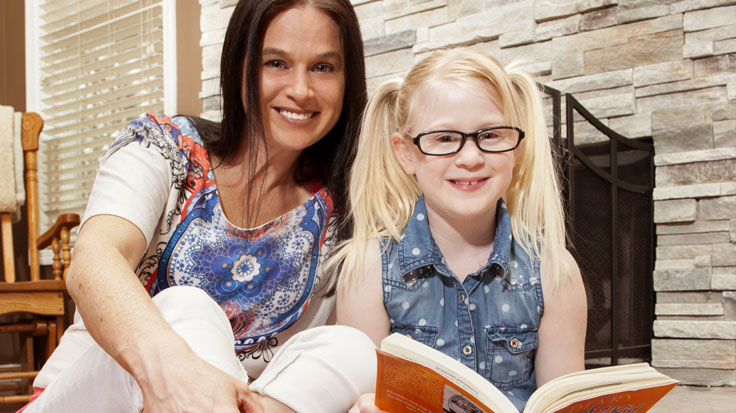

Nine-year-old triplet McKenzie Cornhoff is one of six kids in her family. She’s active and playful. She climbs trees. She loves grape Popsicles. She’s also a medical mystery.

During her spring break from school in 2014, she came down with a stomach virus — possibly the same one her siblings endured. They recuperated in a day or two, but not McKenzie. Her belly became hard and swollen, causing severe pain.

Something was wrong,” says her mother, Stacey Cornhoff. “Her lips were gray; her legs were gray. I went to pick her up, and she collapsed.”

Stacey rushed her daughter to the Emergency Department at Cleveland Clinic Twinsburg Family Health and Surgery Center, just 5 minutes from their home.

“All these doctors and nurses came into the room, examining McKenzie and asking me questions,” says Stacey. “The next thing I knew, they said they had to transport her by helicopter to Cleveland Clinic’s main campus — and she needed to go now.”

Cleveland Clinic Children’s pediatric surgeon Anthony DeRoss, MD, met McKenzie minutes later, when she landed at main campus with the Cleveland Clinic Critical Care Transport (CCT) team.

“Her presentation was shocking,” he remembers. “Her abdomen was so swollen that it was cutting off circulation. She was in septic shock.”

Dr. DeRoss performed emergency surgery, expecting to find a bowel obstruction or dead intestine. He found neither — just a very irritated stomach and small intestine that had stopped working.

“They comforted us through this whole journey ... Of course, they were always coming in to check on McKenzie. I give their care five stars."

“All we could do was leave her abdomen open, allowing her organs to decompress and her blood to circulate,” he says. “We put a temporary dressing over her belly and waited.”

McKenzie spent the next eight days in intensive care. Test after test showed no evidence of disease, except norovirus — a common cause of “stomach flu.”

“Why it did what it did to McKenzie, they can’t understand,” says Stacey. Once the swelling subsided, Dr. DeRoss closed McKenzie’s abdomen. Signs of the virus were gone, but recovery would take four more weeks.

“Each day, we’d see signs of hope,” says Stacey. “McKenzie started to sit up, and then slowly eat a Popsicle. Therapists tried getting her to walk.”

A highlight for McKenzie was spending time with the hospital’s child life specialists. They’d care for her — playing, chatting, braiding her hair — when Stacey needed to be home with her other children.

Stacey also raves about the support that she and McKenzie received from the medical teams.

“They comforted us through this whole journey. They’d encourage me to get rest, bring me coffee or just listen if I needed to talk,” she says. “Of course, they were always coming in to check on McKenzie. I give their care five stars.”

It’s been two years since McKenzie’s illness. Her only memory is the scar on her belly.

“We took her back to Cleveland Clinic Twinsburg when she got home, to thank them for taking such good care of her,” says Stacey. “They knew her right away.” The Twinsburg emergency team and the CCT crew had been checking on McKenzie all along, throughout her stay at main campus.

“I was amazed that these people were so concerned and still cared about her,” says Stacey. “I’m so grateful to have Cleveland Clinic right here in our city. They helped save my daughter’s life.”

As for McKenzie, she’s dressed up as a doctor for Halloween the last two years. “She’s a survivor,” says Stacey. “She’s going to succeed in life and do something amazing.”

Related Institutes: Cleveland Clinic Children's