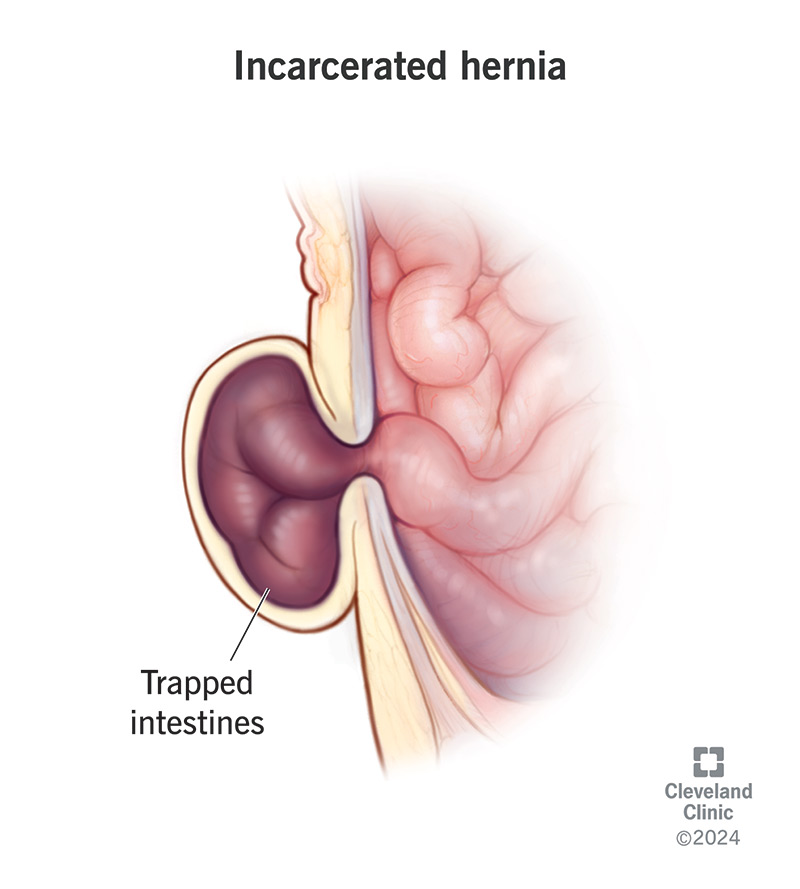

An incarcerated hernia is a hernia that’s stuck. Pressure from your abdominal muscles keep it from moving back into your abdomen. An incarcerated hernia can cause a lump or bulge in your lower abdomen or groin. Other symptoms are severe pain, nausea and vomiting. Treatment may be surgery to move the hernia’s content back into your abdomen.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/incarcerated-hernia.jpg)

An incarcerated hernia happens when muscles in your abdomen trap (incarcerate) a hernia. Unlike most hernias, an incarcerated hernia doesn’t move back into your abdomen on its own or when you push on it.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Any type of hernia can get stuck in your abdominal muscles. But inguinal (groin) and femoral (upper thigh) hernias are more likely to become incarcerated.

Incarcerated hernias can be sudden and severe (acute). Or you may have it for a while and not notice symptoms right away (chronic).

An incarcerated hernia creates a noticeable lump or bulge in your abdomen or groin that doesn’t go away. You may develop other symptoms like:

An incarcerated hernia may keep you from pooping. That can happen if pressure on the trapped hernia blocks your intestine (obstructed bowel) so poop can’t move through your intestine.

You may develop an incarcerated hernia if there’s an unusual amount of pressure on your abdominal muscles. The extra pressure may cause your abdominal muscles to press harder on the hernia so that it gets stuck. You may put extra pressure on your abdominal muscles if you lift heavy objects or have a chronic cough. Other issues that may lead to an incarcerated hernia include:

Advertisement

You can also develop an incarcerated hernia if there’s scar tissue in your abdominal muscles from a previous hernia surgery. In that case, you have a new hernia that’s pushed through the surgery site. Scar tissue from the previous surgery may keep the new hernia from moving back into your abdomen.

A strangulated hernia is the most serious complication. A strangulated hernia cuts off blood flow to the tissue, organ or intestine in the hernia. This condition is a medical emergency.

A healthcare provider will do a physical examination. They’ll ask about your symptoms, like whether you’re able to poop. They may do a computed tomography (CT) scan to look at the hernia’s contents. They may also press on the lump or bulge to move the hernia. If it doesn’t move, your provider considers the hernia to be an incarcerated hernia.

An incarcerated hernia is a surgical emergency and requires hernia repair surgery.

Your recovery time depends on the extent of surgery. In general, you should be able to resume your usual activities within a few days. Your surgeon may set limits on how much weight you should lift. But everyone’s situation is different. Ask your surgeon what you can expect and what you can do to support your recovery.

Talk to your healthcare provider if you think you may have a hernia. They’ll examine the bump or lump that the hernia can cause to confirm you have an incarcerated hernia.

You may want to ask your healthcare provider the following questions:

There’s a lump or bulge in your lower abdomen or groin. It may not hurt. But it doesn’t go away. That kind of change in your body is something you should discuss with a healthcare provider. Tests may show you have an incarcerated hernia. The hernia won’t go away without treatment. And without treatment, an incarcerated hernia may cause more serious medical issues. Talking to a provider is the first step toward taking care of a worrisome lump or bulge.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Hernias can be painful – Cleveland Clinic’s experts can help. We are leaders in minimally invasive hernia repair, and abdominal wall reconstruction.