Edward Liebler, a 78-year-old retired veterinarian, perfectly understood his predicament: His quality of life had greatly decreased because he needed a heart valve replacement, but he was considered “high risk,” limiting his surgical options.

Previous open-heart surgical procedures in recent years for a leaky heart valve only brought temporary relief, and now Edward could barely walk and found it extremely difficult to breathe. He was in no condition for another major operation to treat his life-threatening condition — tricuspid valve regurgitation, which causes blood that should flow out of the heart and into the lungs to flow backward, spilling back into the heart.

Luckily, Edward was the perfect candidate for a new, minimally invasive procedure using a special kind of self-expanding valved stent that was pioneered by a team of Cleveland Clinic surgeons and researchers, led by surgeon José L. Navia, MD, a member of the Miller Family Heart & Vascular Institute.

“This is a step forward in the treatment of tricuspid regurgitation,” Dr. Navia said.

Edward, who traveled to Cleveland Clinic from Lansing, Michigan, for the surgery, said he felt it was his only hope. “I decided we’d better try it,” he said.

And he’s glad he did. More than seven months after Dr. Navia made a tiny incision in Edward’s neck and used his jugular vein as the passageway to implant the tricuspid atrioventricular valved stent (AVS) into his heart, Edward feels better than he has in years.

Cleveland Clinic surgeons were the first in the nation to perform this innovative heart valve surgery through the jugular vein. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

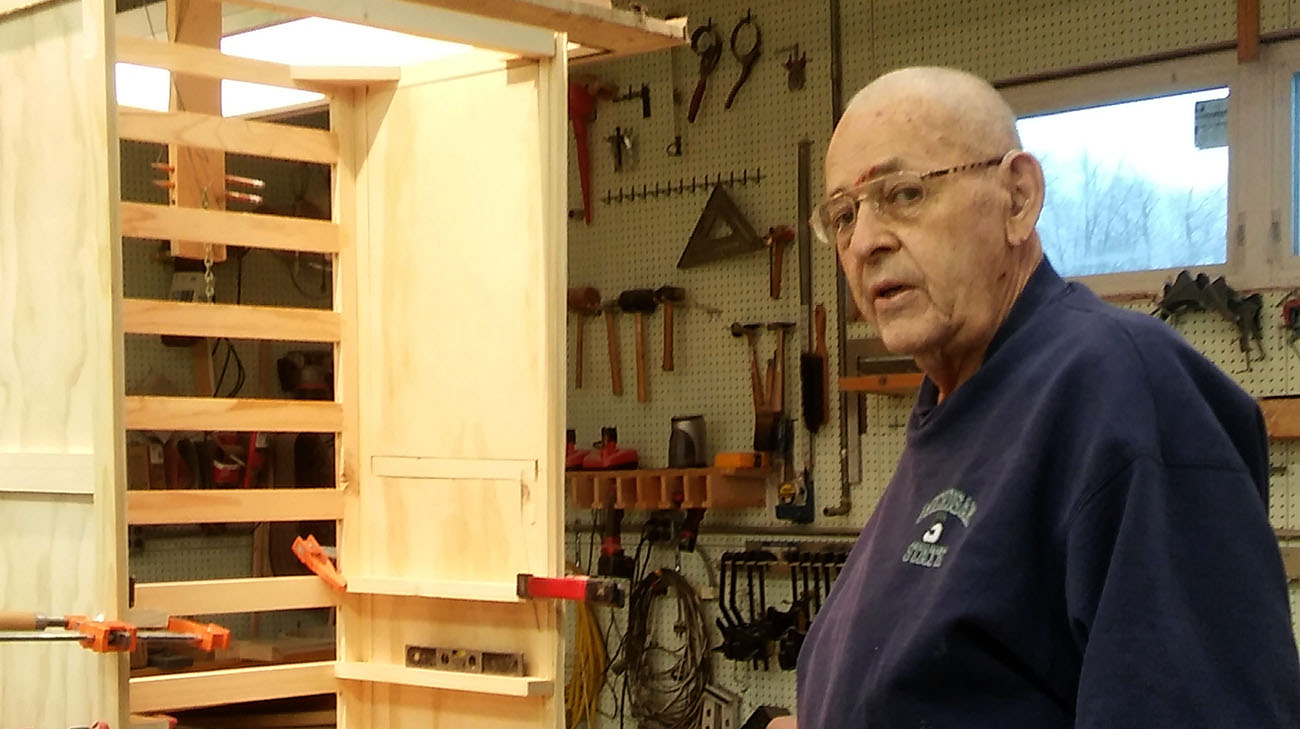

“I have a wood shop where I build short wave radios, and now I can work in the shop all day,” Edward said. “The procedure is a terrific advancement in science. It’s made a tremendous improvement in my life.”

Cleveland Clinic surgeons successfully performed the nation’s first implantation of the AVS in November 2016 in a 64-year-old woman with a long history of severe tricuspid regurgitation. Edward was the second patient at Cleveland Clinic to receive the surgery. FDA approved the AVS in 2016 for expanded access (sometimes called “compassionate use”), which is used outside of a clinical trial of an investigational medical product.

The distinctive aspect of the procedure is that the AVS can easily be threaded through the jugular — a vein collecting blood from the brain, parts of the face, and the neck — to reach the tricuspid valve, which was the faulty valve causing a back flow of blood into the right side of Edward’s heart instead of it going to the lungs. The AVS is “strapped” into place and restores normal function.

The AVS can be threaded through the jugular vein to reach the tricuspid valve. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

Tricuspid valve regurgitation is a very serious condition, Dr. Navia explained. Over time, all major organs suffer from the low-blood-flow condition, and the heart ultimately fails.

“The ideal candidate is a patient like Edward, with a high risk of complications or death from open-heart surgery,” Dr. Navia said. “Now, he has almost normal heart function. I’m extremely happy with the result.”

Currently, in 2018, the AVS procedure is only approved for high-risk patients like Edward, but Dr. Navia believes it has potential use for patients who aren’t as sick but would nevertheless benefit from less invasive surgery. He said plans are under way for a clinical trial of low-risk AVS use in the future.

As for Edward’s future, he has plans to supplement his hobbies by adopting a puppy sometime soon. His previous dog had been his steady companion since his wife, Constance, passed away in 2009.

“I feel like I can take care of a puppy now,” Edward said.

Related Institutes: Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family)