Pyloric stenosis is a condition that affects your infant’s pylorus, the muscle at the end of the stomach leading to the small intestine. When their pylorus thickens and narrows, food can’t pass through. Pyloric stenosis symptoms include forceful vomiting, which may cause dehydration and malnourishment. Surgery can repair the problem.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/4524-pyloric-stenosis)

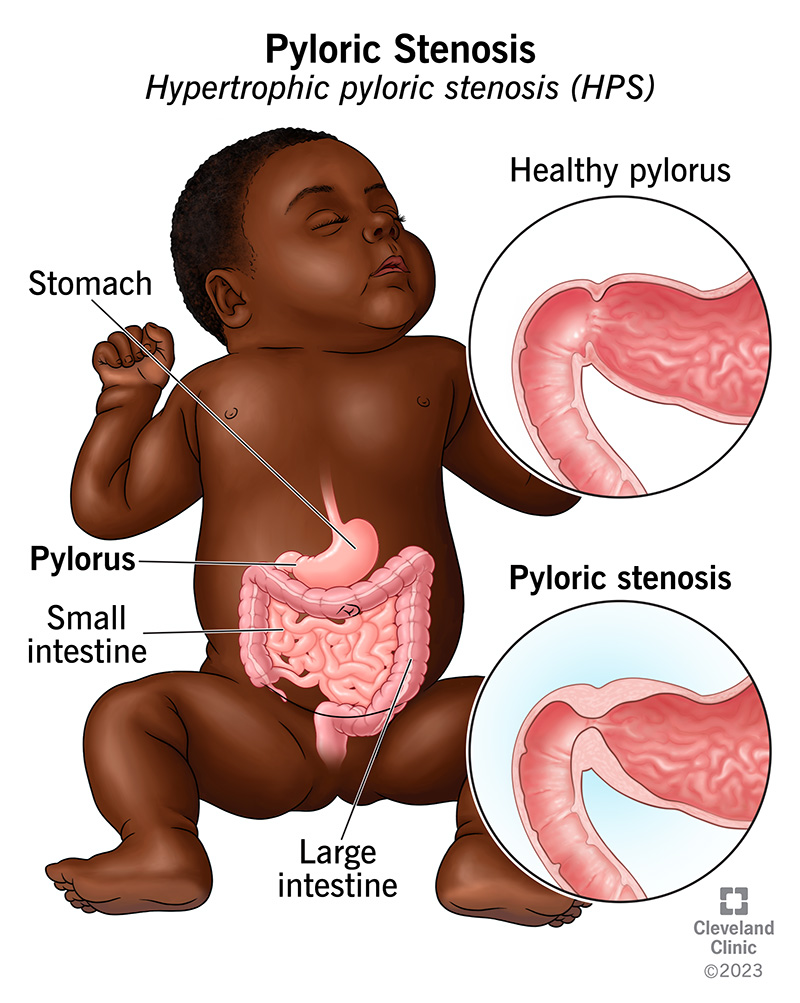

Pyloric stenosis is the thickening and narrowing of your baby’s pylorus, which is the muscular opening between their stomach and their small intestine. The full medical term for this condition is hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS):

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

HPS causes projectile vomiting and can lead to dehydration in babies. Fortunately, surgery can repair this issue.

Your pylorus is a muscular sphincter (a muscle that opens and closes). It’s located at the end of your stomach, where your stomach meets your small intestine. Your pylorus contracts (closes) when your stomach is digesting food and liquid. It then relaxes (opens) to let food and liquid pass into your small intestine.

When the pyloric muscle is too thick, it narrows the passageway. Liquid and food can’t move from the stomach to the small intestine. A baby with pyloric stenosis often forcefully vomits since formula or breast milk can’t leave their stomach. Many babies have difficulty gaining weight because they have many episodes of vomiting.

Babies with pyloric stenosis may vomit after every feeding or after just some feedings.

Babies usually aren’t born with pyloric stenosis. The thickening of their pylorus starts to happen in the weeks after birth.

Pyloric stenosis symptoms usually start when your baby is between 3 and 6 weeks old. But it can take up to five months for symptoms to become apparent. If you notice symptoms, talk to your baby’s healthcare provider. It’s best to treat HPS before your baby becomes dehydrated and undernourished.

Advertisement

In rare cases, older children can get a pyloric obstruction — something blocking the passage through their pylorus. Usually, a peptic ulcer is the cause in older children. Sometimes, a rare disorder such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, which inflames the stomach, can cause the condition.

Pyloric stenosis affects 1 to 3.5 out of every 1,000 newborns. It’s the most frequent condition requiring surgery in infants.

Pyloric stenosis symptoms typically start when your baby is between 3 and 6 weeks old. Infants with pyloric stenosis may eat well but have these symptoms:

Most babies appear otherwise healthy. Parents may not notice something’s wrong until babies get very dehydrated or undernourished. Babies may also start to get jaundice, when the skin and whites of their eyes become yellow.

Many babies spit up a little after they eat. These dribbles are common and usually nothing to worry about. Forceful or painful projectile vomiting is a sign of a more serious issue. Talk to your baby’s healthcare provider if your baby vomits after eating.

Scientists don’t know the exact cause of pyloric stenosis. However, genetics and environmental factors may play a role.

Risk factors for pyloric stenosis include:

Your baby’s healthcare provider will ask you about your baby’s eating habits and perform a physical exam. Sometimes, providers can feel an olive-sized lump in your baby’s belly (abdomen). That’s the thickened pyloric muscle.

Advertisement

Your baby’s provider may recommend a blood test, as well. This test can tell if your baby is dehydrated or has an electrolyte imbalance from vomiting. Electrolytes are minerals that keep your baby’s body working the way it should.

If your baby’s healthcare provider doesn’t feel a lump in their belly or wants to confirm the diagnosis, they may want to look for the pyloric stenosis on ultrasound. During an abdominal ultrasound:

Sometimes, even a physical exam and ultrasound don’t show any problems. If this happens, your baby’s provider may recommend an upper gastrointestinal (GI) series:

Pyloric stenosis treatment involves a type of pyloroplasty surgery called pyloromyotomy. After diagnosing pyloric stenosis, your baby’s surgeon will discuss the surgery with you.

Advertisement

Infants with pyloric stenosis often have dehydration because they vomit so much. Your baby’s provider will make sure your baby is properly hydrated before performing surgery. Your baby will probably need fluids through an IV, which they’ll receive at the hospital. Your baby may need a blood test to check their hydration during this time to make sure it’s improving.

Your baby won’t be able to have milk or formula starting six hours before surgery. Keeping them off these fluids reduces the risk of vomiting and aspiration (breathing in vomit) while under anesthesia.

During pyloric stenosis surgery, your baby’s healthcare team will:

The procedure usually takes less than an hour.

Your baby will likely need to stay in the hospital for one to three days after surgery. Here’s what you can expect:

Advertisement

Babies can still vomit after pyloric stenosis surgery. It doesn’t mean they have the condition again. Vomiting may be because of:

If your baby continues to vomit a lot, they may need more tests. Their care team will continue to work to correct any vomiting problems.

The outlook for babies with HPS is very good. Most children don’t have long-term problems after successful pyloric stenosis surgery. They eat well, grow and thrive.

In rare cases, the pylorus is still too narrow after surgery. Surgeons may perform a second operation to cut it more.

With treatment, infants experience no long-term issues later in life. In follow-up studies, people who had pyloromyotomy surgery as babies had no trouble with gastroesophageal reflux or other gastrointestinal symptoms as adults.

There’s no way to prevent pyloric stenosis. If you know pyloric stenosis runs in your family, make sure to tell your baby’s healthcare provider. Their provider can be on the lookout for any signs or symptoms of the condition.

Knowing the signs and symptoms of pyloric stenosis means you can get help as soon as possible. Getting treatment early helps prevent problems such as malnourishment and dehydration.

When you go home from the hospital:

Bring your baby back to their provider seven to 10 days after surgery. Their provider will examine the surgical area and see how your baby is recovering.

Your baby can go back to all regular activities. They can continue to have tummy time, as well.

Some normal swelling around the incision site is normal. But call your baby’s provider if they have:

If your baby has signs of pyloric stenosis, you may have several questions for their provider, including:

A little spit-up is normal for babies. But if your infant is forcefully vomiting after many or all of their feedings, they may have pyloric stenosis. As soon as you notice signs of this condition, contact your baby’s healthcare provider. The sooner they receive a diagnosis and treatment, the better. Delayed treatment can lead to dehydration and undernourishment. The good news is, pyloric stenosis is treatable with surgery, and hopefully, your baby will be healthy and thriving soon.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have issues with your digestive system, you need a team of experts you can trust. Our gastroenterology specialists at Cleveland Clinic can help.