Definition

Andrea Fialho, MD

Andre Fialho, MD

William D. Carey, MD

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the liver of unknown etiology identified in the 1940s and formerly called chronic active hepatitis. Autoimmune hepatitis is characterized by liver transaminase elevation in the presence of autoantibodies, elevated gamma globulin levels, interface hepatitis on histology, and a great response to corticosteroids.

Epidemiology

Autoimmune hepatitis occurs worldwide but the exact incidence and prevalence of the disease in the United States is unknown. The point prevalence and incidence of AIH in Northern Europeans is approximately 18 per 100,000 people per year and 1.1 per 100,000 people per year, respectively, and it is assumed that this data can be extrapolated to the North American population. Interestingly the prevalence of AIH in Native Alaskan population is much higher, with a point prevalence of 42 per 100,000 people/year. Autoimmune hepatitis has a female predominance and a bimodal age distribution with 2 peaks, 1 in childhood and another in the 5th decade. However AIH occurs in both genders and in all age groups and there have been reports of newly diagnosed AIH in patients 80 years of age.

Subtypes

Autoimmune hepatitis is subdivided in 2 types, according to the pattern of autoantibodies. Although management does not differ between these 2 types, there is a prognostic value.

Type 1 AIH: This is the most common type in the United States, accounting for 96% of the AIH cases in North America, has a female to male ratio of 4 to 1 and a great response to corticosteroids. It is characterized by the presence of antinuclear antibody (ANA) and antismooth-muscle antibody (ASMA).

Type 2 AIH: This type occurs most often in Europe and the patients tend to be younger (usually less than 14 years old), have more severe disease, worse response to corticosteroids, and relapse more often. Type 2 AIH accounts for only 4% of the AIH cases in North America. It is characterized by the presence of anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody type 1 (anti-LKM1) and/or anti-liver cytosol type 1 (anti-LC1) autoantibodies.

Genetics and Predisposing Factors

Autoimmune hepatitis is thought to result from an environmental trigger in a genetically predisposed individual, leading to loss of tolerance of T lymphocytes with subsequent hepatocyte attack.

It is a polygenic disease and does not follow a Mendelian distribution. Therefore there is no need to screen family members of patients with AIH. There is a strong genetic association with the alleles of the major histocompatibility complex class II. The presence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes HLA DRB1*03 and HLA DRB1*04 predisposes to AIH type 1 and affect the disease course and response to treatment. Individuals who are positive for HLA DRB1*03 are younger, respond less favorably to corticosteroid therapy, and progress more often to liver failure. On the other hand, the presence of HLA DRB1*04 is associated with higher rates of concomitant autoimmune disorders.

Autoimmune hepatitis can also be associated with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy syndrome, an autosomal recessive disease characterized by hypoparathyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy is the only AIH-associated disease that follows a Mendelian pattern of inheritance and genetic counseling should be offered for patients and family members.

Viruses such as hepatitis A and Epstein Barr virus have been proposed as a potential environmental triggers for AIH through molecular mimicry. However available data consists mainly of case reports.

Drugs such as propylthiouracil, minocycline, and nitrofurantoin can cause drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DIAH) which is clinically, biochemically, and histologically indistinguishable from AIH but is a different entity. As in AIH, DIAH is characterized by female predominance, elevated liver transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT]) with minimal alkaline phosphatase elevation, positive autoantibodies, and interface hepatitis on liver biopsy. Similarly to AIH, ANA is positive in 70% to 80% of the cases and ASMA is positive in 40% to 50% of the cases. In addition to drug discontinuation, DIAH is treated with steroids and response is excellent. In contrast to AIH, 100% of the patients with DIAH will be able to have steroids withdrawn without relapse.Table 1 shows the most common drugs associated with DIAH.

Table 1: Drugs Associated With Drug-Induced Autoimmune-Like Hepatitis

| Association | Drug |

|---|---|

| Strong | Nitrofurantoin Minocycline Halothane |

| Probable | Atorvastatin Isoniazide Diclofenac Propylthiouracil Infliximab |

| Uncertain | Adalimumab Cephalexin Fenofibrate Indomethacin Imatinib Rosuvastatin Meloxicam Methylphenidate |

There is a strong association of AIH with other autoimmune diseases and up to 26% to 49% of the individuals with AIH will have concomitant autoimmune diseases. Autoimmune hepatitis type 1 is associated with autoimmune thyroiditis, Grave's disease, and ulcerative colitis while AIH type 2 is associated with diabetes mellitus type 1, vitiligo, and autoimmune thyroiditis.

Natural History

Autoimmune hepatitis was once a lethal condition with a dismal prognosis. Treatment with corticosteroids has changed the course of the disease and nowadays AIH can be considered a disease with relatively good prognosis in responsive patients.

Most of the data on untreated AIH comes from studies pursued in the 1970s, when the benefit of corticosteroids was established. Without treatment, approximately 40% to 50% of the individuals with severe disease will die within 6 months to 5 years. Treatment with steroids has dramatically changed the course of the disease. Most patients respond to therapy and the 10-year survival rate is approximately 83.8% to 94%. Thus prompt recognition of the disease and initiation of treatment is critical.

Symptoms

The clinical presentation of autoimmune hepatitis varies from asymptomatic to acute liver failure. Symptoms of anorexia, arthralgias, maculopapular rash, and fatigue are typical but not always present. Most patients will have an insidious onset with constitutional symptoms, 25% of patients will be asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally, and 30% of patients will have acute hepatitis manifestations, the later occurring more often in younger patients. Severe acute hepatitis similar to viral hepatitis can occur. Fulminant hepatic failure is rare and appears to be more common in AIH type 2.

Diagnosis

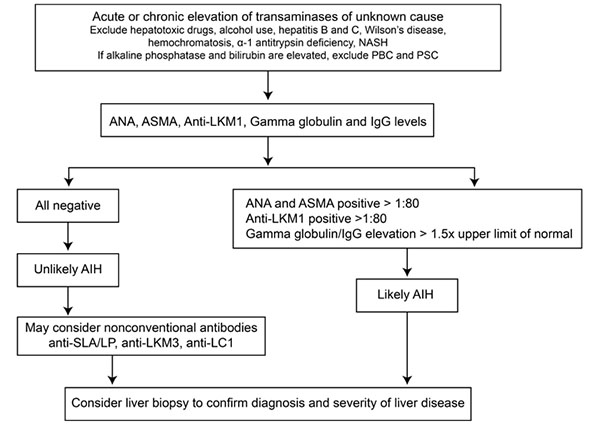

No single test is diagnostic for AIH. The diagnosis of AIH is based on a combination of characteristic clinical features and typical laboratory abnormalities. Other causes of chronic hepatitis should be excluded, including alcohol induced hepatitis, drug-induced hepatitis, and viral hepatitis. Table 2 shows simplified diagnostic criteria for AIH and Figure 1 shows a simplified diagnostic algorithm for AIH.

Figure 1: Simplified diagnostic algorithm for autoimmune hepatitis. AIH = autoimmune hepatitis; ANA = antinuclear antibody; ASMA = antismooth-muscle antibody; IgG = immunoglobulin G; anti-LC1 = anti-liver cytosol type 1 antibody; anti-LKM1 = anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody type 1; anti-LKM3 = anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody type 3; NASH = nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; PBC = primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC = primary sclerosing cholangitis; anti-SLA/LP = anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas antibody.

In the majority of cases, AIH diagnosis can be made by using Table 2. When patients do not meet all the criteria in Table 2 or have atypical features, the diagnosis of AIH becomes less certain and they should be referred to a gastroenterologist or hepatologist.

Table 2: Diagnosis of Autoimmune Hepatitis

| Diagnostic Criteria |

|---|

| Elevation of AST/ALT 5–10 times upper limit of normal |

| Gamma globulins or IgG levels ≥1.5 times upper limit of normal |

| Positive ANA, ASMA or Anti-LKM1 in titers >1:80 |

| Female sex |

| Negative markers for hepatitis A,B and C and Wilson's disease |

| Alcohol consumption of less than 25 g/day |

| Absence of hepatotoxic drugs |

Interpretation of Table 2: Autoimmune hepatitis is diagnosed when all of the above diagnostic criteria are met. Liver biopsy under these circumstances can be relevant for assessing severity of AIH. If some of the criteria above are not met, diagnosis of AIH is less certain and patients should be referred to a gastroenterologist or hepatologist before starting treatment.

ANA = antinuclear antibody; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; ASMA = antismooth-muscle antibody; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; IgG = immunoglobulin G; anti-LKM1 = anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody type 1.

Laboratory Abnormalities

The major laboratory abnormalities encountered in AIH are elevation of liver transaminases and gamma globulins and the presence of autoantibodies.

Liver Enzyme Abnormalities

Elevation of liver transaminases less than 500 UI/L with normal alkaline phosphatase is typical. Liver transaminase elevation to 1,000 UI/L resembling acute viral hepatitis and liver ischemia is less common but can occur.

An elevation of alkaline phosphatase that is disproportional to transaminase ALT or AST elevation with an alkaline phosphatase to ALT or AST ratio of ≥3 is unusual and should prompt investigation of other causes of liver disease such as drug induced disease, primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

Individuals with AIH may concomitantly have features of other autoimmune liver diseases such as PSC or PBC, termed overlap syndrome. The overlap syndrome of AIH with PBC or AIH with PSC will be discussed separately further in this chapter.

Gamma Globulin Elevation

Gamma globulin elevation occurs in 80% of the cases. There is a polyclonal elevation in immunoglobulin (Ig), with a predominant IgG elevation. Along with liver transaminases, gamma globulin levels are important markers of disease activity.

Autoantibodies

As discussed previously in the epidemiology topic of this chapter, the presence of autoantibodies is common in AIH, most frequently ANA, ASMA, and anti-LKM1. See Table 3 for the differences between AIH type 1 and type 2 with regards to autoantibody profile. It is extremely rare to have the occurrence of antibodies to AIH type 1 (ANA and ASMA) and antibodies to AIH type 2 (anti-LKM1) in the same patient. In the few cases where this situation occurs, the course of disease is similar to AIH type 2.

Table 3: Autoantibody Interpretation in Autoimmune Hepatitis

| AIH type | Conventional Autoantibodies | Nonconventional Autoantibodies |

|---|---|---|

| AIH type 1* | ANA, ASMA | pANCA, anti-SLA/LP |

| AIH type 2** | Anti-LKM1 | Anti-LC1, anti-LKM3, anti-SLA/LP |

*Onset in adults, frequently acute (6% fulminant), corticosteroid responsive, cirrhosis in 35%

**Onset in childhood (age 2 to 14 years), usually indolent, more often corticosteroid refractory; cirrhosis in 80%

AIH = autoimmune hepatitis; ANA = antinuclear antibody; Anti-LC1 = anti-liver cytosol type 1 antibody; anti-LKM1 = anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody type 1; anti-LKM3 = anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody type 3; pANCA = perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; anti-SLA/LP = anti-soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas antibody; ASMA = antismooth-muscle antibody.

Approximately 20% of patients may lack ANA, ASMA, and anti-LKM1. In these cases, additional antibodies may be present such anti soluble liver antibody (anti-SLA), anti-LC1, and anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody type 3 (anti-LKM3).

The presence of anti-SLA can occur in AIH type 1 and type 2 and is associated with severe disease and worse prognosis. Both LC1 and LKM3 occur in type 2 AIH. These antibodies are not readily available in many institutions, hence the diagnosis of AIH when typical antibodies are negative will most often rely on histologic features.

Atypical perinuclear-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) can also be positive in AIH type 1 and may be an additional clue for the diagnosis when the conventional antibodies are negative. Antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) in low titers can occur in AIH and this does not imply superimposed PBC.

Liver Biopsy

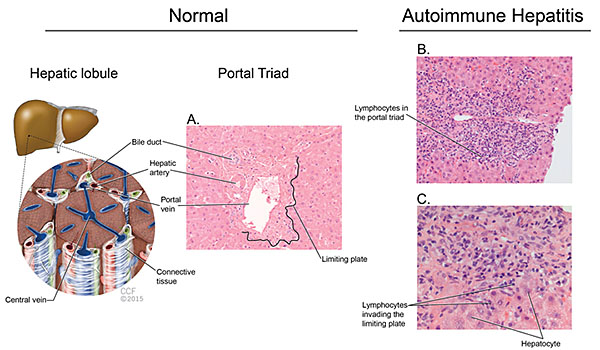

Liver biopsy should be considered for the diagnosis of AIH and it can provide valuable information regarding severity of the disease. The American Association for Study of Liver Diseases recommends a liver biopsy for diagnostic purposes. The hallmark of AIH on histology is interface hepatitis characterized by lymphocytic infiltrate in the portal triad that goes beyond the limiting plate and reaches the bordering hepatocytes. The bile ducts are intact. Interface hepatitis, although commonly seen in AIH, is not pathognomonic and can occur in other liver diseases. Figure 2 outlines the major histologic features of AIH. In severe acute autoimmune hepatitis one should not wait for biopsy results to start treatment, as delay in therapy has been associated with adverse outcomes.

Figure 2: Histologic hallmarks of autoimmune hepatitis. (A) Depiction of a normal hepatic lobule, note the clear delineation between the connective tissue of the portal triad and the hepatocytes. In autoimmune hepatitis, (B and C) lymphocytic infiltrate accumulates in the portal triad. Interface hepatitis (C) occurs when the lymphocytes in the portal triad invade the limiting plate spilling around the hepatocytes

Imaging

There is no role for routine imaging in the diagnosis of AIH. Because patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and AIH have high rates of PSC, they should have a cholangiographic study once AIH is diagnosed to rule out PSC. Unless otherwise contraindicated, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is usually the test of choice.

Treatment

Treatment is directed against inflammation and the cornerstone of therapy is corticosteroid therapy. Treatment is the same for type1 and type 2 AIH. Response to corticosteroid is usually excellent in AIH type 1, with 80% of the patients having normalization of liver function tests.

When to Start Treatment

Treatment should be started in patients with significant disease, characterized by at least one of the following: AST or ALT >10 times the upper limit of normal; AST or ALT >5 times the upper limit of normal and IgG >2 times the upper limit of normal; bridging necrosis or multiacinar necrosis on histology. Although uncommon, the presence of incapacitating symptoms (fatigue, arthralgia) has also been proposed as an indication of treatment regardless of laboratory values.

In asymptomatic patients with AST, ALT, and gamma globulins/IgG elevations that do not meet the criteria above, the benefit of treatment is less clear. The course of the disease in such patients has not been well established and there is little data to support treatment. Thus in asymptomatic patients with only mild laboratory and histological changes, the decision to start treatment should be individualized and the risks of therapy taken into account. Often treatment in this situation can be postponed and liver tests followed closely. Such patients should always be referred to a hepatologist or gastroenterologist for decision regarding therapy.

Asymptomatic patients with inactive disease (minimal or absent inflammation) on liver biopsy or burned out cirrhosis do not benefit from treatment.

Treatment Options

The most commonly used initial treatment options are immunosuppressive therapy with either 1) a combination of prednisone and azathioprine, 2) a combination of budesonide and azathioprine or 3) high-dose prednisone monotherapy.

The 2 most studied treatment regimens are high dose prednisone monotherapy or combination therapy of prednisone plus azathioprine. Both are equivalent in efficacy of induction of remission, but prednisone monotherapy is associated with higher rates of corticosteroid induced side effects. Hence combination therapy of prednisone and azathioprine should always be preferred unless contraindications to azathioprine exist.

More recently, combination therapy of budesonide plus azathioprine is emerging as a potential frontline treatment option for AIH. Budesonide is a corticosteroid that has 90% first-pass metabolism in the liver and thus has fewer systemic side effects than prednisone. This regimen has been compared with combination therapy of azathioprine 50 mg per day plus prednisone in a randomized, controlled trial and was shown to have better clinical and laboratory remission rates with fewer steroid induced side effects at 6 months after initiation of therapy. The main disadvantage of budesonide plus azathioprine combination therapy is that it is more expensive and to date there are no studies evaluating long-term remission with this regimen. It is a valuable option in patients with obesity, acne, diabetes, hypertension, and osteopenia who are at high risk of developing side effects from prednisone. Table 4 shows the main side effects and contraindications of each drug.

Table 4: Side Effects and Contraindications of the Most Commonly Used Drugs in Autoimmune Hepatitis

| Drug | Major Side Effects | Contraindications |

|---|---|---|

| Azathioprine | Nausea and vomiting Liver toxicity Myelosuppression Pancreatitis Malignancy (most often lymphoma) Rash |

Pregnancy Malignancy Leukopenia <2.5 x 109/L Thrombocytopenia <50 x 109 Known complete TPMT deficiency |

| Budesonide | Usually none Cosmetic changes (moon faces, acne and hirsutism) |

Cirrhosis |

| Prednisone | Osteoporosis Emotional instability Diabetes Hypertension Cosmetic changes (see budesonide) Cataracts Weight gain |

Vertebral compression Psychosis Brittle diabetes Uncontrolled hypertension |

TPMT = thiopurine methyltransferase.

The treatment of AIH consists of 2 phases: 1) induction of remission and 2) maintenance of remission. Please refer to Table 5 for detailed treatment regimens in each phase.

Table 5: Most Common Treatment Options for Autoimmune Hepatitis

| Combination Treatment Prednisone + Azathioprine |

Combination Treatment Budesonide + Azathioprine |

Prednisone Monotherapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction | ||||

| Week 1 | 30 mg/d + 50 mg/d | 9 mg/d + 50 mg/d | Prednisone 60 mg/d | |

| Week 2 | 25 mg/d + 50 mg/d | 9 mg/d + 50 mg/d | Prednisone 40 mg/d | |

| Week 3 | 20 mg/d + 50 mg/d | 6 mg/d + 50 mg/d | Prednisone 30 mg/d | |

| Week 4 | 15 mg/d + 50 mg/d | 6 mg/d + 50 mg/d | Prednisone 20 mg/d | |

| Maintenance | ||||

| First 12 months | Prednisone 10 mg/d + Azathioprine 50 mg/d | Budesonide 6 mg/d + Azathioprine 50 mg/d | Prednisone 20 mg/d or less for at least 24 months | |

| 12-24 months | Prednisone taper 2.5 mg/week until withdrawal. Thereafter azathioprine monotherapy 50-100 mg/day | Consider budesonide taper until withdrawal. Thereafter azathioprine monotherapy 50-100 mg/day | ||

| Treatment Withdrawal | ||||

| After 24 months of complete remission OR Liver biopsy showing absence of inflammation |

Same | Same | ||

| Indication | ||||

| Preferred over prednisone monotherapy as fewer side effects | Potential frontline therapy Patients with obesity, acne, diabetes, and hypertension may benefit |

Reserved for patients who cannot take azathioprine | ||

| Disadvantages | ||||

| Side effects of prednisone, although less often and less severe than high-dose prednisone | Expensive Fewer studies showing efficacy |

Severe corticosteroid induced side effects | ||

Induction Phase

In the induction phase, prednisone 30 mg per day plus azathioprine 50 mg per day is started for 1 week. This is followed by a prednisone taper over the course of 4 weeks with a fixed azathioprine dose of 50 mg per day to achieve a dose of prednisone 10 mg per day plus azathioprine 50 mg per day as shown in Table 5.

Should budesonide plus azathioprine be selected, induction is achieved with combination of budesonide 3 mg three times daily plus azathioprine 50 mg per day for 2 weeks, followed by a budesonide 3 mg twice daily thereafter.

Maintenance Phase

For those receiving prednisone plus azathioprine, maintenance phase begins typically after 4 weeks, when the dose of prednisone 10 mg per day plus azathioprine 50 mg per day is started. This dose is continued for at least 1 full year. The daily maintenance dose of prednisone should remained fixed, as dose titration according to liver transaminases or alternate day schedules of prednisone are associated with incomplete histological improvement despite laboratory improvement.

After 1 year of controlled disease, consideration can be given to withdrawal of prednisone while continuing azathioprine. Thereafter azathioprine monotherapy is continued for long-term maintenance. Patients can often be maintained on doses of azathioprine monotherapy of 50 mg per day to 100 mg per day with normal liver enzymes. Azathioprine doses of less than 100 mg per day have the advantage of less toxicity, particularly less leukopenia. Table 5 shows the medical regimen for AIH.

If budesonide is used, the maintenance dose is 6 mg twice daily in combination with azathioprine 50 mg per day. One may consider tapering budesonide while maintaining azathioprine 50 mg per day to 100 mg per day (azathioprine monotherapy) after 12 months, but there are currently no studies on the long term effect of azathioprine monotherapy after budesonide plus azathioprine combination.

Outcomes of Treatment

The goal of treatment is to prevent liver failure and end stage liver disease. Response to treatment is classified into remission, incomplete response or treatment failure.

Remission or complete response is considered the absence of symptoms, normal liver tests (transaminases, alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltransferase and IgG) and absence of inflammation on liver biopsy. It is usually achieved in 80% of the patients approximately 1 to 2 years after treatment initiation. In responsive patients, AST and ALT will often improve in 6 to 12 weeks after treatment initiation. Histological improvement usually lags behind laboratory improvement in 3 to 8 months.

Gradual treatment withdrawal over a 6-week period can be tried after biochemical and histological remission is achieved. Every patient should be given a chance of sustained remission off medication if they so desire. Withdrawal of treatment after normalization of laboratory tests for at least 2 years without the need for liver biopsy has been done. Many experts argue that a liver biopsy should be obtained prior to withdrawal because approximately 50% of patients have significant inflammation on liver biopsy despite normal liver transaminase and gamma globulin. Thus a liver biopsy prior to drug withdrawal is recommended to confirm absence of inflammation. Persistence of inflammation on liver biopsy predicts higher rates of recurrence and thus therapy withdrawal should not be attempted in this circumstance. During drug withdrawal, liver tests and gamma globulins should be monitored every 4 weeks for 3 months and then every 6 months thereafter to monitor for relapse of disease. Persistent elevation of transaminases and gamma globulins are invariably associated with inflammation on histology and thus withdrawal of treatment should not be attempted in this circumstance.

Disease relapse is common after complete therapy withdrawal. Approximately 80% of the patients that have treatment withdrawn will relapse. Relapse is characterized by AST/ALT more than 3 times the upper limit of normal and/or gamma globulin of more than 2 g/dL. Liver biopsy is not necessary to confirm relapse. Once relapse occurs, the initial treatment regimen of prednisone 30 mg per day plus azathioprine 50 mg per day should be restarted and then tapered again as done previously to a maintenance dose of prednisone 10 mg per day plus azathioprine 50 mg per day. Prednisone can be completely withdrawn while continuing azathioprine monotherapy 50 mg per day to 100 mg per day. Another trial of treatment withdrawal can be attempted, although most patients will need treatment indefinitely.

Patients who have improvement in liver transaminases, gamma globulins, and histology but do not achieve a complete response after 3 years of treatment are considered incomplete responders, and this occurs in 13% of the cases. These patients should be maintained indefinitely on the lowest dose of prednisone (goal ≤10 mg per day) that allows stabilization of liver transaminases, alone or in combination with azathioprine. Azathioprine monotherapy can also be used.

Treatment failure is considered worsening of liver transaminases while on conventional treatment and occurs in 7% of the patients. These patients should be started on prednisone 30 mg per day combined with azathioprine 150 mg per day for 1 month. Prednisone and azathioprine can then be reduced to prednisone 20 mg per day and azathioprine 100 mg per day for 1 month then reduced again to the regular maintenance of prednisone 10 mg per day and azathioprine 50 mg per day.

Liver transplantation is an option when patients present with acute liver failure, decompensated cirrhosis with a Model for End Stage Liver Disease score ≥15 or hepatocellular carcinoma that meets criteria for liver transplantation. Approximately 10% to 15% of AIH patients will require liver transplantation. Autoimmune hepatitis is a relatively uncommon indication for liver transplant (5% of all liver transplants) given that most patients can be managed medically with success. Survival rate is excellent after transplantation.

The most common immunosuppression regimen used in patients after liver transplant is the combination of calcineurin inhibitor, usually tacrolimus, with prednisone. Recurrence of AIH in the transplanted liver can occur in 25% to 30% of the cases and seems to be more common when prednisone is discontinued.b Thus prednisone is usually continued at low doses after transplant. Autoimmune hepatitis recurrence in the liver transplant can often be successfully treated by reintroducing prednisone and optimizing calcineurin inhibitors. A combination of prednisone and azathioprine has also been used to treat recurrent AIH. These patients have a similar prognosis as transplanted patients who do not have recurrent AIH.

De novo AIH in the transplanted liver can occur in individuals who did not have AIH prior to transplant. Treatment with prednisone and azathioprine as in AIH is usually successful. We will not undergo a detailed discussion on de novo AIH as it is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Alternative Treatment Options

Alternative treatment options are generally used when there is intolerance or contraindications to azathioprine or when treatment failure ensues. The most commonly used alternative agents are mycophenolate mophetil or calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) alone or in combination with prednisone. They have been used successfully, particularly for azathioprine intolerance. Mycophenolate mophetil and calcineurin inhibitors are both teratogenic and contraindicated in pregnancy.

Prednisone high-dose monotherapy is rarely used nowadays, but is still an option in pregnant patients and in patients who cannot tolerate azathioprine.

Other options that have been used successfully in treatment failure, although in a small number of patients, are rituximab and infliximab. The role of these medications in AIH merits further investigation. Ursodeoxycholic acid has been studied in AIH but did not provide any benefit.

Prognosis

In patients responsive to treatment, AIH has a good prognosis. The majority of treated patients will achieve remission and the 10-year survival rate approaches 83.8% to 94%. Most of the patients will need lifelong maintenance therapy as withdrawal of therapy leads to relapse in 80% of the patients within 3 years. The possibility of long-term maintenance on azathioprine monotherapy has reduced the long-term side effects of corticosteroid therapy.

In patients with established cirrhosis at the beginning of treatment, data on prognosis have been conflicting. While in 1 study, treatment in AIH with cirrhosis showed a 10-year life expectancy comparable to non-cirrhotics, another has shown that the 10-year life expectancy is reduced at 64%.

The outcomes are generally good in those patients who require liver transplantation. In these patients, survival is 75% at 8 years. Recurrence of AIH in the transplanted liver can occur and appears to be more common when prednisone is discontinued. Reintroduction of prednisone and optimization of calcineurin inhibitors usually induces remission. These patients have a similar prognosis as transplanted patients who do not have recurrent AIH.

Monitoring

We suggest the following tests to monitor patients with AIH.

Prior to treatment

- Pregnancy test

- Vaccination for hepatitis A and hepatitis B viruses

- Bone density in postmenopausal women

- Bone maintenance regimen of calcium and vitamin D supplementation and exercise for all patients

- Complete blood count to rule out severe cytopenia that would preclude azathioprine

During induction phase

- AST or ALT, total bilirubin concentration, and alkaline phosphatase every 1-2 weeks

During maintenance phase

- AST or ALT, total bilirubin concentration, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma globulin or IgG levels every 3-6 months

- Complete blood count every 6 months while on azathioprine

- Bone mineral density once a year while on prednisone

- Routine eye examination in patients on prednisone at least once a year

During treatment withdrawal

- AST or ALT, total bilirubin concentration, alkaline phosphatase ,and gamma globulin or IgG levels every month for 3 months, then every 6 months for 1 year and then yearly lifelong

When end stage liver disease ensues

- Hepatic ultrasonography every 6 months or computed tomography of the abdomen with contrast once a year to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy screening for esophageal varices every 2-3 years for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding

- Bone mineral density every 3 years

Considerations in Special Populations

Pregnancy

Best Treatment Option

The treatment of choice for AIH during pregnancy is prednisone. Azathioprine is rated as category D in pregnancy by the Food and Drug Administration because it has been shown to have teratogenic effects on animals. Thus azathioprine can theoretically cause malformation in human fetus and therefore discontinuation during pregnancy is recommended. However there have been studies in women with IBD showing that it is safe to use azathioprine during pregnancy.

Autoimmune Hepatitis Course in Pregnancy

Autoimmune hepatitis will often improve during pregnancy leading to dose reduction of treatment. Exacerbations may occur, usually in patients who are not on treatment during pregnancy or when AIH is in remission for less than 1 year prior to pregnancy. Approximately 30% to 50% of patients will have an AIH flare during pregnancy, most of which occur after delivery, in the immediate post-partum period. Thus conventional treatment should be restarted 2 weeks prior to expected delivery date and liver enzymes should be monitored every 3 weeks during the first 3 months after delivery.

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is safe during treatment with azathioprine. The active metabolite of azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, is excreted in breast milk although in much lower levels than therapeutic levels. No adverse effects have been shown to babies of mothers who are breastfeeding while taking azathioprine.

Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with AIH who also have IBD are more likely to have PSC. Thus all patients with IBD who are diagnosed with AIH should have cholangiographic studies, usually MRCP, to rule out PSC.

Overlap Syndromes

Some patients have features of AIH but also have characteristics of PBC or PSC. This is called overlap syndrome. The two most common forms of overlap syndromes are: 1) PBC with features of AIH and 2) AIH with features of PSC. Although the overlap syndromes often exist concomitantly at time of diagnosis, sometimes they can exist sequentially. The clinical picture of overlap syndromes is often dynamic and the initial prevailing diagnosis may change with time.

There are no standardized diagnostic criteria for overlap syndromes and thus their true prevalence is unknown. Overlap syndromes in AIH are often suggested by the existence of markedly elevated alkaline phosphatase or positive AMA. Unresponsiveness to therapy in a previously responsive patient should raise suspicion for overlap syndrome. The identification of overlap syndromes is important as treatment and outcome may be different from classic AIH.

Autoimmune Hepatitis and Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Overlap Syndrome

In patients with AIH or PBC, the prevalence of overlap features is approximately 8% to 19%. When the disease has a sequential presentation, PBC is usually diagnosed first and AIH occurs later.

Patients typically have an elevated AST, ALT, and gamma globulins typical of AIH and also elevated alkaline phosphatase and IgM characteristic of PBC. The AMA may be present, often in high titers. There are no standardized criteria for the diagnosis of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. Simplified diagnostic criteria have been proposed and are commonly used to aid diagnosis as shown in Table 6.

AIH-PBC overlap syndrome is diagnosed in the presence of 2 or more diagnostic criteria for AIH and 2 or more diagnostic criteria for PBC.

Table 6: Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Hepatitis-Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Overlap

| Diagnosis of AIH-PBC Overlap |

|---|

| Presence of 2 of 3 AIH features: |

|

| AND |

| Presence of 2 of 3 PBC features: |

|

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AMA = antimitochondrial antibodies; GGT = gamma-glutamyl transferase; IgG = immunoglobulin G; ASMA = antismooth-muscle antibody.

There is no consensus on the optimal treatment for AIH-PBC overlap. Referral to a specialist is recommended. Therapy should be individualized and is not static. Treatment is often targeted to the predominant component of the disease. Many experts favor a combination therapy of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) plus prednisone and azathioprine, as some studies have shown better outcomes of this regimen compared to UDCA alone. Because of the rapid progression to cirrhosis of untreated AIH, we favor this approach in most cases. Other studies showed that patients with predominant features of PBC may respond to UDCA alone. According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver, UDCA may be tried first in these patients, with prednisone and azathioprine added later if there is an inadequate response after 3 months.

AIH-PBC overlap syndrome has a worse prognosis compared to PBC alone. In addition, AIH-PBC overlap appears to be less responsive to treatment compared to AIH alone, although this did not seem to affect survival.

Autoimmune Hepatitis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Overlap Syndrome

Autoimmune hepatitis-PSC overlap syndrome is characterized by the presence of typical histological features of AIH in combination with cholangiographic or histologic features of PSC. The prevalence of AIH-PSC overlap is 8% to 17%. Children and young adults are more commonly affected. Patients with AIH who have IBD are at increased risk, particularly those with ulcerative colitis.

Autoimmune hepatitis-PSC overlap often occurs in a sequential manner. Typically AIH is diagnosed first and PSC is diagnosed many years later. When patients with AIH are not responsive to immunosuppression, the diagnosis of PSC should be considered.

The diagnosis of AIH-PSC overlap is often made when a patient with AIH is submitted to cholangiography. Patients with AIH-PSC overlap typically have features of AIH such as positive ANA and/or ASMA, hypergammaglobulinaemia, and liver biopsy showing interface hepatitis. In addition, they also have disproportional elevation in alkaline phosphatase and cholangiographic findings of extra and intra hepatic strictures typical of PSC. However a normal cholangiogram does not exclude the diagnosis as typical histologic features of PSC may exist despite normal cholangiographic findings, which is called small duct PSC.

There is insufficient data to recommend cholangiographic screening for all patients with AIH. We suggest screening with MRCP when patients with AIH present with disproportionally elevated alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin or when there is failure to respond to treatment. An exception to this are patients with IBD who are at increased risk for PSC and should be screened with MRCP at the time of AIH diagnosis.

The clinical course of AIH-PSC overlap is similar to that of PSC, with fatigue, jaundice, itching, abdominal pain, and recurrent biliary infections. There are currently no large clinical trials to guide therapy. Treatment for the AIH component with prednisone and azathioprine is commonly used, with lower remission rates compared to isolated AIH. There is currently no medical treatment for PSC, and UDCA has been tried in AIH-PSC with controversial results. The European Association for Study of the Liver recommends treatment with UDCA and corticosteroids. The American Association for Study of Liver Disease suggests treatment with corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive therapy.

The prognosis of AIH-PSC overlap appears to be better than that of PSC alone, but is worse than AIH alone and most patients will progress to liver cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease.

conclusion

Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic inflammatory condition of the liver of unknown etiology. Most patients respond to corticosteroids. The most commonly used treatment regimen is a combination of prednisone and azathioprine. In responsive patients, prognosis is generally good. When there is progression to end-stage liver disease, liver transplantation is an option. Outcomes of liver transplantation are usually good, although recurrence of the disease can occur in the transplanted liver.

Summary

- Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic inflammatory condition of the liver of unknown etiology characterized by elevated liver transaminases and gamma globulins, the presence of autoantibodies and interface hepatitis on histology.

- Autoimmune hepatitis is classified as type 1 and type 2. The disease course differs among the 2 types, but the treatment is the same for both.

- No single test is diagnostic of autoimmune hepatitis. The diagnosis of the disease is made when there is a characteristic clinical scenario, elevation of liver transaminases and gamma globulins, and the presence of autoantibodies. Other causes of liver injury or disease should be excluded.

- Patients with significant disease should be treated. Most patients will respond to treatment.

- The cornerstone of treatment is corticosteroids. Unless otherwise contraindicated, combination of prednisone or budesonide plus azathioprine are the most commonly used treatment regimens. Once in remission for 1 year on combination therapy, prednisone or budesonide can be withdrawn while maintaining azathioprine monotherapy.

- Once in remission for at least 2 years, in the presence of a liver biopsy showing absence of significant inflammation, treatment withdrawal can be attempted although recurrence of disease is common.

- In responsive patients, the prognosis of AIH is generally good, with a 10-year survival of 83.8% to 94%. When progression to end-stage liver disease ensues, liver transplantation is an option.

- In patients with AIH receiving a liver transplant, recurrence of AIH can occur and is usually responsive to treatment with prednisone plus azathioprine. The outcomes for patients with AIH receiving a liver transplant are similar irrespective of recurrence of AIH.

Suggested Reading

- van Gerven NM, Verwer BJ, Witte BI, et al.; Dutch Autoimmune hepatitis STUDY group. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of autoimmune hepatitis in the Netherlands.Scand J Gastroenterol2014; 49:1245–1254.

- Hurlburt KJ, McMahon BJ, Deubner H, Hsu-Trawinski B, Williams JL, Kowdley KV. Prevalence of autoimmune liver disease in Alaska Natives.Am J Gastroenterol2002; 97:2402–2407.

- Czaja AJ, Manns MP, Homburger HA. Frequency and significance of antibodies to liver/kidney microsome type 1 in adults with chronic active hepatitis.Gastroenterology1992; 103;1290–1295.

- Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis.J Hepatol1999; 31:929–938.

- Feld JJ, Dinh H, Arenovich T, Marcus VA, Wanless IR, Heathcote EJ. Autoimmune hepatitis: effect of symptoms and cirrhosis on natural history and outcome.Hepatology2005; 42:53–62.

- Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Reid F, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in childhood: a 20-year experience.Hepatology1997; 25:541–547.

- Muratori L, Cataleta M, Muratori P, Lenzi M, Bianchi FB. Liver/kidney microsomal antibody type 1 and liver cytosol antibody type 1 concentrations in type 2 autoimmune hepatitis.Gut1998; 42:721–726.

- Strettell MD, Donaldson PT, Thomson LJ, et al. Allelic basis for HLA-encoded susceptibility to type 1 autoimmune hepatitis.Gastroenterology1997; 112:2028–2035.

- Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Santrach PJ, Moore SB. Genetic predispositions for the immunological features of chronic liver disease other than autoimmune hepatitis.J Hepatol1996; 24:52–59.

- Doherty DG, Donaldson PT, Underhill JA, et al. Allelic sequence variation in the HLA class II genes and proteins in patients with autoimmune hepatitis.Hepatology1994; 19:609–615.

- Obermayer-Straub P, Perheentupa J, Braun S, et al. Hepatic autoantigens in patients with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy.Gastroenterology2001; 668–677.

- Vento S, Guella L, Mirandola F, et al. Epstein–Barr virus as a trigger for autoimmune hepatitis in susceptible individuals.Lancet1995; 346:608–609.

- Skoog SM, Rivard RE, Batts KP, Smith CI. Autoimmune hepatitis preceded by acute hepatitis A infection.Am J Gastroenterol2002; 97:1568–1569.

- Czaja AJ. Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis.Dig Dis Sci2011; 56:958–976.

- Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, et al. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosis.Hepatology2010; 51:2040–2048.

- Werner M, Prytz H, Ohlsson B, et al. Epidemiology and the initial presentation of autoimmune hepatitis in Sweden: a nationwide study.Scand J Gastroenterol2008; 43:1232–1240.

- Soloway R, Summerskill DM, Baggenstoss AH, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and histological remission of severe chronic active liver disease: a controlled study of treatments and early prognosis.Gastroenterology1972; 63:820–833.

- Murray-Lyon IM, Stern RB, Williams R. Controlled trial of prednisone and azathioprine in active chronic hepatitis.Lancet1973; 1:735–737.

- Cook GC, Mulligan R, Sherlock S. Controlled prospective trial of corticosteroid therapy in active chronic hepatitis.Q J Med1971; 40:159–185.

- Roberts SK, Therneau TM, Czaja AJ. Prognosis of histological cirrhosis in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis.Gastroenterology1996; 110:848–857.

- Bridoux-Henno L, Maggiore G, Johanet C, et al. Features and outcome of autoimmune hepatitis type 2 presenting with isolated positivity for anti-liver cytosol antibody.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol2004; 2:825–830.

- Zauli D, Ghetti S, Grassi A, et al. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in type 1 and 2 autoimmune hepatitis.Hepatology1997; 25:1105–1107.

- O'Brien C, Joshi S, Feld JJ, Guindi M, Dienes HP, Heathcote EJ. Long-term follow-up of antimitochondrial antibody-positive autoimmune hepatitis.Hepatology2008; 48:550–556.

- Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis.Hepatology2010; 51:2193–2213.

- Perdigoto R, Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ. Frequency and significance of chronic ulcerative colitis in severe corticosteroid-treated autoimmune hepatitis.J Hepatol1992; 14:325–331.

- Summerskill WH, Korman MG, Ammon HV, Baggenstoss AH. Prednisone for chronic active liver disease: dose titration, standard dose, and combination with azathioprine compared.Gut1975; 16:876–883.

- Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis.N Engl J Med1995; 333:958–963.

- Manns MP, Woynarowski M, Kreisel W, et al; European AIH-BUC-Study Group. Budesonide induces remission more effectively than prednisone in a controlled trial of patients with autoimmune hepatitis.Gastroenterology2010; 139:1198–1206.

- Czaja AJ. Rapidity of treatment response and outcome in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis.J Hepatol2009; 51:161–167.

- Czaja AJ, Menon KV, Carpenter HA. Sustained remission after corticosteroid therapy for type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: a retrospective analysis.Hepatology2002; 35:890–897.

- Czaja AJ, Wolf AM, Baggenstoss AH. Laboratory assessment of severe chronic active liver disease during and after corticosteroid therapy: correlation of serum transaminase and gamma globulin levels with histologic features.Gastroenterology1981; 80:687–692.

- van Gerven NM, Verwer BJ, Witte BI, et al; Dutch Autoimmune Hepatitis Working Group. Relapse is almost universal after withdrawal of immunosuppressive medication in patients with autoimmune hepatitis in remission.J Hepatol2013; 58:141–147.

- Kanzler S, Gerken G, Löhr H, Galle PR, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Lohse AW. Duration of immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune hepatitis.J Hepatol2001; 34:354–355.

- Hartl J, Ehlken H, Weiler-Normann C, et al. Patient selection based on treatment duration and liver biochemistry increases success rates after treatment withdrawal in autoimmune hepatitis.J Hepatol2015; 62:642–646.

- Dhaliwal HK, Hoeroldt BS, Dube AK, et al. Long-term prognostic significance of persisting histological activity despite biochemical remission in autoimmune hepatitis.Am J Gastroenterol. Published online: May 26, 2015 (doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.139).

- Lüth S, Herkel J, Kanzler S, et al. Serologic markers compared with liver biopsy for monitoring disease activity in autoimmune hepatitis.J Clin Gastroenterol2008; 42:926–930.

- Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Histological features associated with relapse after corticosteroid withdrawal in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis.Liver Int2003; 23:116–123.

- Czaja AJ. Current and prospective pharmacotherapy for autoimmune hepatitis.Expert Opin Pharmacother2014; 15:1715–1736.

- Montano-Loza AJ, Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ. Features associated with treatment failure in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis and predictive value of the model of end-stage liver disease.Hepatology2007; 46:1138–1145.

- Reich DJ, Fiel I, Guarrera JV, et al. Liver transplantation for autoimmune hepatitis.Hepatology2000; 32:693–700.

- Molmenti EP, Netto GJ, Murray NG, et al. Incidence and recurrence of autoimmune/alloimmune hepatitis in liver transplant recipients.Liver Transpl2002; 8:519–526.

- Gonzalez-Koch A, Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, et al. Recurrent autoimmune hepatitis after orthotopic liver transplantation.Liver Transpl2001; 7:302–310.

- Aqel BA, Machicao V, Rosser B, Satyanarayana R, Harnois DM, Dickson RC. Efficacy of tacrolimus in the treatment of steroid refractory autoimmune hepatitis.J Clin Gastroenterol2004; 38:805–809.

- Inductivo-Yu I, Adams A, Gish RG, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in autoimmune hepatitis patients not responsive or intolerant to standard immunosuppressive therapy.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol2007; 5:799–802.

- Weiler-Normann C, Wiegard C, Schramm C, Lohse AW. A case of difficult-to-treat autoimmune hepatitis successfully managed by TNF-alpha blockade.Am J Gastroenterol2009; 104:2877–2878.

- Burak KW, Swain MG, Santodomino-Garzon T, et al. Rituximab for the treatment of patients with autoimmune hepatitis who are refractory or intolerant to standard therapy.Can J Gastroenterol2013; 27:273–280.

- Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid as adjunctive therapy for problematic type1 autoimmune hepatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled treatment trial.Hepatology1999; 30:1381–1386.

- Coelho J, Beaugerie L, Colombel JF, et al. Pregnancy outcome in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with thiopurines: cohort from the CESAME Study.Gut2011; 60:198–203.

- Westbrook RH, Yeoman AD, Kriese S, Heneghan MA. Outcomes of pregnancy in women with autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun 2012; 38:J239–J244.

- Schramm C, Herkel J, Beuers U, Kanzler S, Galle PR, Lohse AW. Pregnancy in autoimmune hepatitis: outcome and risk factors.Am J Gastroenterol2006; 101:556–560.

- Angelberger S, Reinisch W, Messerschmidt A, et al. Long-term follow-up of babies exposed to azathioprine in utero and via breastfeeding.J Crohns Colitis2011; 5:95–100.

- Chazouillères O, Wendum D, Serfaty L, Montembault S, Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome: clinical features and response to therapy.Hepatology1998; 28:296–301.

- Joshi S, Cauch-Dudek K, Wanless IR, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis with additional features of autoimmune hepatitis: response to therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid.Hepatology2002; 35:409–413.

- Lohse AW, zum Büschenfelde KH, Franz B, Kanzler S, Gerken G, Dienes HP. Characterization of the overlap syndrome of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and autoimmune hepatitis: evidence for it being a hepatitic form of PBC in genetically susceptible individuals.Hepatology1999; 29:1078–1084.

- Poupon R, Chazouillères O, Corpechot C, Chrétien Y. Development of autoimmune hepatitis in patients with typical primary biliary cirrhosis.Hepatology2006; 44:85–90.

- Boberg KM, Chapman RW, Hirschfield GM, Lohse AW, Manns MP, Schrumpf E; International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Overlap syndromes: the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) position statement on a controversial issue.J Hepatol2011; 54:374–385.

- Silveira MG, Talwalkar JA, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Overlap of autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: long-term outcomes.Am J Gastroenterol2007; 102:1244–1250.

- Al-Chalabi T, Portmann BC, Bernal W, McFarlane IG, Heneghan MA. Autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndromes: an evaluation of treatment response, long-term outcome and survival.Aliment Pharmacol Ther2008; 28:209–220.

- Kaya M, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Overlap of autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: an evaluation of a modified scoring system.J Hepatol2000; 33:537–542.

- Floreani A, Rizzotto ER, Ferrara F, et al. Clinical course and outcome of autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome.Am J Gastroenterol2005; 100:1516–1522.

- van Buuren HR, van Hoogstraten HJE, Terkivatan T, Schalm SW, Vleggaar FP. High prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis among patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.J Hepatol2000; 33:543–548.

- Olsson R, Glaumann H, Almer S, et al. High prevalence of small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis among patients with overlapping autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis.Eur J Intern Med2009; 20:190–196.

- Abdo AA, Bain VG, Kichian K, Lee SS. Evolution of autoimmune hepatitis to primary sclerosing cholangitis: a sequential syndrome.Hepatology2002; 36:1393–1399.

- Lewin M, Vilgrain V, Ozenne V, et al. Prevalence of sclerosing cholangitis in adults with autoimmune hepatitis: a prospective magnetic resonance imaging and histological study.Hepatology2009; 50:528–537.

- Lüth S, Kanzler S, Frenzel C, et al. Characteristics and long-term prognosis of the autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome.J Clin Gastroenterol2009; 43:75–80.

- Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis.Hepatology2010; 51:660–678.

- Boberg KM, Egeland T, Schrumpf E. Long-term effect of corticosteroid treatment in primary sclerosing cholangitis patients.Scand J Gastroenterol2003; 38:991–995.