When Thelma Mae Crowe Bumpus died in 2003, at age 97, she carried a family secret: Breast cancer.

Thelma Mae had been diagnosed and treated for the disease, and so have many of her descendants. That includes her great-granddaughter Tamara Bumpus, a nurse practitioner in Toledo who treats homeless people and others who have limited access to medical services.

But Tamara, who discovered a lump on her right breast in 2016, is the first to readily talk about the disease that has plagued so many women on her father’s side of the family.

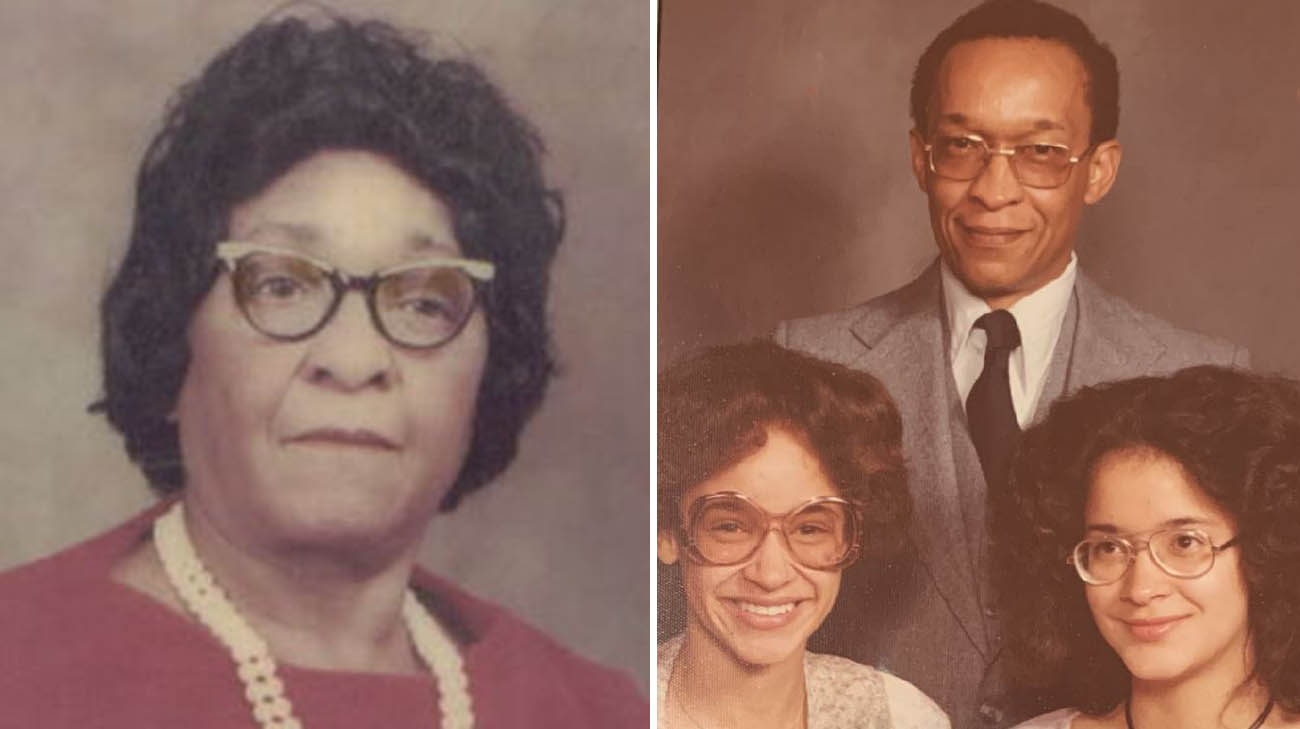

(left) Tamara's grandmother, Thelma Mae Crowe Bumpus. (right) Tamara with her father and sister, Monica. (Courtesy: Tamara Bumpus)

“All of (Thelma Mae’s) female children had breast cancer, and so did all of their daughters, except for one who refused to be tested,” says Tamara. “And all of her sons have at least one daughter with breast cancer, even though none of us have a gene we can point to as the cause.”

Thanks to Tamara the silence is stopping. “Nobody ever wants to talk about the ‘Big C,’ but if we don’t, our loved ones may not know they could be at risk.”

Tamara was diagnosed “quite by accident,” she says. It was discovered while undergoing testing, at a local hospital close to her hometown, prior to an elective surgical procedure. A mammogram detected the lump, and a biopsy confirmed the devastating news it was cancer. It was only through a subsequent genetic test Tamara learned about the prevalence of the disease in her family (although a specific gene has not been found as the culprit in her family tree).

Tamara went from taking care of patients as a nurse, to becoming a patient, after being diagnosed with breast cancer. (Courtesy: Tamara Bumpus)

“The geneticist said I had a 60% chance of discovering cancer in my other breast during my lifetime,” Tamara recalls. “That’s when I decided to have prophylactic mastectomies of both breasts.” The procedure removes the breast tissue as a preventative measure, even if no cancer has been discovered.

According to Tamara’s Cleveland Clinic surgeon Risal Djohan, MD, a specialist in breast reconstruction, increasing numbers of women are choosing to undergo a prophylactic mastectomy.

“Whether it’s because they have a strong family history, along with the discovery of a hereditary breast cancer gene, or very dense breast tissue that makes it very difficult to detect cancer, it is an option that can benefit them in the long run,” says Dr. Djohan, who typically works in tandem with surgeons to conduct the procedure. “They don’t have to worry about chemotherapy, radiation or other invasive procedures later on, if they were to get breast cancer.”

Tamara (center) with her sister, Monica, (bottom left), and her longest living relative, Ann V. Brown. (bottom right). (Courtesy: Tamara Bumpus)

A deciding factor for Tamara in making that choice was Dr. Djohan’s proficiency in a breast reconstruction surgical technique called deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) free flap. Instead of reconstructing the breast by inserting an artificial implant, DIEP involves removing abdominal fat, skin, fatty tissue and blood vessels from the patient’s lower abdomen and transplanting them into the breast area.

“Luckily, I had enough body fat for it to happen,” says Tamara with a laugh. “But it was important to me to retain sensation in my breasts, something you don’t get with implants. My breasts look almost exactly like they did before the mastectomies, and I still feel womanly. That’s an important part of the human experience.”

Tamara’s cancer removal and reconstructive surgeries were successful, and so have been her efforts to talk about breast cancer with her fellow family members, including her 17-year-old daughter, Madeline.

Tamara hopes knowing her family health history will also benefit her daughter, Madeline. (Courtesy: Tamara Bumpus)

“Now, among my own family and anyone else who will listen, I talk about it,” says Tamara, who has signed a release form authorizing anyone in her family to get access to her genetic testing results. “By letting others know about our family history of cancer, they can let their doctors know that they’re at risk for it, too, and take steps at getting screenings done earlier.”

Dr. Djohan is impressed by her willingness to talk about her family’s proclivity for getting breast cancer. “Tamara is a very good patient advocate,” he says. “She wants people to know about it and take the right steps to look out for cancer.”

Related Institutes: Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute , Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center