If you have an upper limb amputation or a congenital limb difference, you might be interested in a prosthetic arm. Different types of prosthetic arms serve different purposes.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/prosthetic-arm)

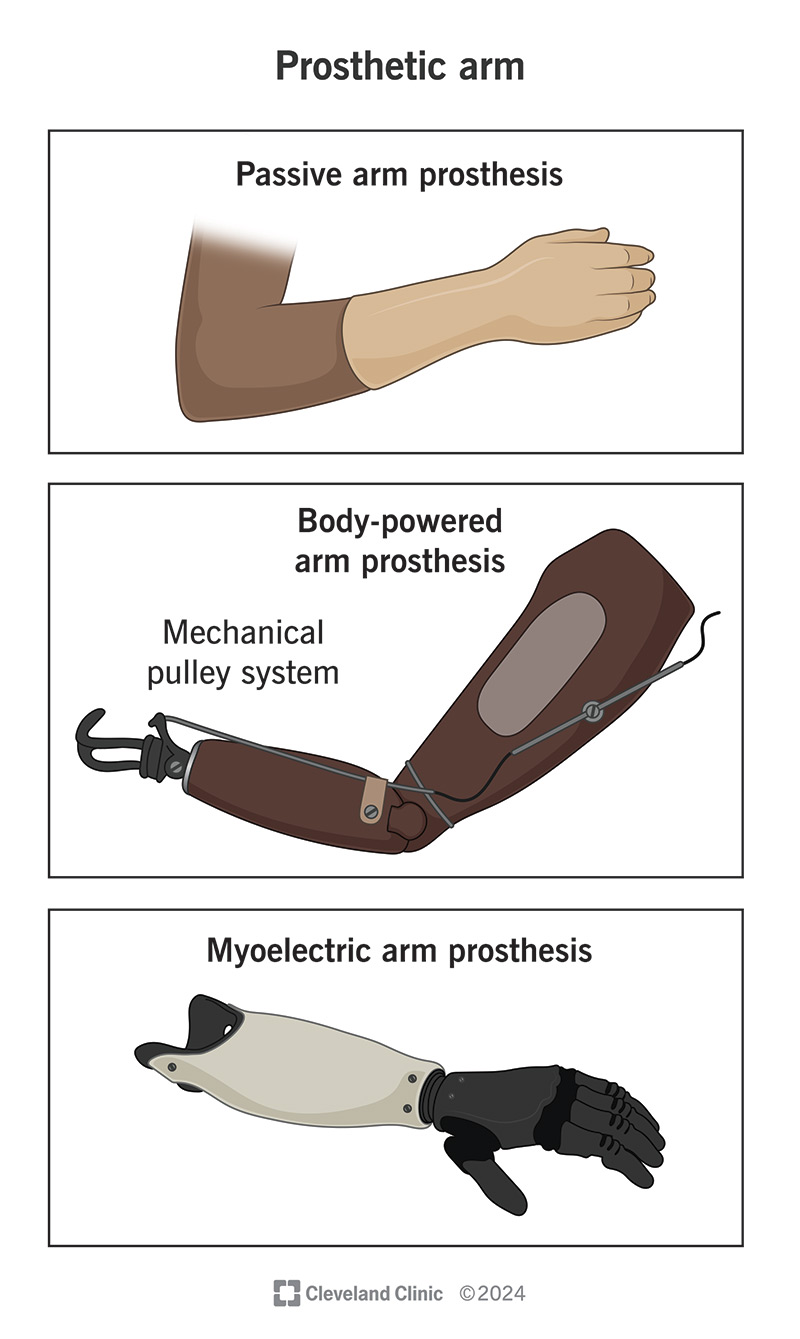

A prosthetic arm, or upper limb prosthesis, is an artificial replacement for your natural arm. It can replace part or all of your upper limb, from your hand, wrist and forearm to your elbow, upper arm and shoulder. Prosthetic arms can be passive, like a mannequin arm, or high-tech, like a robotic arm.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

You might be interested in an upper limb prosthesis if you’ve had an arm amputation or you were born with a congenital limb difference that affects its appearance and/or functionality. Different types of prostheses are available for different types of upper limb amputations and limb differences, including:

Different types of prosthetic arms serve different purposes. Some are more cosmetic, while others are more functional. Some are designed for everyday tasks, and others are designed for specific activities. If you have an absent arm or arm asymmetry, you might have use for several types of prosthetic arms.

Different types of prosthetic arms replace different parts of your limb as needed. You might need a prosthesis with a shoulder joint, elbow joint and/or wrist joint and a prosthetic hand or other terminal device. Different types also have different purposes and ways of functioning. These types include:

Advertisement

A passive arm prosthesis doesn’t function like a human arm, but it can look like one. You can get a custom, lifelike silicone arm (called a silicone restoration) that’s modeled and painted to look just like a natural arm. You can usually position it a few different ways. It’s a popular option for social functions.

A body-powered arm prosthesis is a mechanical device that operates using a type of pulley system. Cables connect the device to muscles elsewhere on your body, such as your shoulder. You activate these muscles to make the device move. Typically, it has a tool or a claw at the end that can open and close.

Body-powered prostheses are a good option for repetitive tasks and hard manual labor. They’re hardy and weatherproof and don’t need a lot of calibrating to work. The cable and harness system provides sensory feedback when you use it, so you don’t have to watch your prosthesis to know that it’s working.

If you need a prosthesis to perform a specific job, sport or hobby, you can get one specifically designed for that purpose. A prosthetist will work with you to design a prosthesis that functions exactly as you need it to. They can customize what’s on the end of it, how it moves and how much weight it can bear.

Activity-specific prosthetic arms can allow you to work with specialized tools, operate machines or work out. They’re easy to swap, and you might use different ones for different activities throughout the day. For example, you might use one type at work and another type at home or while pursuing a hobby.

A myoelectric arm prosthesis is an electronic device that operates through electrical impulses generated by your muscles. (Myo- means muscle.) You learn how to squeeze your muscles to trigger the device. Electrodes on your skin read your muscle contractions and signal to the device to make the joints move.

This electrical process uses less force than a body-powered prosthesis, so it’s less stressful on your muscles over time. It can also allow for much more fine-tuned movements. Myoelectric arms have articulating joints, and they typically end in a bionic hand with individually articulating fingers.

This type of prosthesis can enable you to perform a wide variety of everyday tasks. But it’s not always the most practical option for every task. It takes time to calibrate the device to perform the movements you want and skill to initiate complex movements. It’s not ideal for physically stressful work conditions.

Advertisement

Still, a myoelectric arm is a versatile option that can serve both practical and aesthetic purposes. It can look lifelike with a custom silicone overlay, or you can rock a futuristic, robotic look. Those who’ve mastered their bionic arm have relearned how to drive, type on a computer and play the piano with it.

Hybrid prosthetics combine myoelectric functions with body-powered ones. For example, a hybrid arm might combine a body-powered elbow joint with a myoelectric hand. This gives you the fine grip control of an articulating hand when you need it, along with the quicker and easier action of the arm when you don’t.

Acquiring your own upper limb prosthesis and learning to use it is a huge undertaking. It will take time, practice and patience on your part. And you can expect to get to know your healthcare team really well.

Here’s a brief breakdown of the steps involved:

Advertisement

Not everyone with an upper limb deficit chooses to use an arm prosthesis. Some people learn to adapt in other ways — for instance, by using other body parts. A prosthesis is usually heavy, and it takes effort to learn how to use it. Some might feel that the practical benefits of a prosthesis don’t outweigh the costs.

But even if you aren’t overly concerned with the practical benefits of a prosthetic arm, there are health benefits to consider. Using a prosthesis helps your body balance its workload better and distribute stress more evenly among your muscles. Not using a prosthesis can cause you to overuse your opposite side.

This can lead to risks like:

Of course, using a prosthetic arm also comes with potential risks and side effects, including:

These risks are mostly avoidable with proper fitting, training and maintenance. It’s also important to keep in mind that you’ll need to work with a physical therapist and occupational therapist to learn adaptive skills to compensate for your limb deficit — whether you decide to use a prosthesis or not.

Advertisement

A lot of variables can affect how long it takes to adapt to your new prosthesis, including the type you have, the way you practice, what you want to use it for and any complications you might be having.

Your physical therapist and/or occupational therapist will work with you to design a schedule for practicing skills and exercises that’s customized to your needs. This part can take up to a year.

Learning to use different muscles in different ways to achieve specific actions takes time. Learning to program a bionic arm and toggle between the various movement patterns can take even longer.

While you’re learning to use your prosthetic arm physically, you’ll also be adapting to it mentally and emotionally. Remember to practice patience and self-compassion. This process has its own timeline.

When you and your healthcare team feel you’ve successfully adapted to your new prosthesis, you may not need to continue with physical therapy. Some people do, though — like keeping a physical trainer.

In any case, your relationship with your prosthetist is likely to be a long-term one. You’ll need adjustments and repairs to your prosthesis over the years, as your practical and physical needs may change.

All prosthetics have an expiration date, and you’ll need to repeat the fitting process when that date arrives. Since technology continues to evolve, you may also decide to upgrade your prosthesis before then.

Be sure to call on your healthcare team if discomfort or complications related to your prosthesis develop. Your prosthetist is an important part of your healthcare team. They’ll advise you on treating and preventing complications.

Target muscle reinnervation (TMR) is a new and evolving surgical technique for those undergoing amputation surgery — especially those who are interested in using a myoelectric arm prosthesis.

During amputation surgery, major nerves are severed, and sometimes, the severed nerve endings cause pain. They can develop painful neuromas or trigger phantom limb sensations. TMR can prevent this.

During TMR, a surgeon skilled in nerve work redirects these severed nerves to other muscles in your body. Repairing and grounding the nerve endings can prevent neuromas and chronic pain syndromes.

Redirecting the nerves to other target muscles in your body can also help you operate a myoelectric arm prosthesis. You can train yourself to activate these new muscles in order to operate the prosthesis.

Prosthetic arm technology has come far in recent years, and modern prosthetics are more functional and versatile than ever before. You’ll be inspired by how much you can do with an upper limb prosthesis if you’re determined to learn how. And your healthcare team can’t wait to help you get there.

But for all this progress, and the innovations still to come, a prosthesis isn’t the same as a natural limb. And there’s no denying the difficulty of substituting a natural limb for a prosthetic one. Your healthcare team knows this, too. When feelings arise, they’ll remind you to balance determination with gentleness.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

From sudden injuries to chronic conditions, Cleveland Clinic’s orthopaedic providers can guide you through testing, treatment and beyond.