Calling Evan Culp an active kid is an understatement. “Running, jumping, playing outside, four-wheeling, swimming – he’s always doing something,” says mom Felisha Culp, of her effervescent 10-year-old son.

However, in late July 2021, Evan began vomiting after every meal. His local pediatrician suspected gastritis and told Felisha it would likely clear up in a few days. Unfortunately, it didn’t, and Felisha rushed her son to a local emergency department.

After Evan was transferred by ambulance from his hometown in Lorain, Ohio, to Cleveland Clinic Children’s, the family learned of his shocking diagnosis – end-stage heart failure . It was most likely caused by a genetic condition called left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC). Evan’s health was declining rapidly.

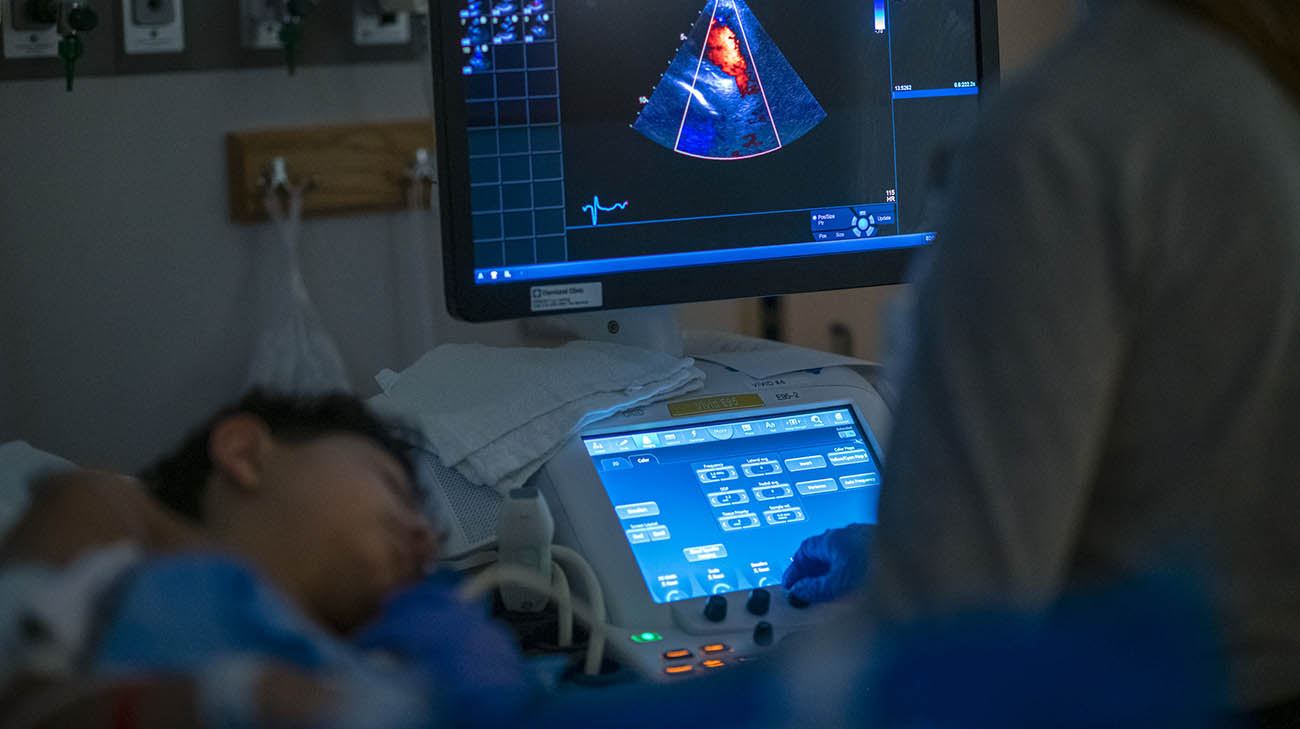

Evan undergoing an echocardiogram at Cleveland Clinic Children's. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

“Until he began throwing up, there was no evidence anything was wrong with him,” says Felisha, whose own congestive heart disorder emerged when she gave birth to Evan. “It was completely out of left field. Never in my wildest dreams did I think he had this problem.”

Upon arrival at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, a team led by pediatric cardiologists Gerard J. Boyle, MD, and Shahnawaz Amdani, MD, quickly set about the task of stabilizing Evan and trying to reverse the effects of the disease.

“He came in very sick, and it was quite obvious his heart was the issue,” explains Dr. Boyle, who is Medical Director of Pediatric Heart Failure and Transplant Services. “He was having trouble breathing. He was deeply fatigued, and an echocardiogram revealed his cardiac output was very poor.”

Doctors diagnosed Evan with end-stage heart failure, likely caused by a genetic condition. (Courtesy: Felisha Culp)

Dr. Boyle calls LVNC, a “very insidious disease.” The heart muscle disorder occurs when the heart’s blood-pumping left ventricle, which is normally smooth and compact, grows much larger in size and forms a jagged surface with bumps and crevices. This impedes blood flow, and in some severe cases like Evan’s, can result in heart failure or stroke .

To treat Evan, the team first tried administering intravenous (IV) medications to “kick start the heart,” adds Dr. Boyle. While that provided some relief, and Evan was able to go home for about 10 days, its effects were temporary.

“It was evident Evan’s health was still failing. His color was off, and he didn’t want to get out of bed or eat,” recalls Dr. Boyle. “We knew then we were not going to win this battle with medication. He would need a heart transplant.”

Evan recovering at Cleveland Clinic Children's after undergoing a heart transplant. (Courtesy: Felisha Culp)

Admitted back to the hospital, Evan would not leave until a donor heart was found. Felisha and her husband, Edwin, rarely left Evan’s side. She remembers Evan being confused and upset by the sudden onset of his condition, “In a matter of days, he went from being a healthy, normal kid to being hooked up to machines and not being able to leave the hospital.” On some days, Evan was able to get out of bed and play with his toy cars. But most of the time, he was too weak and sick to do much of anything.

As his condition worsened, Drs. Boyle and Amdani collaborated with their colleagues in adult cardiology to determine if a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) could be used in Evan to keep his body healthy enough to undergo a transplant. A mechanical pump, an LVAD is implanted in patients with heart failure to help the left ventricle efficiently pump blood out to the aorta and the rest of the body.

They settled on a type of LVAD they had never used before in a patient so young. Its hockey-puck size would fit well into Evan’s chest, and would likely allow him to be more functional than he would be compared to other LVADs that usually require almost non-stop bedrest.

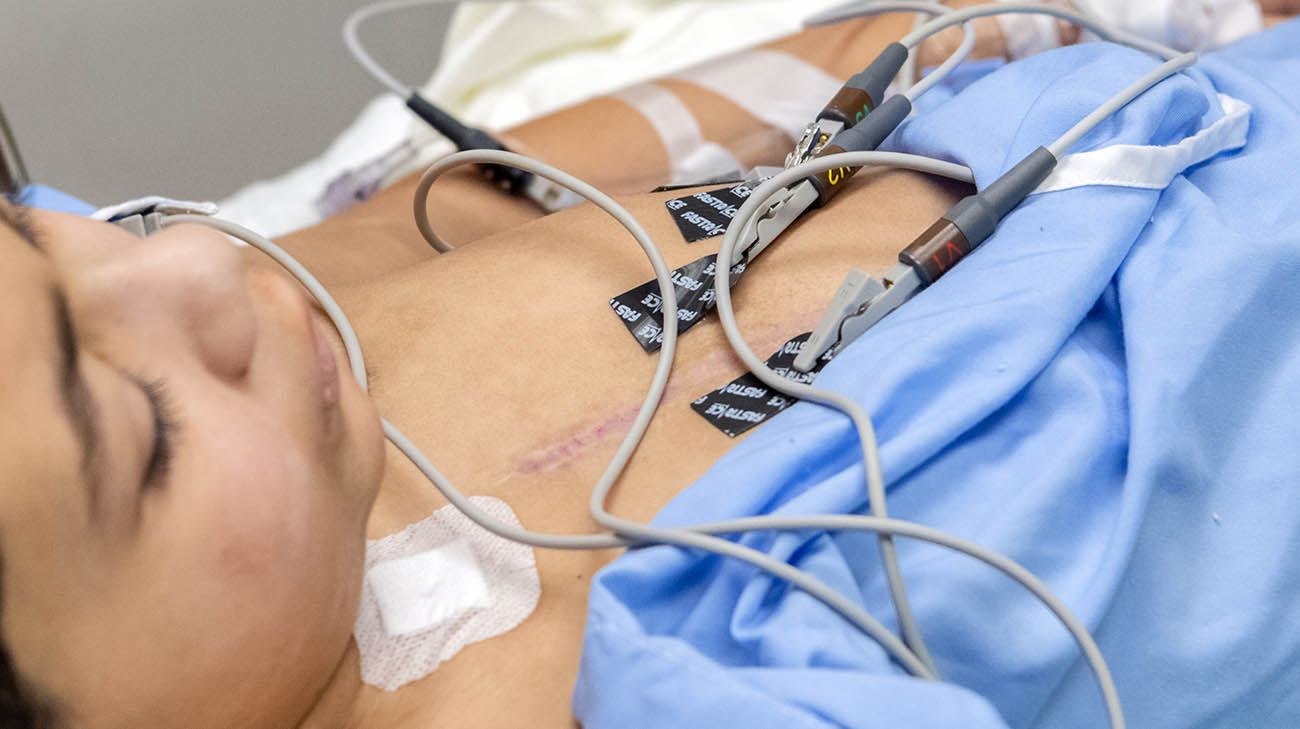

Evan undergoing follow-up testing at Cleveland Clinic Children's. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

“It was an enormous team effort, and the procedure went off exceptionally well,” Dr. Boyle adds. “Evan recovered very quickly.”

Fortunately, Evan wouldn’t need the LVAD for very long. Less than 10 days later, Felisha got the call she had been praying for – a donor heart had been found that was a perfect match for Evan. She remembers waiting through his 9-hour transplant surgery as one of the most difficult times in her life. When she was able to see her son in recovery, just after midnight, despite being intubated and on pain medications, he was awake and smiled at her.

Felisha says, “I understand the true meaning of miracles and blessings. I am thankful for all who worked so hard for Evan.” Within days, Evan was playing video games, and his appetite returned. “We couldn’t feed him enough,” says Dr. Boyle. “He looked and felt much better. His kidney, liver and other organs really started to recover.”

Evan's family is grateful to have him home and back to being his energetic, carefree self. (Courtesy: Felisha Culp)

Less than three weeks later, Evan went home. While the coronavirus pandemic has limited his ability to spend much time with other kids in recent months, Evan will return to in-person classes at school in March 2022. Dr. Boyle says there are basically no limitations on what activities he can engage in.

“I’m just grateful he’s home and doing so well,” says Felisha. “Evan is back!”

Related Institutes: Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family), Cleveland Clinic Children's