Top Moments

1920s

The Dream Takes Shape

When Cleveland Clinic opened its doors on Feb. 28, 1921, it was a new kind of medical center: a not-for-profit group practice, dedicated to patient care and enhanced by research and education. One of the principal motivations for founding Cleveland Clinic, according to Dr. Crile, was that advances in medicine had made it impossible for the individual physician to undertake complex problems alone.

Cleveland Clinic flourished from 1921-1928. A 140-bed hospital, laboratories and a pioneering diabetes treatment unit were built. Patients and visitors included William Randolph Hearst, Charles Lindbergh and government officials from the United States and abroad.

On May 15, 1929, disaster struck. Volatile nitrocellulose X-ray films stored in the basement of the outpatient clinic combusted, sending a cloud of poisonous gas throughout the building. Heroic and self-sacrificing actions by caregivers and first responders saved lives; however, 124 patients, visitors and caregivers died from gas inhalation.

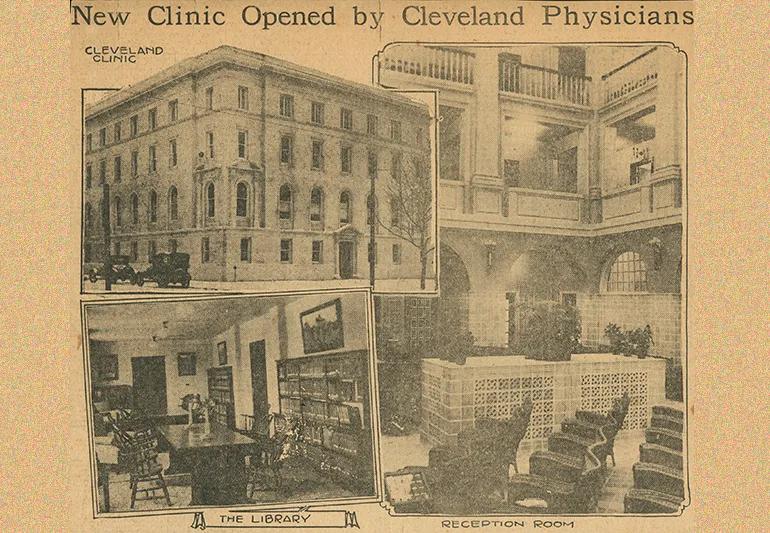

Construction begins

In February of 1920, ground is broken on the original Clinic building. The topping out "flag-raising" ceremony is held on July 3, 1920.

Opening ceremony

George Crile Sr., MD, Frank Bunts, MD, William Lower, MD, and John Phillips, MD, open Cleveland Clinic as a not-for-profit multispecialty group care organization to provide patient care, research and education. William Mayo, MD, delivers the keynote address at the dedication of the new offices on February 26, 1921.

Cleveland Clinic opens its doors on February 28, 1921. Cleveland Clinic starts as a single building on Euclid Avenue at East 93rd Street.

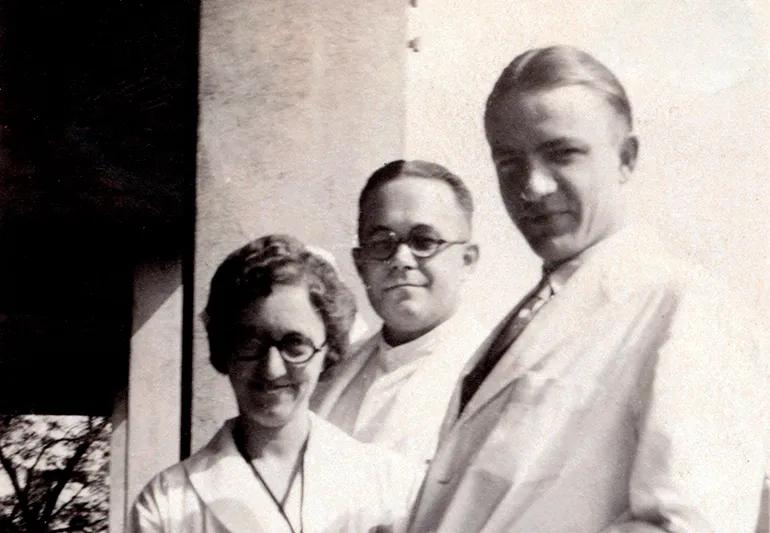

Cleveland Clinic welcomes its first residents (then called fellows) in the 1920s, including W.O. Johnson, MD, (center) the first surgical resident, shown here with resident Arvid Krueger, MD, (right) and an unidentified nurse (in cap).

When four-year-old orphan Madeleine Bebout fell into a diabetic coma in 1922, Cleveland Clinic's Henry John, MD, was able to save her life using a new discovery: insulin. During her recovery and treatment, Cleveland Clinic became more than a medical provider to Madeleine; she lived for several years in the Diabetic Home on 93rd Street.

Cleveland Clinic Hospital opens

In June 1924, Cleveland Clinic Hospital opens.

Otto Glasser, MD, invented a way of accurately measuring the radiation doses being given to patients during what was then called Roentgen ray therapy (radiotherapy for cancer). The groundbreaking device was called a dosimeter.

Maria Telkes, PhD, joins Cleveland Clinic to perform cell research. She was among the first women employed at Cleveland Clinic as a physician or scientist.

Cleveland Clinic founder Frank E Bunts, MD, dies on November 28, 1928. The Bunts Education Institute was named in his honor in 1935.

Disaster strikes

On May 15, 1929, volatile nitrocellulose X-ray films stored in the basement of the outpatient clinic combusted, sending a cloud of poisonous gas throughout the building. Heroic and self-sacrificing actions by caregivers and first responders save lives, but 123 patients, visitors and caregivers die from gas inhalation. Many nurses sacrificed themselves to save others. Among the dead was John Phillips, MD, one of Cleveland Clinic’s founders. The incident remains the worst hospital disaster in American history and led to revised safety standards for the storage of X-ray films nationwide. Just five days after the disaster, Cleveland Clinic resumed operations in temporary quarters, with over 300 patients registering right away. The explosion had rendered the building unusable, but in an example of community generosity, the headmistress of Laurel School donated a former dormitory for Cleveland Clinic’s use. Operations remained there until September, when Cleveland Clinic moved out of the former Laurel School building and into the new space.

Lillian Grundies, RN, was Cleveland Clinic’s first head nurse and a valiant presence during the 1929 disaster. Able to escape the building by ladder, she worked all through the night and the following day saving lives. One life she couldn’t save was that of her long-time colleague William Brownlow, Cleveland Clinic’s first photographer and medical illustrator. He passed away with Ms. Grundies at his side, late in the evening.