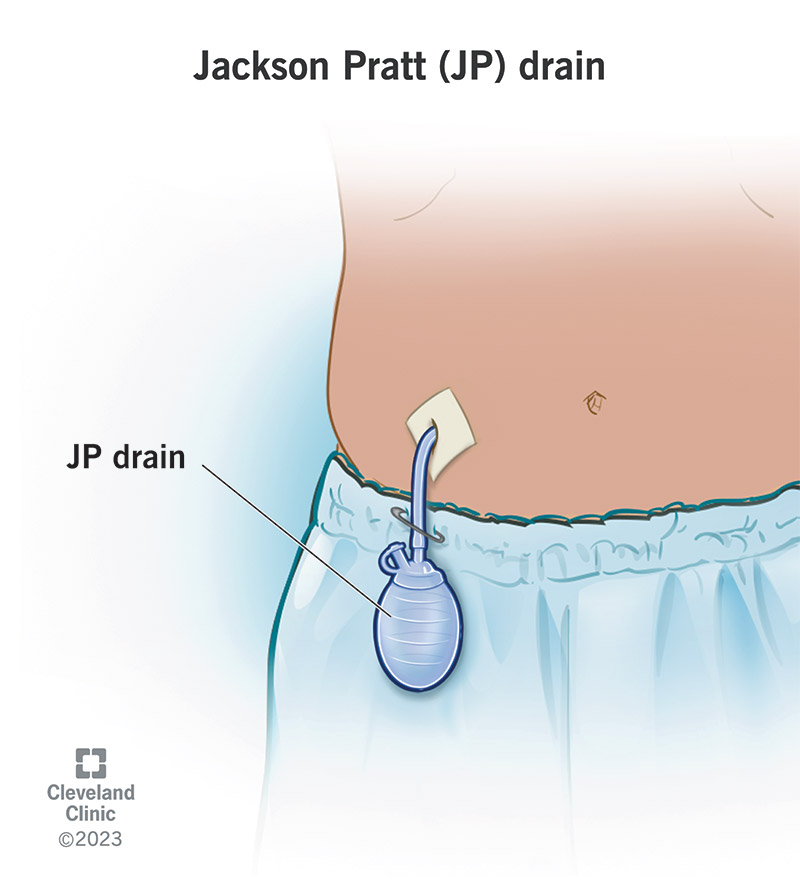

A Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain is a surgical suction drain that gently draws fluid from a wound to help you recover after surgery. To use one, you’ll need to regularly empty a collection bulb that catches the fluid draining from your wound. The bulb pulls the fluid out when it’s squeezed. It can speed up your healing time and reduce your risk of an infection.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/21104-jackson-pratt-drain)

A Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain is a thin, flexible tube with a bulb on the end that drains fluid away from your wound after surgery. After surgery, wounds ooze and shed cells and fluids, like blood and lymphatic fluid (lymph). A JP drain moves the fluid from your wound to the bulb outside your body. Removing the fluid helps you heal faster. It may reduce your risk of an infection if you care for it (and your wound) properly.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A JP drain uses suction to gradually draw fluid from your wound. It has three basic parts:

In technical terms, a JP drain is a closed, active drain system that uses negative pressure to move fluids. It sounds complex, but it’s as simple as this: A squeezed bulb creates pressure that pulls liquid downward from the wound, through the tubing, to the collection bulb.

You’ll need to empty the bulb when it’s about halfway full. Then, you’ll need to squeeze it again to ensure it’s compressed. JP drains are usually compressed to allow the drain to suction. Although it’s rare, some JP drains rely on gravity to drain. (Your surgical team will specify.)

JP drains are the most common type of surgical drains. Surgeons use them to drain fluid after several procedures, like:

Advertisement

JP drains hold less drainage than the other type of closed suction drain, a hemovac drain. The amount of fluid a JP drain can hold depends on the specific model. Generally, it holds from 25 to 50 milliliters (mL) at a time.

Caring for your drain involves emptying it and keeping it compressed, so it continually drains. You should log information about your drainage. A healthcare provider may do this for you in the hospital. They’ll teach you how to do it yourself if you go home with a drain.

You should also clean your wound and change the dressing according to your provider’s instructions.

It’s a good idea to attach the bulb to your clothes so that it doesn’t accidentally get pulled out.

Have the materials on hand you’ll need to empty your drain, including a clean towel or two, an alcohol wipe, gauze and a measuring container. Your provider will send you home with the measuring container.

Advertisement

Repeat the procedure if you have more than one drain. For example, you may need two JP drains after a mastectomy.

Jot down information about your drainage, including what time you emptied your drain, how much drainage there was and what it looked like. These details let your provider know how you’re healing.

If you’re healing, your drainage should decrease daily. Drainage from a wound changes color as it heals. Look for these color changes that let you know you’re healing.

The drainage can also alert your provider of complications, like an infection. For example, drainage that begins to lighten but then returns to dark red can signal that you’re bleeding. Drainage that’s milky white or smelly is a sign of infection.

Follow your provider’s guidance on when and how often you should change your dressing. They’ll teach you how to do it. It’s a good idea to assemble all materials you’ll need beforehand, which may include clean towels, a piece of gauze with a slit halfway down the middle, surgical tape and wound cleanser.

Advertisement

The collection bulb has a loop where you can insert a safety pin to attach it to your clothing, like a shirt or gown. Don’t pin the drain to your pants or belt loops. It’s easy to forget they’re there, and you may accidentally pull them out.

You should empty the drain as often as possible so that the bulb stays compressed. In general, you’ll need to do this every four to six hours the first few days until the amount decreases.

JP drain removal requires a visit to your healthcare provider. Keep the drain in place until your healthcare provider tells you it’s time to remove it. Usually, they don’t stay in for more than two weeks, but this depends on your unique case.

Ask your healthcare provider what to expect before you leave the hospital.

Contact your provider immediately if you notice signs of an infection, including:

Advertisement

Call your healthcare provider if your drain comes loose or is no longer draining fluid. They may need to secure it or ensure it’s airtight. Contact your provider if the tube becomes dislodged or stops holding suction and fills with air. Look for these signs:

Sometimes, after providers remove JP drains, fluid collects and swells at the surgical site (wound). This fluid is called a seroma. This isn’t an emergency, but you should alert your provider.

It’s a closed drain. Think of the JP drain as a closed system that relies on air pressure changes within the system to pull fluid from a wound. Instead of draining outside your body and onto dressing (as with open drains, like the penrose drain), the fluid collects in a bulb that pulls fluid out when it’s compressed.

A JP drain can feel like a weird new extension of your body while you’re recovering. In a way, it is. JP drains act like an added body system that helps you heal by drawing fluid out. Getting used to a JP drain can feel awkward at first, but don’t be intimidated. A JP drain can help ease your recovery while reducing your risk of complications.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Sometimes you have surgery planned. Other times, it’s an emergency. No matter how you end up in the OR, Cleveland Clinic’s general surgery team is here for you.