Twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) is a pregnancy complication that involves imbalanced blood flow between identical twins. The imbalance deprives one twin of the nutrients it needs while providing an excess of nutrients to the other twin. Treatment depends on how far you are in pregnancy and how severe the condition is.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22985-twin-to-twin-transfusion-syndrome)

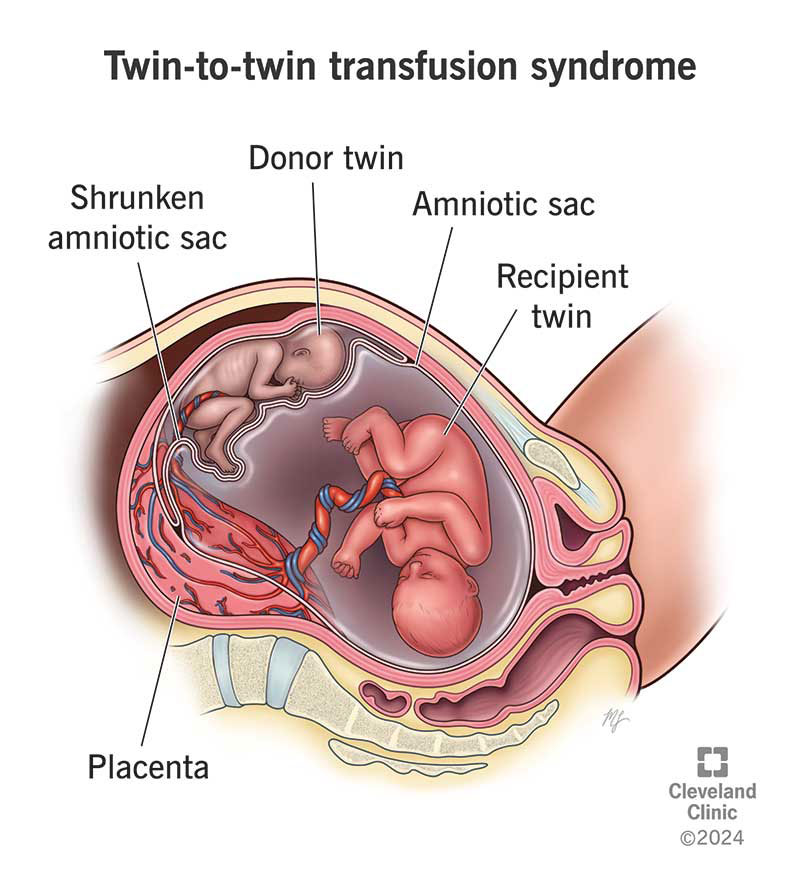

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) is a rare, serious condition in pregnancies involving identical twins who share one placenta (also called monochorionic twins). While most identical twins share blood and nutrients from the same placenta equally, twins affected by TTTS don’t. Instead, one twin (the donor twin) receives less blood supply than the other twin (the recipient twin). This means the donor twin has less blood volume, but the recipient twin has more blood volume. This blood flow imbalance can cause TTTS.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome requires close monitoring from a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist. Early detection, monitoring and treatment are crucial for improving the outcome for both twins.

The donor twin receives less blood flow from the placenta compared to the recipient twin. As a result, the donor twin has less blood volume. This can lead to slower growth and decreased amniotic fluid volume. The donor twin urinates less. Since amniotic fluid is made up mostly of urine (pee), the amniotic sac can shrink or even disappear. When the amniotic fluid is low, the membrane or sac that the donor fetus is in can collapse around it. A shrinking amniotic sac is concerning because it can affect the movement of the fetus and can compress the umbilical cord.

The recipient twin receives too much blood volume from the placenta. The excess blood volume can put a strain on the recipient twin’s heart, leading to heart failure. While the donor twin’s body can be undernourished, the recipient twin’s body is overworked. The recipient fetus has to process too much blood volume and makes more urine than is typical, leading to an amniotic sac that’s much larger.

Twin-twin transfusion syndrome affects women who are pregnant with identical twins that share one placenta (monochorionic twins). In most cases of TTTS, the twins have two separate amniotic sacs (diamniotic). These types of twins are called monochorionic diamniotic.

Advertisement

TTTS can also happen when twins share both a placenta (monochorionic) and an amniotic sac (monoamniotic), but these types of twins are less common.

TTTS typically develops as early as 16 weeks of pregnancy, but it can develop at any time.

Approximately 15% of identical twin (monochorionic) pregnancies will develop TTTS.

TTTS doesn’t cause symptoms most of the time. For those who do experience symptoms, they could include:

In typical pregnancies involving twins with one placenta (monochorionic), both fetuses equally share the same blood volume from the placenta. With TTTS, the blood vessels connect in the placenta in a way that allows blood volume to be distributed unequally, with the recipient twin getting more and the donor twin getting less.

How the placenta develops is beyond your control. TTTS happens by chance, and it’s not because of something you did or didn’t do. There’s no way to prevent twin-twin transfusion syndrome.

There isn’t a genetic or hereditary component to TTTS. It’s random but can only happen in identical twin pregnancies where both fetuses share a placenta (monochorionic).

When left untreated or in severe cases that occur early in pregnancy, TTTS is associated with high morbidity and mortality. It’s essential that you receive treatment or close monitoring from an MFM specialist or fetal care center. Even with early treatment, there’s a risk of pregnancy loss.

Other complications of TTTS, in general, are:

Your pregnancy care provider will diagnose twin-twin transfusion syndrome with an ultrasound. The first thing your provider will see on an ultrasound is a twin pregnancy with fetuses sharing one placenta.

If your pregnancy care provider suspects TTTS, they’ll refer you to a specialist in maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) for further testing. From there, the MFM will notice one or more of the following on ultrasound:

In some cases, a fetal MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and fetal echocardiography (echo) may be necessary.

Your pregnancy care team will monitor you very closely for the rest of your pregnancy. You’ll need frequent ultrasounds to assess the twins’ health.

Your provider will also assess your health. Sometimes, the increased amniotic fluid from the recipient can cause your uterus to get bigger and your cervix to weaken. These changes can lead to preterm labor and early delivery.

Advertisement

Part of the ultrasound evaluation involves assessing the stage of TTTS or how severe it is. This allows your physician to follow the progression so that they can recommend the best treatment options.

There are five stages of TTTS:

Stage 1 TTTS may only need monitoring or close observation. Progression can happen very quickly (if it does happen). Once TTTS progresses to stage 2, fetal surgery is usually offered if you’re less than 26 weeks.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_0pcvbxad/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Learn more about what happens during fetoscopic laser surgery for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome.

Treatment depends on how far along you are in your pregnancy and what stage of TTTS you have:

Advertisement

Your healthcare team can help you determine which treatment is the best option. They’ll answer any questions you have and discuss the risks, benefits and alternatives to each of the procedures with you.

Your healthcare provider will monitor your pregnancy closely with the MFM specialist. You’ll need frequent ultrasounds (often weekly or semiweekly) and, possibly, a fetal echocardiogram during your pregnancy. Your care team will offer both medical and emotional support throughout your pregnancy.

The outcome depends on the gestational age you receive a diagnosis and how serious it is (stage). Advances in medicine make it possible, with close monitoring and quick treatment, for both twins to have a better chance of surviving. You should discuss expectations and possible outcomes with your provider so that you understand what TTTS means for your pregnancy and your twins. Most surviving twins will need to spend some time in the NICU after they’re born to give them the start they need.

TTTS can be a highly emotional and stressful experience. Make sure you take care of yourself and lean on your healthcare team, partner(s) and friends for support.

The survival rate depends on how severe the TTTS is, when you receive a diagnosis and if you get treatment. Receiving appropriate treatment makes all the difference when it comes to the survival rates with TTTS:

Advertisement

Talk with your care team about the prognosis (outlook) for your twins, as many factors play a role in survival.

Some questions you may want to ask include:

A daisy baby is another name for babies with TTTS. The Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome Foundation coined the term after its founder planted daisy seeds with her surviving twin son in their backyard. The daisy field is a symbol of hope that all babies affected by TTTS will survive.

Receiving a diagnosis of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome can be scary. It’s common to experience fear and anxiety about what comes next for both you and your twins. Speak with your provider about treatment options that work best based on your unique situation. Reach out to friends and family members for support as you progress through your pregnancy. Joining support groups for families who’ve experienced TTTS can provide additional support to help you along your journey.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Worried about your high-risk pregnancy? Want the best maternal and fetal health care? Look no further than Cleveland Clinic. We’re here for all your needs.