Young, healthy and in excellent physical shape, Cleveland State University volleyball player Marissa Durand expected to bounce back quickly when she contracted COVID-19 in August 2020, just after returning to campus for her sophomore year.

“I remember thinking this is something that isn’t supposed to affect young people too badly,” says 19-year-old Marissa, who due to the lingering effects of the disease is not currently playing volleyball. “I was super careful, more than any of my friends, about trying to stay protected, and I still caught COVID. Obviously, I’m even more careful now. I don’t even want to think what would happen if I got it again.”

Ten months after being infected with the coronavirus, Marissa is slowly, painstakingly striving to recover. She is among those patients who have been debilitated by so-called “long COVID,” a collection of mild to severe symptoms known more formally as post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC).

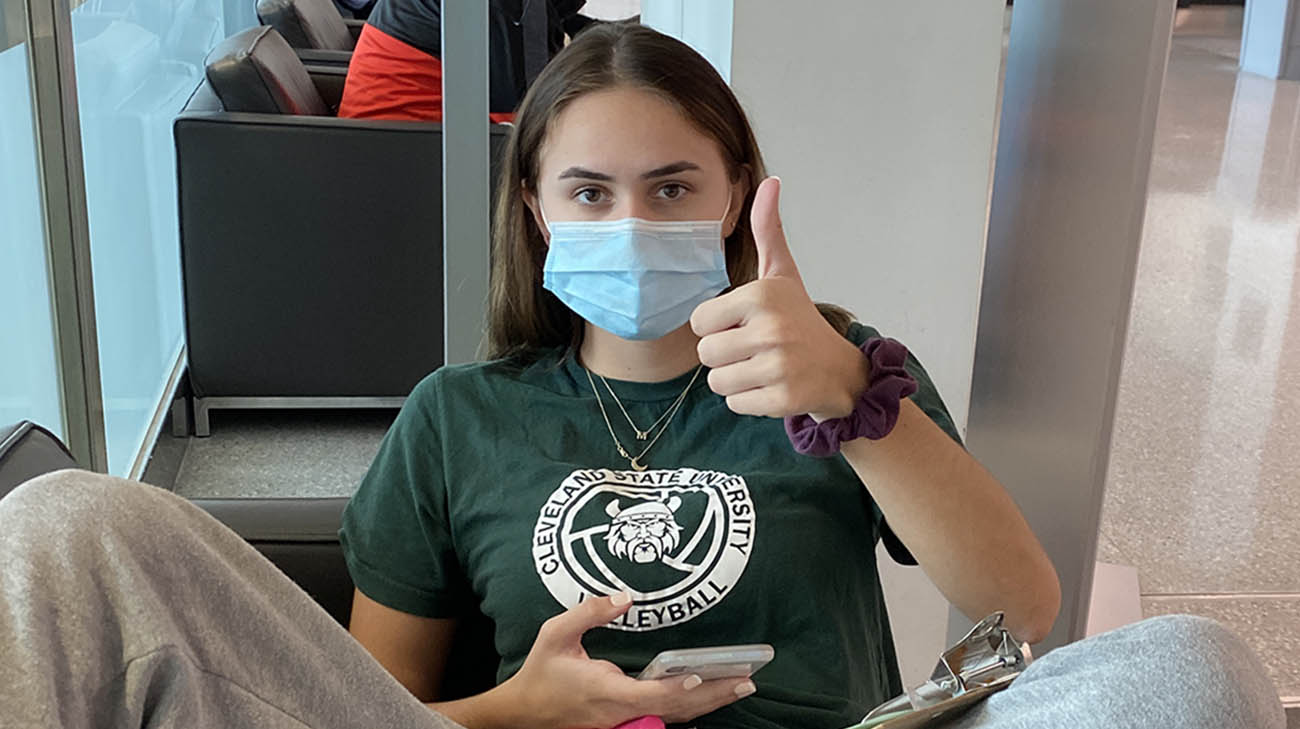

Marissa has tried to maintain a positive attitude throughout her journey. She hopes her story will help others. (Courtesy: Marissa Durand)

In Marissa’s case, the most consequential aspect of her PASC has been a consistently rapid heartbeat of up to 190 beats per minute that can manifest just by standing up or walking short distances. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) affects the autonomic nervous system, which automatically controls and regulates vital bodily functions, including blood flow.

“You think an athlete is strong and can do just about anything, physically,” says Marissa, who with medication and physical rehabilitation can once again perform some normal activities, such as walking up to 1.5 miles daily. “But when your heart is racing, it means nothing. Even standing in line at the pharmacy for five minutes, to get my medication, I would almost pass out.”

While POTS can be effectively treated in a number of ways, none has made a dramatic improvement for Marissa, a confounding situation for her and her Cleveland Clinic cardiologist Tamanna Singh, MD. “I tell Marissa she was my patient zero with respect to COVID and POTS, and she has been very accommodating throughout her treatment, because she’s so interested in helping others like her. But it’s been really frustrating, as her provider, that she continues to struggle.”

During the first few months Marissa battled with COVID and POTS, she remained on campus, but could rarely leave her room. She registered with the university’s office of disability, which enabled her to do things like retake timed tests when she became too nauseous and lightheaded to complete written exams.

“Some days, just waking up and opening my eyes would cause a severe headache,” Marissa recalls. “It became a struggle just to get out of bed. And when I did my heart would start racing, and I’d have to lay back down again.”

Once she returned home to Michigan midway through the fall 2020 semester, where her parents have been able to assist her, Marissa has slowly, steadily noticed some improvement. Just before Christmas, she returned to Cleveland to get an infusion of intravenous immune globulen (IVIG), which has been effective on some POTS patients. Unfortunately, it did not work for Marissa.

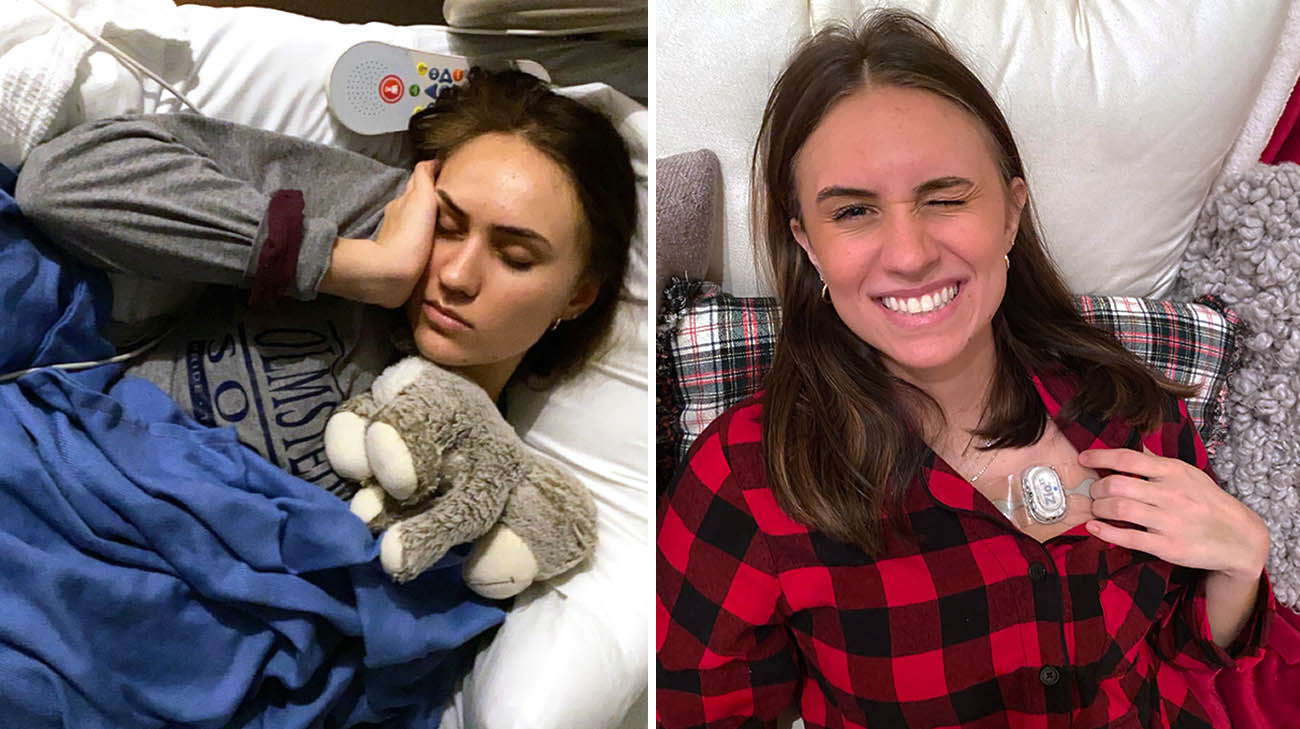

Marissa underwent IVIG infusion in an attempt to treat her POTS (left). Afterwards her care team monitored her heart (right). (Courtesy: Marissa Durand)

What has worked are other medications prescribed by Dr. Singh, after consultations with several of her colleagues, as well as relatively gentle forms of physical therapy, such as sitting down and slowly peddling a one-wheel exerciser. She has since progressed to standalone bicycles and walking.

“We’ve encouraged Marissa to exercise as much as she can tolerate, which is helping to improve her heart rate variability,” notes Dr. Singh. “I’m happy to see minimal progress, but it’s unfortunately a very, very slow process.”

While excited by the progress she is making, Marissa is frequently reminded of how careful she must be. Just last week, while taking a stroll through the neighborhood near her home in Michigan, she decided to trot for around a hundred yards.

“When I got back home, I just laid down on the floor because I was so exhausted. I was hungry but couldn’t even get up to eat,” she recalls. “It was about nine hours before I recovered.”

In fall 2021, Marissa will return to campus for her junior year at Cleveland State University, majoring in biology with a minor in marketing. However, her volleyball career is indefinitely on hold. Marissa has handled this setback stoically and with determination.

Marissa has been slowly adapting to no longer playing volleyball. She hopes to continue making progress so she can get back to a normal life. (Courtesy: Marissa Durand)

“It’s a bummer, but I haven’t played in a year now and I’ve slowly been adapting to it. At this point, the biggest thing I’m looking forward to is being able to live on campus, go places with my friends and just be able to walk to class. It’s time to get back to a normal life.”

While COVID-19 vaccines were not available when Marissa became infected, she does encourage all eligible individuals – especially younger people -- to get it as soon as they can.

“I know some people worry about getting sick from the vaccine, but I would much rather be sick for a day or two than have COVID. It’s been almost a year, and I still haven’t returned to a normal life,” she says. “I think the vaccine is definitely worth it. Looking at what COVID and POTS have done to me, it’s better to be safe than sorry.”

Related Institutes: Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family), Respiratory Institute