t wait, reach out. They’re here to support you.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Getting help for your child with epilepsy is your top priority. Cleveland Clinic Children’s experts create custom treatment plans to match your child’s needs.