Background

Neal Mehta, MD

William Carey, MD

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains one of the most important clinical and public health problems facing modern medicine. In 2015, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that 170 million people worldwide are living with chronic HCV infection and almost 20,000 died from HCV–related liver disease in 2014. Hepatitis C–related deaths in 2013 surpassed the total combined number of deaths from 60 other infectious diseases reported to the CDC, including HIV, tuberculosis, and pneumococcal disease.

In the United States, an estimated 1% of the population is infected. As recently as 2017 an estimated 44,700 new cases occurred. Those between ages 20-39 are most likely to become infected. Injection drug use is the most common mode of acquisition. HCV rate increases are particularly noted in American Indians, Alaskan natives, and non-Hispanic white populations. More information is available. (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-c-screening).

Although 15% to 25% of infected individuals spontaneously clear the virus without any treatment, approximately 75% to 85% will develop chronic HCV infection. The risk of cirrhosis after chronic HCV infection is 20% within 20 years and 30% within 30 years. Cirrhosis–related mortality from HCV ranges from 2% to 5% per year. Finally, in people with HCV cirrhosis, liver cancer occurs in an estimated 3% to 10% per year. Chronic HCV infection is the leading indication for liver transplantation in the U.S.

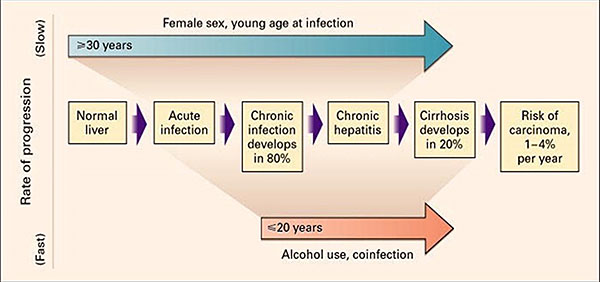

Various epidemiologic risk factors can influence the risk and rate of HCV progression including age at acquisition, male sex, alcohol exposure, genetic factors, coinfection with other viruses, and other comorbidities (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Fortunately, this life–threatening viral infection can now be eradicated in nearly all affected people. It is estimated that by 2025, HCV will be a rare disease. The World Health Organization proposes elimination of HCV world-wide by 2030.

Distinction between HCV as an infection, on the one hand, and a liver disease, on the other, is important. Most people with HCV have little or no visible evidence of liver damage, and if confirmed, management of the underlying infection is all that needs to concern the clinician. Once cured of HCV no additional follow up is needed in individuals without significant hepatic fibrosis. Those with significant liver damage need both antiviral therapy and attention to the potential consequences of a damaged liver

Virology

HCV is a ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus classified in the Flaviviridae family. HCV replicates in the liver and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and it is detectable in serum during acute and chronic infection. The exact mechanism of viral entry into liver cells is not known, but it is associated with several viral and cellular factors. During HCV assembly and release from infected cells, virus particles associate with lipids and circulate in the blood in the form of triglyceride–rich particles. HCV polymerase is an enzyme encoded in the HCV genome that lacks error–correcting mechanisms, leading to a high mutation rate that likely contributes to the virus’ ability to evade the body’s immune system.

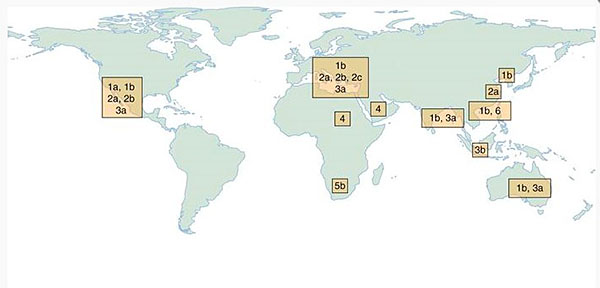

There are six major genotypes of HCV. Genotype does not affect the natural history of the disease. In the U.S., the predominant genotype is G1, constituting approximately 70% of individuals, 16% G2, 12% G3, and smaller proportions with genotypes 4, 5, or 6. Figure 2 indicates the geographic prevalence of HCV genotypes. Currently used antiviral treatments are highly effective against all genotype, although slightly less so against G3.

Figure 2. Geographic prevalence of the 6 major HCV genotypes (G1-G6).

Transmission

In the past, a major route of infection was via blood transfusion; however, effective screening of blood donations for HCV (since 1992) has reduced the risk of transfusion-associated HCV to less than 1 per 2 million units transfused. Currently, the most common route of transmission is related to intravenous drug use. Other modes of transmission include having multiple sexual partners, tattooing, body piercing, and sharing straws during intranasal cocaine use.

Mother–child vertical transmission occurs in approximately 5% to 10% of cases and is more likely to occur in a mother co-infected with HIV. There are no conclusive data to advise against breastfeeding for women with HCV infection. Reports of infection rates after an HCV–contaminated needle–stick injury range from 0% to 10.3%, with an average rate of 0.5%, although not all infections lead to long–term infection.

Transmission to a sexual partner in a monogamous relationship is uncommon with rates as low as 0.07% per year. Accordingly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not suggest any change in sexual practice among monogamous couples.

Screening

Because the presence of hepatitis C is most often asymptomatic, most infected individuals are unaware. This creates an environment for inadvertent spread of disease. Clustering of infected individuals and the age cohort born between 1945 – 1965 led to recommendations of age cohort screening. One–time testing for antibodies to HCV (anti–HCV) by age–cohort was estimated to identify 800,000 more HVC infections. With subsequent treatment, testing by age cohort was estimated to avoid nearly 120,000 HCV–related deaths. Since implementation of age cohort testing, an estimated $1.5 to $1.7 billion dollars has been saved in liver disease–related costs.

The US Preventive Task Force recommends hepatitis C screening for all between 18 -79 year of age. The CDC also recommends wide spread testing (Table 1).

Table 1: Hepatitis C screening Recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)

|

Universal hepatitis C screening |

All pregnant women during each pregnancy |

|

One‑time hepatitis C testing regardless of age or setting prevalence among people with recognized conditions or exposures

Ever injected drugs, shared needles, syringes, other drug preparation equipment Ever received maintenance hemodialysis; or people with persistently abnormal ALT levels |

|

Transfusions or organ transplants, including:

Transfusion of blood or blood components before July 1992 Organ transplant before July 1992 Those notified that they received blood from a donor who later tested positive for HCV infection |

|

Routine periodic testing for people with ongoing risk factors

Hemodialysis |

|

Any person who requests hepatitis C testing |

Signs and Symptoms

Acute HCV infection is uncommonly recognized because it is usually asymptomatic or accompanied by mild flu–like symptoms. Fatigue is the most common symptom. Other complaints include weight loss, muscle or joint pain, irritability, nausea, malaise, anorexia, depression, abdominal discomfort, difficulty concentrating, and jaundice. These symptoms occur 2 to 24 weeks after exposure.

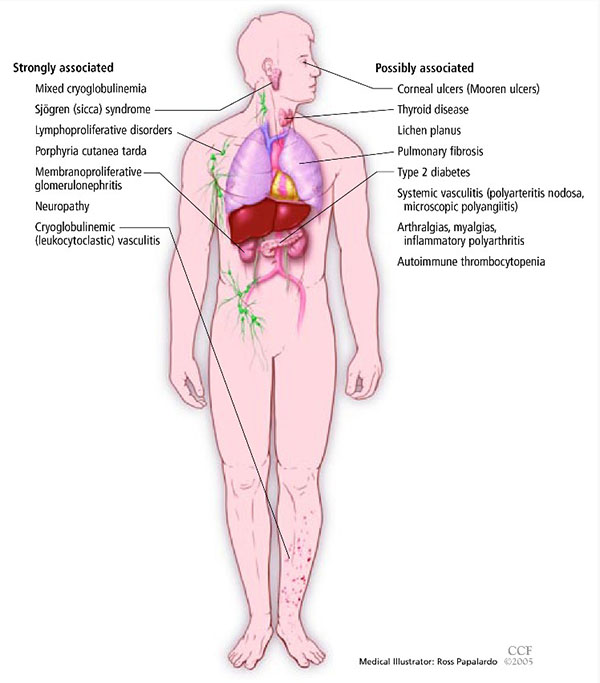

Many people with chronic HCV infection have no specific symptoms, and the finding of abnormal hepatic transaminase levels on routine testing often prompts specific testing for hepatitis C. Associated extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection may include mixed cryoglobulinemia, arthralgias, porphyria cutanea tarda, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C. Image Courtesy of Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Diagnosis of HCV infection is usually a two–step process:

- Identification of HCV antibodies then

- Demonstration of viremia and genotype.

The most common serologic test used to detect HCV antibodies is the enzyme–linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which has a 95% sensitivity and specificity. A positive test, particularly if the person has a risk factor for transmission, almost always represents either active viral infection or resolved HCV. The assay can detect HCV antibodies 4 to 10 weeks after infection. Confirmation of active infection in any person with a positive anti–HCV assay requires the detection of HCV RNA by PCR. HCV RNA appears in the blood and can be detected 2 to 3 weeks after infection.

There are two circumstances in which an individual infected with HCV may have a negative anti–HCV assay (a false negative result):

- Early, acute HCV infection in a person who has not developed antibody levels high enough to be detected;

- Individuals unable to mount an immune response and does not produce measurable antibody levels, such as those with HIV coinfection, renal failure, or HCV–associated mixed cryoglobulinemia.

A high clinical suspicion is important if the first situation arises. Acute hepatitis C should be suspected if clinical signs and symptoms (eg, jaundice and ALT elevation) are compatible with infection. In most cases, HCV RNA can be detected during the acute phase and should be checked if clinical suspicion is high. In the second circumstance, an immunosuppressed patient may not be able to mount an antibody response. Again, if clinical suspicion is high, the HCV RNA level should be checked to confirm infection.

An HCV viral quantitative assay ("viral load") defines the presence and amount of virus. The viral load does not define the likelihood of disease progression, severity of disease, or degree of liver damage. It is not necessary to check the viral load repeatedly.

People infected with HCV may have normal or elevated ALT values, limiting the value of this test in the diagnosis of HCV. Although most HCV–infected individuals with persistently normal ALT values have no hepatic fibrosis, it may be present in up to 25% of this population.

Assessment of Hepatic Fibrosis

There is a surprisingly high incidence of advanced hepatic fibrosis in HCV–infected people. In one study of non–cirrhotic individuals with HCV infection, 56.2% had evidence of fibrosis on liver biopsy. Identifying people with advanced fibrosis (F3 or F4) is important as it determines prognosis and need for further monitoring after infection treated. Individuals with advanced fibrosis need surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma and routine blood work for the detection of progressive disease or complications related to their underlying cirrhosis. The role of hepatic fibrosis in HCV treatment decision–making is discussed later.

Of note, noninvasive markers may be very good at separating out the extremes, but are limited in distinguishing specific levels of fibrosis between the extremes. Thus, they are best for people with a very low probability of significant fibrosis or those with a high likelihood of cirrhosis.

When common laboratory tests, imaging, and physical exam findings point to cirrhosis, additional testing is often unnecessary. Absence of such findings, however, does not provide evidence for absence of hepatic fibrosis or even cirrhosis. Therefore, for many with HCV infection, additional assessment is advised. The two types of noninvasive tests most often used are serum–based tests and imaging studies.

Serum–Based Testing

There are both proprietary and nonproprietary serum–based tests to detect hepatic fibrosis. The nonproprietary models are just as useful as the proprietarily ones and are recommended. One commonly used nonproprietary serum marker model is the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI). In a meta–analysis of 40 studies, an APRI score ([AST level/upper limit of normal AST]/platelet count) greater than 1.0 had a 76% specificity and 72% sensitivity for predicting cirrhosis. An APRI score greater than 0.7 had a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 72% for predicting significant hepatic fibrosis. Some evidence suggests that using multiple indices in combination or an algorithmic approach may result in higher diagnostic accuracy than using APRI alone. Another commonly used indirect serologic marker of fibrosis in Hepatitis C is the FibroSure® assay, a proprietary assay that classifies the degree of fibrosis using the following variables: alpha–2 macroglobulin, haptoglobin, gamma globulin, apolipoprotein A1, GGT, total bilirubin, patient age, and sex. Results classify people from F0 to F4. This test has 60% to 75% sensitivity and 80% to 90% specificity for detecting significant hepatic fibrosis. Other indirect serologic markers of fibrosis include the HepaScore®, AST/ALT ratio, FibroIndex®, and ActiTest®.

Transient Elastography

Transient elastography is increasingly used for staging hepatic fibrosis. It is painless, risk free, and lends itself to repeated measurement over time. FibroScan ® is the most widely available device; the majority of studies have employed this particular tool, and data from this are increasing woven into national and international practice guidelines. Elastography measures hepatic tissue stiffness using shear waves. Measurement of shear waves can be also done using MRI.

There is great experience with transient elastography in staging hepatic fibrosis in hepatitis C. In one typical study elastography had an 87% sensitivity and 91% specificity for the diagnosis of cirrhosis. In 7 of 9 studies in a meta–analysis, transient elastography diagnosed stage F2 to F4 fibrosis with 70% sensitivity and 84% specificity.

The major limitation of elastography is that results can be skewed in morbidly obese individuals. Elastography provides technically unreliable results in up to 15% of cases, and is especially unsuited for use in obese people. Fibroscan ® is contraindicated in those with pacemakers or defibrillators. As in serum based testing, elastography is most reliable when used either in people with no fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Liver Biopsy

Liver biopsy was formerly an important method for determining the degree of hepatic fibrosis in certain situations and has been considered the gold standard. Liver biopsy is associated with significant risk. Nearly 84% report pain after liver biopsy. Although much rarer, some patients have even worse complications: Severe bleeding occurs in 0.35% to 0.5%, perforation in 0.57%, and even death in approximately 0.03%. Not only do patients find liver biopsy anxiety–provoking, but physicians are averse to performing it. A recent survey of 104 physicians found that only 46.2% of them perform liver biopsy as the primary diagnostic tool. We no longer perform liver biopsies in most patients with HCV.

Treatment

Considered through the prism of individual and public health, even considering total societal costs, the most effective strategy is clearly to treat all HCV–infected people despite the high cost of medication. All individuals at any stage of hepatitis C should be considered for treatment. Higher overall cure rates improve patient–related outcomes, increase worker productivity, and ultimately lessen the economic burden of chronic HCV on society.

Chronic HCV–related liver disease puts a tremendous economic burden on infected individuals, their families, and society as a whole. In addition, as chronic HCV is a systemic disease with the potential to affect not only the liver but other organ systems, the disease burden can be enormous. From an economic standpoint, successfully treating this disease positively affects the entire community.

Those cured of chronic HCV have a reduction in liver inflammation. There is clear evidence that hepatic fibrosis and even cirrhosis is reversible when HCV is eliminated. This, in turn, is associated with a more than 70% reduction in the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and 90% reduction in the risk of liver–related death and liver transplantation.

Achieving cure has been shown to improve social, physical, and emotional health of those infected with HCV. In a large study of 4,781 people with chronic HCV infection, both depression (found in 30%) and poor physical health (found in 25%) were associated with unemployment, higher stressful events, and lower social support. Cure of HCV was associated with a lower risk of depression and with better physical health.

Benefits of cure accrue regardless of the stage of fibrosis at baseline. Even people with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis realize as much as an 80% reduction in the risk of developing clinical decompensation. A number of studies have also shown a decrease in the risk of specific complications, including a decrease of as much as 77% in the risk of development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Fibrosis may also improve. Among those with lesser degrees of liver damage, studies suggest a decrease in the degree of liver fibrosis in treated individuals and, in a minority of people, regression of cirrhosis.

The ideal treatment for HCV would have the following attributes:

- Highly effective

- Low cost

- Few side effects

- Easy to administer

- Lack of significant drug – drug interactions

- No need for treatment monitoring

Cost

All treatments for Hepatitis C are expensive. Typical costs are indicated below. As most people cannot cover these costs, payment and authorization for treatment falls to insurance companies. Because of limited resources, insurers have established a triage strategy. These vary between companies.

General Treatment Principles

The goal of treatment is permanent elimination of virus. Absence of virus in the blood 12 weeks after ending treatment is referred to as sustained virologic response (SVR). Increasingly, SVR and “cure” are used interchangeably and will be so used in this chapter. By convention, SVR determination is made 12 (or more) weeks after cessation of antiviral treatment. This is sometimes called SVR 12. Those who achieve an SVR have HCV antibodies but no longer have detectable levels of HCV RNA.

Patient Assessment

Pretreatment assessment of the patient with chronic hepatitis C should include the following:

- HCV viral load

- HCV genotype (once per lifetime)

- Complete blood count (CBC) including platelet count, hepatic function panel, international normalization ratio, basic metabolic panel

- Assessment of the level of liver fibrosis

- Anti–HAV (total). Immunization against hepatitis A should be considered if negative

- Hepatitis B markers (hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg], hepatitis B core antibody [anti-HBc], hepatitis B surface antibody [anti–HBs]) (Immunize those with negative markers. In people with serologic evidence of HBV infection, measure a baseline HBV DNA prior to treatment.)

- HIV status

Treatment Regimens

It is highly recommended that the full prescribing information packet be reviewed before prescribing any drug, including those discussed here.

There are many FDA–approved medications for treatment of HCV. Most combine two or more antivirals targeting different steps in the viral replication process. This chapter focuses on those regimens that make the most sense for general practitioners in the U.S. to treat people without decompensated cirrhosis, advanced renal insufficiency (eGFR >30), or coinfection with hepatitis B or HIV. Individuals with advanced cirrhosis or with a coinfection (HIV or HBV) should be seen by a healthcare provider with special expertise in gastroenterology, hepatology, or infectious disease. Those with significant renal insufficiency (eGFR <30) also should be treated by a specialist.

First–Line Therapy

The three pan-genotypic hepatitis drugs are described here, in descending order of value. Prices cited are from (https://www.verywellhealth.com/list-of-approved-hepatitis-c-drugs-3576465) accessed on February 7, 2021. Considerable negotiation between insurers and pharmaceutical manufacturers makes actual costs opaque and subject to frequent change.

Mavyret ® (Maviret ® in European Union) is a combination of glecaprevir (100 mg) and pibrentasvir (40 mg). Three tablets are taken all at once each day for 8 weeks (12 weeks if cirrhosis is present). This drug is not approved for those with decompensated cirrhosis. It is highly effective against all 6 hepatitis c genotypes. The rate of cure is > 98%. Based on public prices, this if the least costly treatment for hepatitis C. As of January 2020 the average wholesale price (AWP) of Mavyret was $26,400 for an 8-week course and $39,600 for a 12-week course.

Epclusa ® is a combination of sofusbuvir and velpatasvir. One tablet per day is taken for 12 weeks. It is approved for those with and without cirrhosis. This drug is not approved for those with decompensated cirrhosis. It is highly effective against all 6 hepatitis c genotypes. The rate of cure is > 98%. As of January 2020 the average wholesale price (AWP) of Epclusa ® was $89,700 for an 8-week course. A generic formulation of this combination is available that is cost-competitive with Mavyret ®.

Vosevi ® is a combination of sofosbuvir (400 mg), velpatasvir (100 mg) and voxilaprevir (100 mg). One tablet per day is taken for 12 weeks. It is approved for treatment of those who have failed previous hepatitis C treatment, regardless of genotype. The cure rate in these difficult to treat patients is 91% for those with genotype 3, and > 95% for other genotypes. This drug is not approved for those with decompensated cirrhosis. Those without cirrhosis and with compensated cirrhosis may use this agent. This drug is not approved for those with decompensated cirrhosis. As of January 2020 the average wholesale price (AWP) of Vosevi ® was $74,760 for a 12-week course.

A previously top-selling drug, Harvoni ® (sofosbuvir 400 mg, ledipasvir 90 mg) is also highly effective but not for genotype 2 or genotype 3 hepatitis C. Those without cirrhosis and with compensated cirrhosis may use this agent. This drug is not approved for those with decompensated cirrhosis. One pill is taken daily for 8 weeks in those without cirrhosis; 12 weeks for those with compensated cirrhosis. This drug is not approved for those with decompensated cirrhosis. The cure rate is > 95%. As of January 2020 the average wholesale price (AWP) of Harvoni was $94,500 for a 12-week course.

Because of the small risk of reactivation of hepatitis B in those treated for HCV, care must be taken to obviate this risk. A positive hepatitis B c antibody (anti HBc) defines a person exposed to hepatitis B virus and therefore at risk for reactivation. Those who are, in addition, positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg) are at more risk.

Second–Line Therapy

Drugs effective against only selected genotypes include

Zepatier ® (grazoprevir, elbasvir) effective against HCV genotype 1a, 1b, and 4

Technivie ® (partaprevir, ritonavir, ombitsavir) effective against HCV genotype 4

These drugs are seldom prescribed.

Side Effects and Drug–Drug Interactions

The direct–acting antivirals have an excellent side effect profile and are generally well tolerated. The most common side effects of are headache (22%), fatigue (15%), nausea (9%), asthenia

A major drug interaction with both of these drugs occurs with amiodarone. Serious symptomatic bradycardia (slow heart rate) has been associated with velpatasvir–sofosbuvir and amiodarone, especially in those with advanced liver disease or underlying heart disease. Therefore, co-administration of velpatasvir–sofosbuvir or amiodarone is not recommended for people without alternative treatment options.

In addition, drugs that are inducers of P–glycoprotein and/or inducers of certain cytochrome P enzymes may decrease the serum concentrations of sofosbuvir and/or velpatasvir resulting in a decreased potency of the combination. Certain established clinically significant drug interactions have also been described. Statins and proton pump inhibitors are generally held during treatment of hepatitis C.

Monitoring During Treatment

Confirmation of treatment success is demonstrated by the absence of HCV virus in the blood 12 or more weeks after completion of therapy. This has been termed sustained virologic response. (SVR). Such represents a cure. An individual with no- or minimal fibrosis who achieves an SVR needs no further follow-up. The rare individual who fails to achieve an SVR is most often referred to a gastroenterologist, hepatologist, or infectious disease specialist to consider retreatment.

The individual who has cirrhosis should be monitored even after cure for possible progression, decompensation, etc. It is becoming apparent that a minority of individuals with cirrhosis from hepatitis C may undergoing significant improvement in the degree of hepatic fibrosis, and even disappearance of cirrhosis.

In the absence of liver biopsy, cirrhosis is presumed in the presence of otherwise unexplained thrombocytopenia, or the presence of ascites, esophageal varices, or other markers of cirrhosis. Increasingly, elastography (e.g., by Fibroscan ®) is employed as non-invasive method of staging hepatic fibrosis. Cirrhosis is termed F-4. Fibroscan ® revealing > 15 KPA liver stiffness is highly associated with cirrhosis. Those with the next lowest fibrosis score (F-3) implies bridging fibrosis. Together, F-3 and F-4 fibrosis are termed advanced fibrosis.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a risk for those with advanced fibrosis. Importantly, this risk diminishes but does not disappear even after HCV cured. Such individuals should be screened for hepatocellular carcinoma every 6 months with a right upper quadrant ultrasound.

Contraindications

The only contraindication to current chronic HCV treatment is in a patient with a short–life expectancy that cannot be lengthened with treatment, with liver transplant, or with any other treatments.

Acute Hepatitis C

Acute HCV infection is frequently undiagnosed due to lack of specific symptoms. Because up to 50% of acutely infected individuals will spontaneously clear the infection, a balance must be struck between watchful waiting and treatment. At minimum, monitoring for HCV RNA for at least 3 months before starting treatment is recommended to allow for spontaneous clearance; however, delaying for 6 months is also acceptable. In people who are anti–HCV positive and HCV RNA negative (ie, spontaneous clearance of infection), HCV RNA should be tested again in 3 months to confirm true clearance.

Healthcare workers accidentally exposed to HCV-infected blood via a needle–stick injury should immediately report the exposure. They should have immediate testing for anti–HCV antibodies to establish the absence of pre–existing infection. There is no value to administration of either serum immune globulin or prophylactic antiviral treatment. The average incidence of anti–HCV seroconversion after needle–stick from a known anti–HCV positive source is 0% to 10.3%.

For individuals diagnosed with acute HCV infection (i.e., positive anti–HCV antibodies and positive HCV RNA), there is no clear benefit to early treatment. Monitoring for 6 months is acceptable as most cases will spontaneously clear without intervention. When the decision is made to initiate treatment after 6 months, treating as described for chronic hepatitis C is recommended, given its high efficacy and safety. In addition, insurance reimbursement plans have not made an exception to the general requirement that significant fibrosis must be present for payment, making the issue of early treatment essentially moot.

Studies of the predictors of spontaneous clearance of HCV infection have suggested that clearance may be more likely to occur in younger people and in those with a more symptomatic presentation, particularly with jaundice.

Transplantation using HCV-infected donor organs.

Patients awaiting organ transplantation of experience very long delays caused by a shortage or organs. To increase supply, and in recognition of the ease of treatment of HCV, organs from infected donors are now offered to those who indicate a willingness to accept such. Treatment is initiated as soon after transplantation as virus is detected and continued for 12 weeks. The success in elimination of HCV is organ recipients is > 98%. Some centers have adopted an approach of not waiting for HCV to emerge in the recipient but to give antivirals at the time of transplant and for a period as short as one week after. In these programs, success in preventing HCV is > 97%. In the few who acquire HCV despite pre-emptive treatment, and additional 12 weeks of therapy eliminates the infection.

Difficult–to–Treat Populations

These individuals are best managed by specialists, so they are only briefly described here.

Decompensated Cirrhosis

Decompensated cirrhosis is defined as Child–Pugh Classification B or C. It also can be defined clinically by the development of liver decompensation, such as jaundice, or complications of portal hypertension, such as ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy Treatment decisions for people with decompensated cirrhosis should be made by a hepatologist, preferably in the context of a liver transplant program.

HCV Following Liver Transplant

Infection of the new liver is almost universal post-transplant, and the subsequent rate of hepatic fibrosis can be quite rapid. The likelihood of a patient developing cirrhosis in the newly transplanted liver over the course of 3 to 5 years post-transplant, is as high as 10% to 30%.

In a small subgroup of individuals following liver transplant with HCV (27 of 179), the pattern of recurrence, with mainly cholestatic features (fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis), and the rate of disease progression is much more aggressive, leading to death in 1 to 3 years in up to 60% of these individuals.

HCV in Chronic Kidney Disease

Hepatitis C adversely affects survival in those with chronic kidney disease, especially those on dialysis. In addition, HCV seems to play a role in the rate of progression of kidney disease. Drug metabolism of many of the drugs used for HCV is altered in people with severe renal impairment and those on dialysis. Sufficient data is available for the following statement to be made by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the Infectious Disease Society of America:

No dose adjustment in direct-acting antivirals is required when using recommended regimens

Excellent cure rates have been shown for direct acting agents in chronic kidney disease including those on dialysis.

HIV–Hepatitis C Coinfection

Patients with HCV infection often share risk factors for coinfection with both hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HIV. HIV is known to accelerate HCV disease progression. With the use of direct–acting antivirals, those co-infected with HIV and HCV can be reliably treated with a traditional 12-week course. The importance of treatment is clear – those successfully treated are at a substantially lower risk of developing liver disease, complications of liver disease, or suffering a liver–related death. However, there are major issues with drug–drug interactions with direct-acting-agents and several of the medications used to control HIV. These are outlined in the AASLD/IDA practice guideline (HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis (https://www.hcvguidelines.org/) .

Hepatitis B–Hepatitis C Coinfection

The clinical course of HCV is thought to be worsened by HBV coinfection. Those with chronic HCV and active HBV coinfection have a more severe degree of liver fibrosis and a higher risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma than with HCV alone. Some studies, however, have suggested that an active HBV infection, but not previous infection, actually suppresses the replication of H. One study in anti–HCV positive subjects found a significantly lower prevalence of HCV RNA (41%) in those with active HBV infection than in those who had recovered from HBV infection (82%).

Several cases of reactivation of dormant hepatitis B have been reported when treatment of HCV is undertaken, including a few with severe liver injury requiring urgent liver transplantation. Those who are anti–HBc positive (whether they have HBsAg and even when HBV DNA levels are undetectable) are at risk. Because of this, we recommend referral of these people to a specialist for HCV treatment whenever anti–HBc or HBsAg is present.

Hepatitis C and Alcohol Use

Currently, alcohol use and HCV infection are the two primary causes of cirrhosis and liver transplantation in the U.S. Concurrent alcohol use is a common occurrence in people with chronic HCV. Because alcohol intake varies over time and affects individuals differently, it has been difficult to find an exact threshold for the risk to a person with HCV infection and concomitant alcohol use.

It is clear, however, that heavy alcohol use (defined as 5 or more drinks per day) contributes to HCV–associated liver disease. In a study of 6,600 people with HCV, higher alcohol intake was associated with significantly more cirrhosis compared with lower alcohol intake. Moreover, studies have shown that even lower amounts of alcohol were associated with fibrosis, although to a lesser extent than heavy alcohol use.

Therefore, it is quite clear that alcohol intake increases the risk of cirrhosis alone and particularly in combination with HCV. As cirrhosis is the primary risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma, alcohol use is associated with this cancer risk through its cirrhosis effect.

According to the U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs, those with chronic HCV likely should not drink alcohol as any amount can contribute to worsening liver disease. Heavy alcohol use, in particular, has been linked with fibrosis progression and cirrhosis although even light and moderate amounts do so to a lesser degree. People with established cirrhosis should definitely abstain from alcohol use.

Hepatitis C and Pregnancy

It is now recommended that women be tested for hepatitis C during each pregnancy. Women who test positive for hepatitis C do not need to be treated while pregnant. The average rate of HCV transmission from a HCV–infected mother to child is 5% to 6% if the mother is HIV–negative and up to 14% if the mother is HIV–positive. There is no known method of preventing perinatal transmission of HCV. Luckily, spontaneous resolution of HCV occurs in approximately 50% of HCV–infected infants within the first 3 years of life, so HCV treatment should not be considered before 3 years of age. Children who do not clear the virus should be closely followed by a specialist.

Hepatitis C virus is not spread through breast milk. The Centers for Disease Control endorses breast feeding in HCV infected women unless her nipples are cracked and bleeding, or in the event of HIV–HCV coinfection.

Typically, pregnant woman are not offered hepatitis C treatment. Occasionally, a woman being treated for HCV will become pregnant. It is unknown whether or not Mavyret ®, Epclusa ®, or Vosevi ® poses a risk to the developing human fetus, is excreted in human milk, or poses adverse effect on nursing infants. Animal studies suggest lack of risk, but human data are scant.

Any combination that contains ribavirin, a known teratogenic agent, must be assiduously avoided in both female and male partners. At least 2 reliable methods of birth control are recommended for any individual who is receiving ribavirin or who has done so within the preceding 6 months.

Conclusions

HCV infection becomes chronic in most and it can lead to cirrhosis in as many as 20% over a 20–year period. Serum aminotransferase levels reflecting hepatocellular injury can fluctuate, as does the viral load, making them unreliable markers of disease severity.

As the disease evolves, hepatocytes are progressively destroyed, often replaced by fibrosis, slowly leading to the development cirrhosis unless it is treated. The pathologic course is affected by various factors, such as the patient’s age at onset of infection, sex, coinfection with other viruses, other medical conditions, and risk behaviors. The risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma in people with chronic HCV plus cirrhosis is as high as 4% per year. HCV–infected individuals with cirrhosis should be followed by a liver specialist.

Direct–acting antiviral agents have made it possible to cure most cases of HCV infection. Although successful treatment with these regimens is associated with a lower rate of liver–related complications, and perhaps even regression of fibrosis/cirrhosis, those successfully treated may still be at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma if they have cirrhosis.

Although HCV remains a major global health problem, significant advances in the understanding of its basic biology have allowed improvements in treatment. Given the pace of discovery in this field, it may one day be possible to eradicate this deadly virus.

Key Points

- Hepatitis C infection remains one of the most important clinical and public health problems facing modern medicine. In the U.S., an estimated 3.5 million people are infected with HCV, and roughly half do not know they are infected. Approximately 75% to 85% of infected individuals will develop chronic HCV infection.

- Currently, the most common route of transmission is related to intravenous drug use. Other modes of transmission include having multiple sexual partners, tattooing, body piercing, and sharing straws during intranasal cocaine use. All adults should be screened for HCV.

- Diagnosis of HCV infection is usually a two–step process. First, identify HCV antibodies with an anti–HCV lab test, and second, confirm the diagnosis with demonstration of viremia by checking the HCV viral load.

- Distinction between HCV as an infection, on the one hand, and a liver disease, on the other, is important. Most people with HCV have little or no visible evidence of liver damage, and if infection is confirmed, management of the underlying infection is all that needs to concern the clinician. Once cured of infection, no additional follow up is needed in this subset of patients. We recommend assessing liver fibrosis in patients with HCV by using noninvasive radiologic modalities or serum–based markers.

- The only contraindication to current chronic HCV treatment is in a patient with a short life expectancy that cannot be lengthened with treatment, with liver transplant, or with any other treatments. Currently, the major barrier to treatment is the financial cost of the medication.

- Patients with stage F3 or F4 liver fibrosis should be followed by a specialist for liver–related complications. Those with decompensated cirrhosis, post–liver transplant HCV, chronic kidney disease, HCV–HIV coinfection, HCV–HBV coinfection, or who are pregnant should have their HCV infection managed by a specialist.

Suggested Reading

- HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis https://www.hcvguidelines.org/

- Global Health Sector Strategy on viral hepatitis. Towards ending viral hepatitis. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246177/WHO-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf?sequence=1

Additional Reading

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C FAQs for health professionals. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C kills more Americans than any other infectious disease. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0504-hepc-mortality.html. Accessed November 2, 2016.

- Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C: the OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet 1997; 349:825–832.

- Marcolongo M, Young B, Dal Pero F, et al. A seven–gene signature (cirrhosis risk score) predicts liver fibrosis progression in patients with initially mild chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2009; 50:1038–1044.

- Pawlotsky JM, Chevaliez S, McHutchison JG. The hepatitis C virus life cycle as a target for new antiviral therapies. Gastroenterology 2007; 132:1979–1998.

- Burlone ME, Budkowska A. Hepatitis C virus cell entry: role of lipoproteins and cellular receptors. J Gen Virol 2009; 90:1055–1070.

- Martell M, Esteban JI, Quer J, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) circulates as a population of different but closely related genomes: quasispecies nature of HCV genome distribution. J Virol 1992; 66:3225–3229.

- Manos MM, Shvachko VA, Murphy RC, Arduino JM, Shire NJ. Distribution of hepatitis C virus genotypes in a diverse U.S. integrated health care population. J Med Virol 2012; 84:1744–1750.

- Schreiber GB, Busch MP, Kleinman SH, Korelitz JJ. The risk of transfusion–transmitted viral infections: the Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:1685–1690.

- Karmochkine M, Carrat F, Dos Santos O, Cacoub P, Raguin G. A case–control study of risk factors for hepatitis C infection in patients with unexplained routes of infection. J Viral Hepat 2006; 13:775–782.

- European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network. A significant sex–but not elective cesarean section–effect on mother–to–child transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:1872–1879.

- Cottrell EB, Chou R, Wasson N, Rahman B, Guise JM. Reducing risk for mother–to–infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158:109–113.

- Yazdanpanah Y, De Carli G, Migueres B, et al. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus transmission to health care workers after occupational exposure: a European case–control study. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1423–1430.

- Terrault NA, Dodge JL, Murphy EL, et al. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among monogamous heterosexual couples: the HCV partners study. Hepatology 2013; 57:881–889.

- Moyer VA; for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159:349–357.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Screening veterans for hepatitis C infection. Available at: http://www.hepatitis.va.gov/provider/reviews/screening.asp. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis – Hepatitis C information. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/abc/index.htm. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep 2012; 61(RR-4):1–32.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis – CDC recommendations for specific populations and settings. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/populations/1945-1965.htm. Updated May 31, 2015. Accessed December 9, 2016.

- Cacoub P, Gragnani L, Comarmond C, Zignego AL. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46(Suppl 5):S165–S173.

- Ali A, Zein NN. Hepatitis C infection: a systemic disease with extrahepatic manifestations. Cleve Clin J Med 2005; 72:1005–1016.

- Krajden M, Ziermann R, Khan A, et al. Qualitative detection of hepatitis C virus RNA: comparison of analytical sensitivity, clinical performance, and workflow of the Cobas Amplicor HCV test version 2.0 and the HCV RNA transcription–mediated amplification qualitative assay. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:2903–2907.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Testing for HCV infection: an update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:362–365. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/pdfs/hcv_graph.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Hepatitis C RNA quantitative testing. Available at: http://www.hepatitis.va.gov/patient/hcv/diagnosis/labtests-RNA-quantitative-testing.asp. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2011; 55:245–264.

- Puoti C, Guarisco R, Spilabotti L, et al. Should we treat HCV carriers with normal ALT levels? The '5Ws' dilemma. J Viral Hepat 2012; 19:229–235.

- Saadeh S, Cammell G, Carey WD, Younossi Z, Barnes D, Easley K. The role of liver biopsy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2001; 33:196–200.

- AASLD–IDSA. HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Updated July 6, 2016. Available at: www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed October 31, 2016.

- Carey E, Carey WD. Noninvasive tests for liver disease, fibrosis, and cirrhosis: is liver biopsy obsolete? Cleve Clin J Med 2010; 77:519–527.

- Lin ZH, Xin YN, Dong QJ, et al. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase–to–platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C–related fibrosis: an updated meta–analysis. Hepatology 2011; 53:726–736.

- European Association for Study of Liver; Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Higado. EASL–ALEH Clinical Practice Guidelines: non–invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol 2015; 63:237–264.

- Gara N Zhao X, Kleiner DE, et al. Discordance among transient elastography, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index, and histologic assessments of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11:303–308.

- Talwalkar JA, Kurtz DM, Schoenleber SJ, et al. Ultrasound–based transient elastography for the detection of hepatic fibrosis: systematic review and meta–analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:1214–2020.

- Myers RP, Pomier–Layrargues G, Kirsch R, et al. Feasibility and diagnostic performance of the FibroScan XL probe for liver stiffness measurement in overweight and obese patients. Hepatology 2012; 55:199–208.

- Rockey D, Caldwell S, Goodman Z, Nelson RC, Smith AD; for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver biopsy. Hepatology 2009; 49:1017–1044.

- Sebastiani G, Ghali P, Wong P, Klein MB, Deschenes M, Myers RP. Physicians' practices for diagnosing liver fibrosis in chronic liver diseases: a nationwide, Canadian survey. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 28:23–30.

- Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:495–500.

- Regev A, Berho M, Jeffers LJ, et al. Sampling error and intraobserver variation in liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2614–2618.

- Younossi Z, Henry L. The impact of the new antiviral regimens on patient reported outcomes and health economics of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Liver Dis 2014; 46(Suppl 5):S186–S196.

- Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Smith BD, Liffmann DK, Ward JW. The cost–effectiveness, health benefits, and financial costs of new antiviral treatments for hepatitis C virus. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:157–168.

- Younossi ZM, Park H, Saab S, Ahmed A, Dieterich D, Gordon SC. Cost-effectiveness of all–oral ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimens in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41:544–563.

- Younossi ZM, Park H, Dieterich D, Saab S, Ahmed A, Gordon SC. Assessment of cost of innovation versus the value of health gains associated with treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the United States: the quality–adjusted cost of care. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95:e5048.

- Najafzadeh M, Andersson K, Shrank WH, et al. Cost–effectiveness of novel regimens for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. Ann Intern Med 2015; 162:407–419.

- Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck–Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta–analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158(5 Pt 1):329–337.

- van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all–cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA 2012; 308:2584–2593.

- Boscarino JA, Lu M, Moorman AC, et al; for the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS) Investigators. Predictors of poor mental and physical health status among patients with chronic hepatitis C infection: the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS). Hepatology 2015; 61:802–811.

- Veldt BJ, Heathcote EJ, Wedemeyer H, et al. Sustained virologic response and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:677–684.

- Mallet V, Gilgenkrantz H, Serpaggi J, et al. Brief communication: the relationship of regression of cirrhosis to outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149:399–403.

- McGowan CE, Fried MW. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment. Liver Int. 2012. Feb;32 Suppl 1:151–6.

- Sofosbuvir–Velpatasvir. Lexi–Drugs. Lexicomp. Riverwoods, IL: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Available at: http://online.lexi.com. Accessed Oct 1, 2016.

- Sofosbuvir–Ledipasvir. Lexi–Drugs. Lexicomp. Riverwoods, IL: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Available at: http://online.lexi.com. Accessed Oct 1, 2016.

- Epclusa (velpatasvir and sofosbuvir) tablets [prescribing information]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc; June 2016.

- Feld JJ, Jacobson C, Hézode T, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2599–2607.

- Harvoni (ledipasvir and sofosbuvir) tablets [prescribing information]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc; October 2014.

- Maheshwari A, Ray S, Thuluvath PJ. Acute hepatitis C. Lancet 2008; 372:321–332.

- Berenguer M, Ferrell L, Watson J, et al. HCV–related fibrosis progression following liver transplantation: increase in recent years. J Hepatol 2000; 32:673–684.

- Verna EC, Abdelmessih R, Salomao MA, Lefkowitch J, Moreira RK, Brown RS Jr. Cholestatic hepatitis C following liver transplantation: an outcome-based histological definition, clinical predictors, and prognosis. Liver Transpl 2013; 19:78–88.

- Sreekumar R, Gonzalez–Koch A, Maor–Kendler Y, et al. Early identification of recipients with progressive histologic recurrence of hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Hepatology 2000; 32:1125–1130.

- Fabrizi F, Martin P, Messa P. New treatment for hepatitis c in chronic kidney disease, dialysis, and transplant. Kidney Int 2016; 89:988–994.

- Limketkai BN, Mehta SH, Sutcliffe CG, et al. Relationship of liver disease stage and antiviral therapy with liver–related events and death in adults coinfected with HIV/HCV. JAMA 2012; 308:370–378.

- Weltman MD, Brotodihardjo A, Crewe EB, et al. Coinfection with hepatitis B and C or B, C and delta viruses results in severe chronic liver disease and responds poorly to interferon–alpha treatment. J Viral Hepat 1995; 2:39–45.

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about the risk of hepatitis B reactivating in some patients treated with direct–acting antivirals for hepatitis C. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm522932.htm. Published October 4, 2016. Accessed October 5, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Veteran's Affairs. Hepatitis C and alcohol. Available at: http://www.hepatitis.va.gov/provider/reviews/alcohol.asp. Accessed November 21, 2016.

- Monto A, Patel K, Bostrom A, et al. Risks of a range of alcohol intake on hepatitis C–related fibrosis. Hepatology 2004; 39:826–834.

- Tran T, Ahn J, Reau N. ACG clinical guideline: liver disease and pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111:176–194.

- Centers for Disease Control. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV–related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep 1998; 47:1–39.

- Ferrucci LM, Bell BP, Dhotre KB, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in chronic liver disease patients. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 44:e40–e45.

- Ahmed–Belkacem A, Ahnou N, Barbotte L, et al. Silibinin and related compounds are direct inhibitors of hepatitis C virus RNA–dependent RNA polymerase. Gastroenterology 2010; 138:1112–1122.

- Rambaldi A, Jacobs BP, Gluud C. Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 4:CD003620.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Hepatitis C: a focus on dietary supplements. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/hepatitisc/hepatitiscfacts.htm?nav=gsa. Updated November 2014. Accessed November 4, 2016.

- Sublette VA, Douglas MW, McCaffery K, George J, Perry KN. Psychological, lifestyle and social predictors of hepatitis C treatment response: a systematic review. Liver Int 2013; 33:894–903.