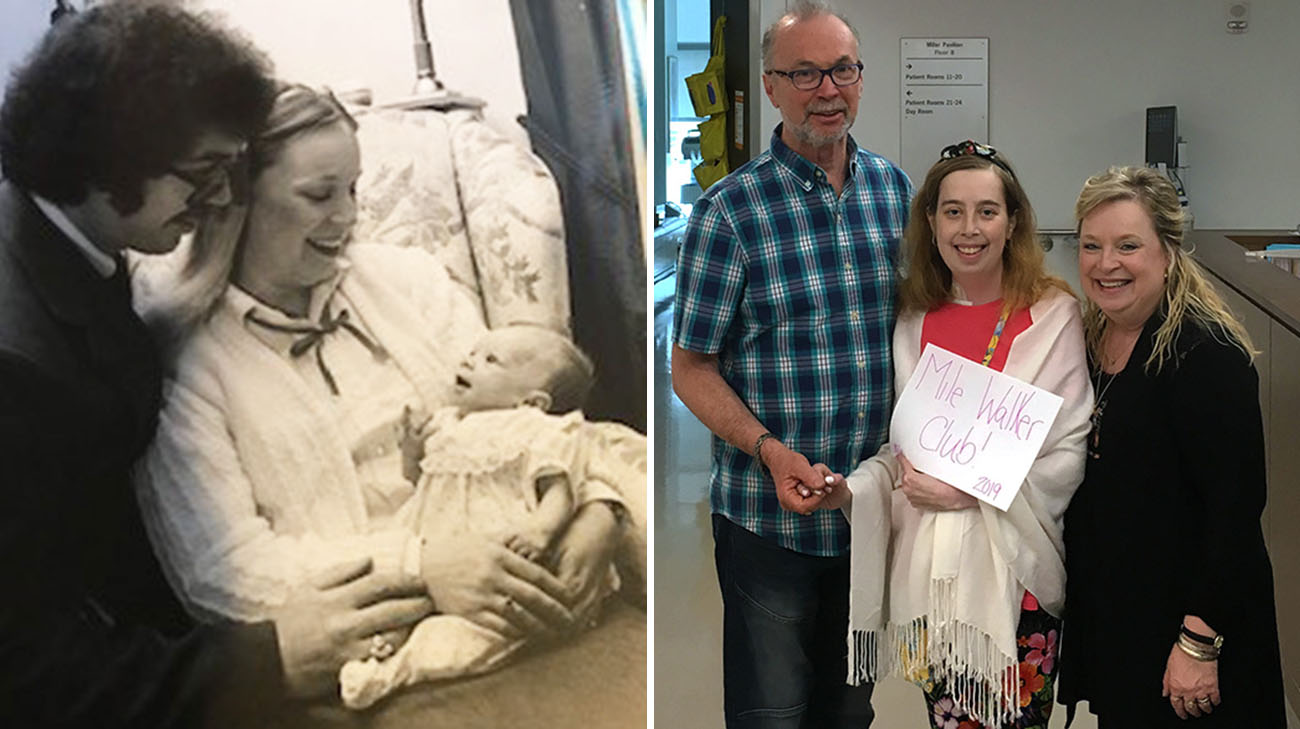

1983 proved to be the perfect birth year for Jessica Fletcher. Before then, most babies born with a congenital heart defect known as hypoplastic left heart syndrome typically died in the first week of life, or shortly thereafter. But in 1983, just days after her birth, Jessica became one of the first pediatric patients at Cleveland Clinic to successfully undergo the Norwood procedure, a then-revolutionary operation that re-routes blood flow to and from the heart to avoid the underdeveloped left ventricle.

“Babies born with this disease basically have half a heart. And before the early 1980s, almost all of them died,” explains Kenneth Zahka, MD, a Cleveland Clinic Children’s cardiologist who has overseen care for Jessica, now 36, since 2014. “But at every step in her journey, Jessica has been up to the challenge. She’s been a remarkably functional young woman.”

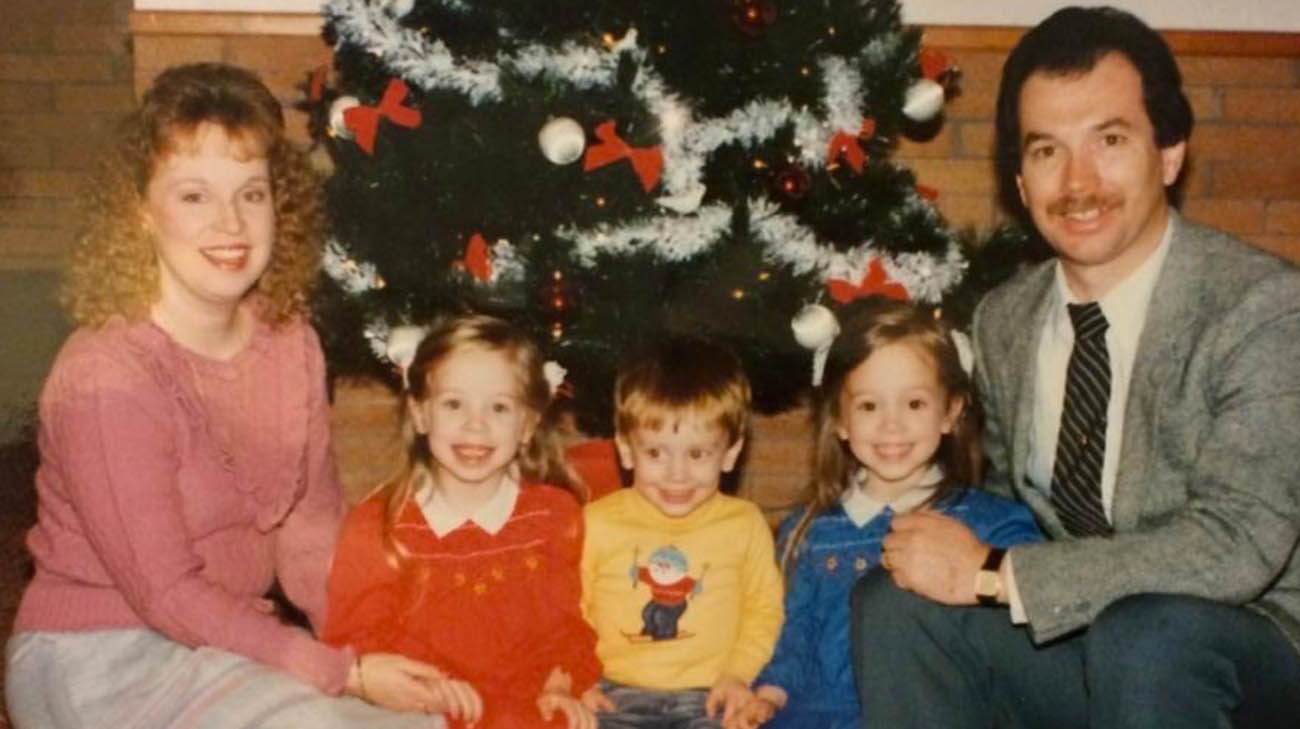

Jessica (in red dress), with her sister, brother, mom and dad. Days after Jessica's birth, she underwent a procedure that re-routed blood flow to and from her heart. (Courtesy: Jessica Fletcher)

Jessica’s most recent challenge occurred in 2019, when she underwent a successful heart transplant, which for many hypoplastic left heart syndrome patients is the fourth – and most dramatic – stage of surgical treatments typically required.

Following her initial surgery in 1983, Jessica underwent the Glenn operation about a year later, and the Fontan operation at age 22. The latter made her strong enough to attend Valley Forge University and pursue a career as a children’s minister at a church in Newcomerstown, about 20 miles from her hometown of New Philadelphia, Ohio.

Both the Glenn and Fontan operations, which are timed to coincide with lung development, furthered the ability of Jessica’s heart to function despite lacking a right ventricle. However, over time, the added strain on the heart can ultimately lead to its failure. Jessica first noticed related symptoms in 2018.

Jessica, with her nieces, while receiving care at Cleveland Clinic. (Courtesy: Jessica Fletcher)

“It became increasingly difficult to breathe, especially deep breaths. It felt like there was a weight sitting on my chest, and also, I began to retain some fluid in my legs,” Jessica recalls. “Just trying to do simple tasks like walking from my bedroom to the living room was challenging. It wasn’t getting better and we had to do something.”

First, Cleveland Clinic cardiac surgeons inserted a pacemaker to better control Jessica’s problematic heart rhythms. However, that failed to improve her condition, and Jessica was asked if she wanted to pursue the only option that remained: a heart transplant.

“I was a little bit scared. Heart transplant was a route I was hoping I wouldn’t have to go,” says Jessica. “For me the decision came to this: Do I want to watch my nieces and nephews grow up? Or do I want to let them watch their aunt pass away way too young? I can’t do that to them or to myself.”

Once she was approved for placement on the United Network for Organ Sharing transplant list, Jessica was hospitalized. She was too weak to live at home. Her stay lasted 125 days including time spent in post-transplant recovery. After a few months of waiting, Jessica suddenly got the word a suitable heart had been found.

Jessica's family welcoming her home, after she underwent a heart transplant. (Courtesy: Jessica Fletcher)

Thus began the most dangerous phase in her odyssey, as cardiovascular surgeon Robert Stewart, MD, and cardiac surgeon Michael Zhen-Yu Tong, MD, readied Jessica for what they knew would be a challenging transplant operation.

As expected, Dr. Stewart encountered significant scarring in the veins, arteries and other tissues surrounding Jessica’s heart. “In the case of single ventricle patients, like Jessica, they have really unique anatomy. If you take someone with a failing right ventricle, and all this scarring, it becomes very scary. The clock is ticking, because we can only keep the new heart on ice for a few hours.”

Jessica’s poor condition forced Dr. Stewart to try an uncommon procedure – inserting a cannula, a thin tube to facilitate the cardiopulmonary bypass phase of the transplant, into her poorly-constructed right ventricle. “It’s a sign of how desperate we were. We were out of options,“ he adds. “But it stabilized her blood pressure. It worked perfectly.”

Twelve hours after beginning – more than double the length of a typical heart transplant – the operation was complete. Soon after, Jessica continued her recovery in the home of her parents, Larry and Ruthie Fletcher, who are retired co-pastors. With the blessing of her doctors, Jessica is now strong enough to resume children’s ministry.

Jessica can now spend more time doing the things she loves, including spending time with one of her nieces, Brielle. (Courtesy: Jessica Fletcher)

“I’m back to normal,” exudes Jessica, who recently purchased a home. “Now, I’m able to do everything – and even more than before – without even the slightest bit of difficulty.”

According to Dr. Zahka, Jessica – one of his oldest hypoplastic left heart syndrome patients – is inspiring, for physicians and other patients. “She is an amazing success story, especially for someone born in 1983 with her condition. Despite everything she has been through, she has remarkable vibrancy. She’s a real trailblazer.”

Register with Lifebanc to become an organ donor.

Related Institutes: Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family), Cleveland Clinic Children's