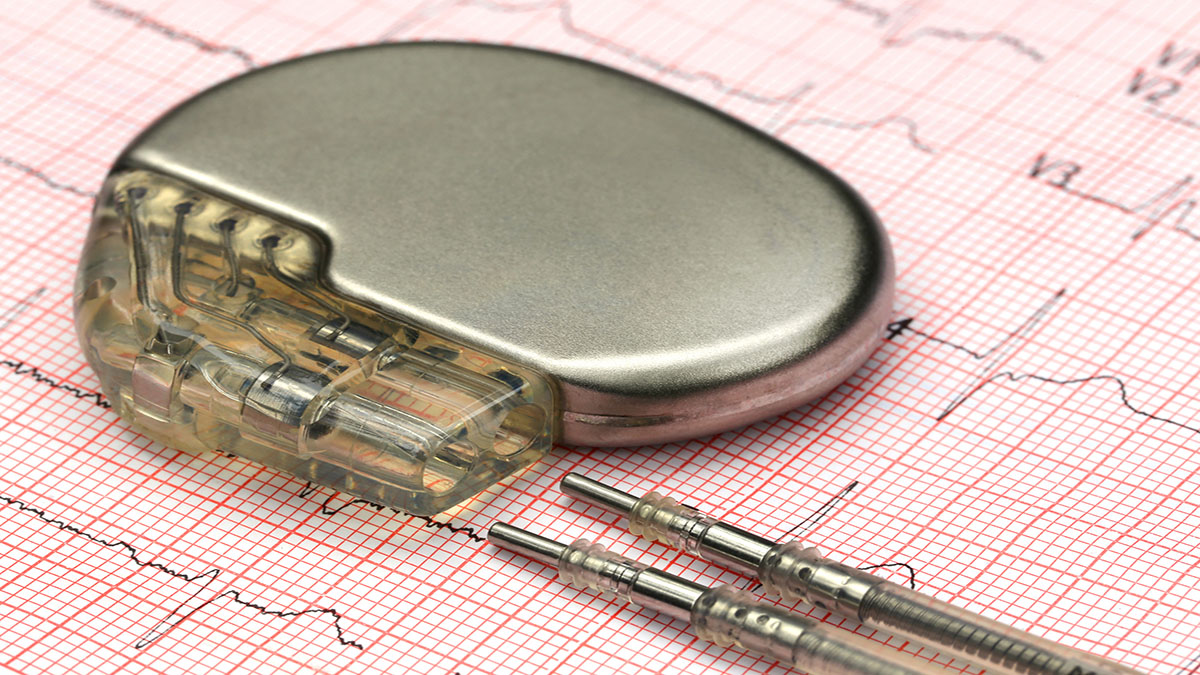

Insights into Allergy and Implanted Cardiac Devices: Part 1 - Diagnosis and Testing

Patients with allergies to certain metals and compounds can make safely treating them challenging. Dr. Tom Callahan and Dr. Bruce Wilkoff speak with Dr. John Anthony, Dermatology, and Dr. James Taylor, Clinical Professor of Dermatology, regarding diagnosis and testing for patients with suspected allergies to compounds in implantable cardiac devices.

Interested in learning more about lead management? visit: https://leadconnection.org

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Buzzsprout | Spotify

Insights into Allergy and Implanted Cardiac Devices: Part 1 - Diagnosis and Testing

Podcast Transcript

Announcer:

Welcome to Cleveland's Clinic Cardiac Consult, brought to you by the Sydell and Arnold Miller Family Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Institute at Cleveland Clinic.

Thomas Callahan, MD:

Welcome to the LEADConnection podcast where we talk about everything related to lead management. I'm Tom Callahan and I'm joined by Dr. Bruce Wilkoff, one of the founders of LEADConnection, Dr. John Anthony who's section head of Occupational and Contact Dermatology at Cleveland Clinic, and Dr. Jim Taylor, Clinical Professor of Dermatology at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. Welcome everyone.

John Anthony, MD:

Thank you.

James Taylor, MD:

Thank you.

Thomas Callahan, MD:

We've got an exciting topic today. We're going to talk about allergy as it relates to implantable cardiac devices. I think I'll start out with just a question about allergy to medical devices in general. Do we have a sense of how common this is?

James Taylor, MD:

I think it's relatively uncommon. There are certain devices where we see it more frequently, perhaps with orthopaedic devices where we've been dealing with the issue for probably more than 40 years. Static orthopaedic devices like screws and rods are perhaps more likely to produce reactions than dynamic ones, the total joints and so forth. The other things that we've seen related to that would be Nuss bars in pediatric thoracic surgery. In some cases, cardiovascular devices such as Amplatzer's endovascular devices for PFO and ASD occlusion. John, I don't know if you think of others.

John Anthony, MD:

One of the best studied is probably the Nuss bars. I think our thinking has taken an evolution. There was a period of time where, because most of those were steel implants, a lot of patch testing was being done because the titanium alternative was very expensive and hard to obtain. And as time has gone on, there's been a shift, I think, in practice so that the majority of that's titanium that's being implanted these days. And so, the impetus to patch test and to identify metal allergy has shifted away as the technology has changed.

Thomas Callahan, MD:

Interesting.

Bruce Wilkoff, MD:

Devices, pacemakers and defibrillators are titanium. What's your thought about titanium? If it doesn't happen or, tell me what you think.

John Anthony, MD:

I think it can happen. I think that our consensus is that titanium allergy is very rare, and I think it's quite difficult to identify with patch testing. The allergens or the haptens are difficult to read and a little unpredictable. I don't know if Jim has some thoughts on that, but it's very uncommon for me to find a titanium allergy. It's more likely that the tests are a little more irritant. So, they're hard to interpret sometimes, but we do think that titanium is, while it can be a real thing, it's uncommon. What do you think, Jim?

James Taylor, MD:

Yes, I agree. The issue is testing for it. If you look in the reports, there are isolated reports of titanium allergy. The conclusions for how to test are that patch testing is helpful but not definitive. We don't have the appropriate salts to patch test with. Other test methods such as the in vitro lymphocyte transformation test is not that helpful at times and may be oversensitive. Again, there are very isolated reports of cases where they've, with the pacemakers, coated them with PTFE, or in one case they coated it with gold. That seemed to help the case where they thought that there was a titanium allergy. But again, it's difficult to prove and identify. Plus, there are other potential components of pacemakers and ICDs that can be allergenic occasionally. I started out with epoxy resin, but to my understanding, that's not used much anymore, if at all. Again, there are isolated reports of reactions to other components of pacemakers, but again, it's generally relatively uncommon. There are isolated reports of isolated reactions over the implant itself or over the pacemaker, and then a few cases of, for instance, disseminated or generalized dermatitis.

Thomas Callahan, MD:

That goes to my next question about the other components. The devices themselves are mostly titanium or at least the outer surfaces. But how about the leads with the components of the lead and the lead insulation? I don't know if that's something that we commonly see allergies to.

John Anthony, MD:

In my experience, I've seen it probably once, we still must report this, I think. One of the companies provided me with samples of components of the pacemaker. The patient actually reacted to two of the silicones, which I understand were concentrated in the yoke that was attached to the generator. So that was a real challenge. She seemed to react reasonably strongly. I think Jim, you may have seen that patient with me. And so, we concluded that she had a silicone allergy, which is extremely unusual, I think. But this is actually a question that I had. So, a lot of the reports presume that an intolerance to the device is due to hypersensitivity, but I also think that a lot of the devices are removed for punitive infection, because the inflammation looks similar. And I don't think I know how to tell the difference. What clues do you use to help decide whether you think it's hypersensitivity or true infection? That's a real problem, I think.

Bruce Wilkoff, MD:

I thought you were going to tell us. Wow, that is tough. I mean, inflammation is inflammation, as near as I can tell. And whether it's mechanical or it's allergy or infection, I don't know that we can tell the difference. We've seen everything from what we think is allergy, although not very commonly to often infection too, we've seen the superimposition of a tumor that looks a little like both and which can be anything from skin to what's under the skin to causing tumors. So, the differential diagnosis, there are rare things, but rare things do happen, and we have to be very careful about that. So, you're telling me you don't have the magic bullet as to telling the difference between one kind of pathogen and infection versus an allergen type thing?

John Anthony, MD:

That is a real challenge and a problem. I think that usually when I'm seeing patients, it's usually after the failure of a couple of different implantations. So, infection is presumed, the device is removed, a second device is implanted. Subsequently they have a similar problem. And so, there's either a patient factor that incites infection or that makes them prone to infection or we've been dealing with hypersensitivity. That's usually when I'm seeing the patients. I haven't, for the implanted defibrillators and pacemakers, really done too much pre-implantation testing. Is that because they're mostly done kind of urgently or is that, how planned out are those usually?

Bruce Wilkoff, MD:

Tom, either of us could talk about it. What happens is that we consider it, I mean we put a lot of these devices in. And the rate of infection for instance, is in the order of primary implants of 0.5 percent and it's extended over half of that happens in the first year. Half of it happens after the first year. So, it's really difficult to tell. So, unless somebody is really making noise saying that they have a problem, let's say the usual problem would be they have a nickel allergy, which is kind of common. And then we might ask, but I'd say virtually never ask for. We just work through it and the few that come out at the end are the ones that problem patients that we see together.

James Taylor, MD:

And it's usually the, well in some cases, and often more recently, the Infectious Disease docs at the Clinic who have gotten involved in the case. And in the last case that I saw actually suggested that you all consult us for patch testing because they couldn't identify a specific infectious cause.

Thomas Callahan, MD:

So just staying on that difficulty in differentiating between an infection and a reaction to the components. Is there anything in the time course that might help? I mean, do these allergic reactions happen very early? Do they happen anytime during the sort of lifetime of the implanted device?

James Taylor, MD:

They can occur almost any time. One review I was looking at mentioned anywhere from two days to several years. So, it's not from my standpoint, I don't think the timing is necessarily that helpful. The other thing that comes up is again, other components so that when we see the patient, we try to at least, we have standard materials to test for. But there are new ones and as John mentioned, some of the companies provide us with pieces and parts to patch test with. And in the case of metal discs for nickel, it's basically suggested that that's probably not that helpful. And you can get false negative reactions, you could also get false positive reactions over read as pressure. So, we generally test with individual metal salts, which are the most reliable for identifying at least metal allergy. But when you get into the other components, then you may need the components that the manufacturer provides, such as the silicone that John mentioned, polyurethane, you've got a bunch of other components now that some of the electrodes are platinum iridium, and I guess some of the leads I was reading in one case were polymethylmethacrylate, so forth.

Bruce Wilkoff, MD:

Yeah, the polymethylmethacrylate is usually the header that's attached to the titanium can. Then there's the silicone that usually seals between the two that you would see. And then there are the metals that are in the leads themselves have a little bit of nickel, but not very much as they're combined into a wire that's inside the plastic, silicone or polyurethane. You mentioned orthopaedic devices, once they got away from steel, do you still have that kind of problem you're seeing? Do you still see the allergies to that, and would give us an idea of how frequent titanium might be an issue here?

James Taylor, MD:

We still see some allergies, and again, the experience is somewhat operator dependent. In some cases, if the patient comes and tells the orthopaedic surgeon that they're nickel allergic, in at least one case I'm familiar with, the physician will just use an oxinium device for instance, or perhaps a titanium one rather than doing testing. And I think in some cases with your devices, with the pacemakers and ICDs, this is basically what's happened. They thought that they couldn't identify an infection and so then they coated it with PTFE or some related envelope. And the most recent case I think that I've seen, and maybe John has too, is you're now having, you have a minocycline impregnated and I believe is their Rifampin in there also?

Bruce Wilkoff, MD:

That's right.

James Taylor, MD:

And in the one case, the most recent one, I think one of the most recent ones I saw, we couldn't identify. We identified topical antibiotics as a cause, as an allergen, a neomycin bacitracin and so forth, but we couldn't identify the envelope as the cause. But again, in my conclusions to you, I said, well, you perhaps might want to consider a different envelope even though we couldn't prove allergies. So again, I don't know, John, do you have any?

John Anthony, MD:

I think that it's so difficult to get reliable data because sometimes the patient's self-reported metal allergy alters the selection of the device. Now there's some particular situations, especially some of the robotic device implantations, where the choices aren't quite as widespread, so some of the patients are still getting implanted despite that history. But I did want to, if I could circle back to the question about discerning hypersensitivity versus infection, and I don't know that we have, there aren't really great criterion, but my instinct I think would be to say that in situations where you see an eczematous dermatitis, so a rash as opposed to just heat and pain and discomfort, so a rash localized over the implant site would either suggest some for operative, especially in the short term, in that two week, four week time period, they were either allergic to a prep or rarely, I guess the suture material, that's really rare. Or maybe a steri-strip, if that's used, sometimes the benzoin or even the plastic that's sometimes used in the fields. And then if it's not really immediate but delayed and overlying the implant can, we use that as sort of a suspicious criterion for orthopaedic implants. So, I would assume that that would happen. So, if you could discern more rash, poison ivy-ish kind of look versus just pain and swelling, that might be a symptom. And then in those rare cases where you see a diffuse eczematous rash, eczema-like, that would also lead me to think maybe a systemic reaction to the metal. Also extremely rare, but those are really the only criteria I can think of that would help me in that acute situation. What do you think about that, Jim? We don't have consensus criteria, no.

James Taylor, MD:

No, that's true. Again, in addition to what John said, there are other entities that have been reported, and I've seen it once or twice with orthopaedic implants, reticular telangiectatic erythema, or it's sometimes called pressure erythema, pressure dermatitis. There was a mid-dermal elastolysis that was reported. And then the importance of potential for suture allergy and the peri procedure, things that John mentioned such as benzoin, it might be used as an adhesive, topical antibiotics that then can produce a dermatitis that has nothing directly to do with the implant. Other dermatoses, drug eruptions. Those are the main things that we end up considering in a differential diagnosis and seeing. And when we evaluate a patient, consider those factors in addition to the implant and whether they've had previous. So, the one question we always ask is, have you had a previous implant, and did you have any reactions? So, some of the patients with pacemakers have had orthopaedic devices, so that may or may not be helpful in the evaluation of them.

Thomas Callahan, MD:

So, what I'm getting is this is a really challenging problem. I mean, it's very difficult to predict who's going to have these reactions, and then it's very difficult to confirm the diagnosis. Well, this was a great conversation. I want to thank both of you, Dr. Taylor and Dr. Anthony for joining us. Really insightful. Thank you so much for your time and insights.

John Anthony, MD:

Thank you so much. I appreciate the opportunity.

James Taylor, MD:

Likewise. Thank you, Tom.

Thomas Callahan, MD:

All right. Until next time.

Bruce Wilkoff, MD:

Bye-bye.

Announcer:

Thank you for listening. We hope you enjoyed the podcast. We welcome your comments and feedback. Please contact us at heart@ccf.org. Like what you heard? Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts or listen at clevelandclinic.org /cardiacconsultpodcast.

Cardiac Consult

A Cleveland Clinic podcast exploring heart, vascular and thoracic topics of interest to healthcare providers: medical and surgical treatments, diagnostic testing, medical conditions, and research, technology and practice issues.