Anxiety and depression are common co-morbidities for persons with multiple sclerosis (PwMS) which significantly impact quality of life and overall well-being. Cleveland Clinic Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis’ behavioral medicine approach to addressing anxiety and depression is specialized to assess common symptoms of anxiety and depression along with multiple sclerosis-specific mood concerns. The behavioral medicine team addresses symptoms of anxiety and depression utilizing evidence-based treatments targeted at decreasing depression and anxiety and increasing effective coping and stress management skills. Symptoms of both depression and anxiety can worsen neurological symptoms which makes treating mental health concerns in PwMS essential to the comprehensive management of multiple sclerosis1, 2.

What is the prevalence rate of anxiety and depression in the multiple sclerosis population?

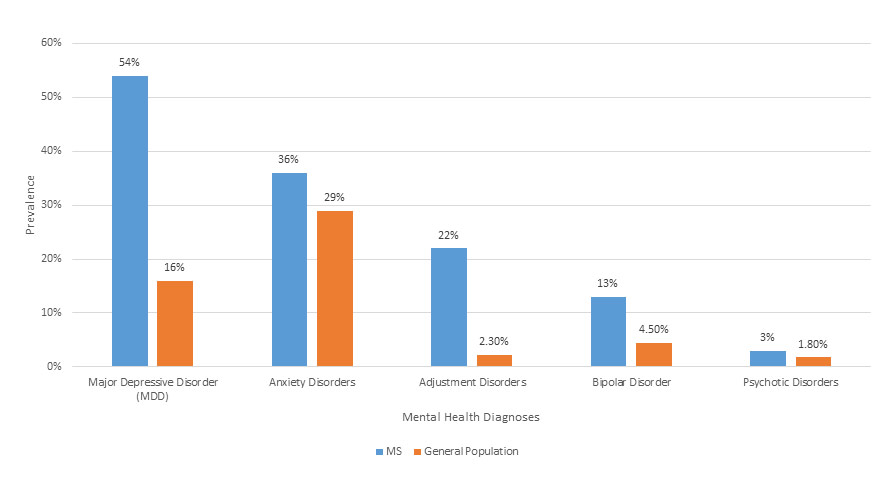

Symptoms of anxiety and depression are common among the multiple sclerosis (MS) patient population, and these symptoms occur at a significantly elevated rates compared to both the general population, and other neurological conditions3, 4. In fact, individuals living with MS are 3-4x as likely to develop a mood disorder compared to the general population (Figure).

More specifically, the prevalence of depressive disorders in the MS population (36-54%) is more than double that of the general population (16%). Similarly, the prevalence of anxiety disorders in the MS population is 36%, compared to 29% in the general population. Elevated prevalence of mood disorders in the MS population also include adjustment disorders (22% vs. 0.2-2.3% in general population) and bipolar disorder (13% vs. 1-4.5% in general population), while prevalence of pseudobulbar affect ranges (6.5-46.2%) 4.

Risk Factors for Anxiety/Depression in PwMS

PwMS are at a higher risk for anxiety and/or depressive symptoms for several reasons. For example, times of transition (e.g., initial diagnosis, accumulation of disability, change in functioning, and transition out of work), pathophysiology (e.g., inflammatory demyelinating lesions and neurodegenerative changes), and effects of medications can all lead to the development of mood symptoms2, 4. In addition, the ways in which PwMS cope can be an indicator of whether clinically significant mood symptoms occur. Factors that may influence poor coping include: tendency to avoid, less positive attitude, and disengagement from social support and treatment resources. Factors that may influence effective coping include engagement with sources of support, engagement in activities previously enjoyed (even if activities now look different), and active participation in treatment planning. Furthermore, tendencies to use avoidant strategies were associated with increased risk of mood symptoms3. Therefore, providing opportunities to develop effective coping skills may mitigate this risk for our patient population.

In addition, perceived support plays a large role in one’s adjustment to living with MS. Both practical and emotional support from others, as well as the perception that others were available to provide support, significantly reduce risk of mood symptoms. Therefore, lack of support may be an additional risk factor in adjustment to diagnosis and the experience of mood symptoms in individuals living with MS5.

How do we screen for anxiety and depression in our patient population?

Regular screening for mood disorders is a key element of a comprehensive treatment model for PwMS. While those living with MS are at significantly higher risk to experience mood disorders, efficacious treatment is available6. By screening for mood disorders we are able to offer early intervention and monitoring of symptoms throughout treatment, both of which can assist in significantly reducing mood symptoms6. At the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis, PwMS complete subjective measures of mood including: the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the Neurological Quality of Life (Neuro-QoL) Anxiety scale, and the Neuro-QoL Depression scale Scales used depend on the type of visit (behavioral medicine or neurology) as described below.

Behavioral Medicine Screening

The GAD-7 is a validated scale using 7 criteria for anxiety, each rated on a scale from 0-3, while the PHQ-9 is a validated scale using 9 criteria for depression, each rated on a scale from 0-37. Each of these measures can be completed prior to a visit via MyChart pre-check in, via tablet within the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis, or during session with a provider via the “BH Measures” tab. A paper version can be provided to patients to allow them to view questions and answer appropriately. To track progress over time, patients are prompted to complete these measures when completing pre-check in requirements prior to meeting with their providers. While measures are often completed by patients prior to each visit, the check-in system triggers the PHQ-9 as a requirement for the check-in process every 28 days.

Neurology Screening

The Neuro-QoL is a validated set of brief measures of health related quality of life8. The Neuro-QoL anxiety scale is comprised of 21 items, each rated on a scale from 1-5, while the Neuro-QoL depression scale is comprised of 24 items, each rated on a scale from 1-5. At the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis, the anxiety and depression scales of the Neuro-QoL are collected within the MS Performance Test (MSPT). The MSPT comprises a battery of neuroperformance tests and quantitative patient-reported outcome measures administered using a tablet-based application developed at Cleveland Clinic. These measures are completed prior to each visit with a neurology provider.

Interpretation

To determine significance of symptoms, each of these scales have specific cut-off scores. For the GAD-7, raw scores can range from 0-21 and are categorized into minimal (0-4), mild (5-9), moderate (10-14), and severe (> 15)7anxious symptoms. For the PHQ-9, raw scores can range from 0-27 and are categorized into minimal (0-4), mild (5-9), moderate (10-14), and moderately severe (15-19), and severe (> 20)7depressive symptoms. The Neuro-QoL converts raw scores to T-scores, with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 109. A higher T-score represents higher levels of the concept being measured. For the anxiety and depression scales, a T-score of 60 would represent one standard deviation worse than the averaged reference population9. Therefore, higher T-scores represent higher endorsement of symptoms consistent with anxiety and depression, and lower T-scores represent lesser endorsement. While clinically meaningful change scores have been studied for specific Neuro-QoL scales, authors suggest a combination of change in scores and clinical judgement should be utilized to estimate important change10.

Suicide Screening

Within the PHQ-9, there is a question assessing suicidal ideation. If suicidality is endorsed when a patient completes the PHQ-9, the system will trigger additional screening via the Cleveland Suicide Screen. The Cleveland Suicide Screen was developed by Cleveland Clinic, utilizing the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale as a reference, and includes two questions aimed at assessing discouragement and suicidal ideation11. A positive suicide screen will also trigger a “Best Practice Advisory” within the medical chart, meaning upon opening of the patient’s chart, the provider will be made aware for further screening and safety planning.

Common Symptoms/Presentations/Diagnoses

Anxiety

When considering symptoms of anxiety, it is important to assess content of worry (generalized vs. specific), history of symptoms, significant life stressors, and use of coping skills. Significant stressors, such as a new medical diagnoses, can cause recurrence of previously present symptoms, which may point to a generalized anxiety disorder, or a significant emotional reaction to diagnosis, which would more likely lend itself to a diagnosis of adjustment disorder with anxious mood12.

Depression

While it is well-known that mood symptoms are common in the MS population, it is important for us to thoroughly assess the presentation of each patient. Depression may be premorbid, a symptom of MS, or a reaction to diagnosis and management2. For example, the most common diagnoses we tend to make at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis include major depressive disorder (history of symptoms consistent with depression), mood disorder due to MS (symptoms associated with diagnosis) and adjustment disorder with depressed mood (result of diagnosis/management)12. A thorough assessment of history, coping skills, and current functioning is imperative to providing an accurate diagnosis.

How is quality of life impacted by anxiety and depression?

Mood symptoms, including anxiety and depression, are important predictors of overall quality of life in PwMS13. Quality of life is often broken down into multiple domains, such as areas of functioning (physical, financial, social, affective) and experience of medical problems. Mental health co-morbidities, including depression and anxiety, impact PwMS quality of life more significantly as compared to the general population as well as other chronic medical conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease 14, 15.

Reasons to Intervene

It is important to note that a certain degree of reactivity when receiving a new diagnosis is normal. However, if daily functioning (i.e., at home, work, in family roles) becomes impacted, this may be an indication intervention may be appropriate.

While we have made significant strides in management of MS, it is imperative we continue to focus on the importance of mental health15. Mood symptoms contribute to the increased experience of physiological symptoms of MS, such as pain and fatigue, which increase disease burden3, 4, 17. By decreasing the experience of symptoms of depression and anxiety, there is evidence that not only will quality of life increase, but management of physical symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance) and adherence to medical regimens will also be positively impacted16. This suggests interdisciplinary care that emphasizes both physical and mental health offers significant benefits PwMS. Those who are most likely to receive referral to behavioral medicine services are younger patients and those presenting with more severe depressive symptoms18. However, there are many benefits to early intervention, such as prevention of worsening mood symptoms and the development of effective coping skills.

Efficacy of Treatment and Management of Anxiety and Depression in MS

Stress Management

Stress management interventions include psychoeducation and behavioral techniques aimed at reducing the physiological impact of stress in both the short and long-term. Techniques such as diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, body scans, and mindfulness are taught in session, along with establishing grounds for regular practice in daily life. Often times, exercises are coupled with the monitoring of physiological measures (e.g., heart rate, breaths per minute) to observe one’s physiological response to the intervention and provide positive feedback for efficacy of the exercise.

There is a large body of literature supporting the use of stress management interventions to assist in effectively managing life stressors and decreasing emotional distress19, 20. In addition, it is important to note that the effective use of stress management skills can also positively impact physical symptoms associated with MS17, 20.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a modality of psychotherapy in which both behavioral (i.e., scheduling pleasant activities--even if those activities look different than they previously did) and cognitive (i.e., evaluating thoughts, and processing emotional reactions to diagnosis) interventions assist in decreasing symptoms of anxiety and depression and increasing overall quality of life 22, 23.

CBT has been well supported within the literature and has been shown to be effective in significantly reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression in PwMS24, 25. More recently, this modality has also established efficacy in less traditional formats. Traditionally, individual CBT sessions would likely take place in person on a regular basis. However, trials of virtual and telephone based CBT have demonstrated significant reduction in mood symptoms in PwMS and increased quality of life26.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Depression and Anxiety

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is an evidence based therapy modality in which the focus of intervention is aimed on acceptance, improving psychological flexibility, and living life in alignment with one’s values. A treatment goal within ACT is to promote resiliency and flexibility in managing emotional responses to situations in which one has limited control, such as development and management of a chronic medical condition26.

ACT is an appropriate psychotherapeutic intervention in individuals adjusting to MS diagnosis, as the hallmarks of this modality promote resilience. ACT conducted in both individual and group settings is efficacious in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety, and increasing acceptance of diagnosis27, 28.

Group Therapy

Group psychotherapy is an efficacious manner of delivering services to a group of individuals rather than individually. Group participants are screened prior to entering a psychotherapy group to ensure appropriateness for partaking in group therapy. We offer multiple support groups to meet the needs of our PwMS, including a weekly MS support group, monthly young professionals support group, monthly men’s support group, and monthly caregiver support group. These groups are meant to be a space for individuals to discuss recent life events, share challenges and accomplishments, and connect with others who have shared similar experiences and can provide meaningful insight and support. Each of our groups are facilitated by a licensed health psychologist and health psychology fellow, who assist in guiding conversation and collecting/distributing resources that are discussed in group as appropriate.

Engagement in group therapy focused on sharing experiences and support with others can bring validity to one’s experiences and provide a strong sense of community. The group environment can foster a strong sense of support and increase adjustment to diagnosis29. Adjustment to diagnosis is important in quality of life, as this is an important time for developing coping skills and establishing a source of support. Another significant benefit to this modality is the ability for one provider to engage with multiple individuals during one session, creating greater access to psychological services.

Multidisciplinary Symptom Management

There are times in which behavioral medicine intervention needs to be complimented with medication to manage mood concerns. If mood symptoms warrant additional intervention the behavioral medicine team will work alongside neurology providers to determine if a medication trial is appropriate, or if the patient may benefit most from consultation with psychiatry providers. If additional stressors such as work or transportation are playing a role, the behavioral medicine team will refer to social work for their expertise in providing efficacious resources and guidance. The multidisciplinary approach utilized within the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis ensures the unique needs of each and every patient are addressed.

Typically, a behavioral medicine consultation is placed by the patient’s medical care team. During consultation with behavioral medicine need for additional resources (e.g., social work, medication management for mood with medical team, psychiatry) are identified. To assist in facilitating access to these resources, providers often communicate via secure messaging. Necessary referrals or orders are then placed as needed.

Considerations

When considering efficacious mental health intervention it is important to develop a treatment plan in collaboration with the patient. During initial evaluation, our goal is to come to a consensus on a treatment plan moving forward, so by the end of session each patient knows when they will be seen again and other services that may also provide assistance in reaching their goals. Depending on presenting concerns, plans for treatment will be individualized for each patient

Figure. Mental Health Prevalence Rates in MS vs. General Population4.

References

- Artemiadis, A. K., Anagnostouli, M. C., & Alexopoulos, E. C. (2011). Stress as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis onset or relapse: A systematic review. Neuroepidemiology, 36(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1159/000323953

- Sparaco, M., Miele, G., Lavorgna, L., Abbadessa, G., & Bonavita, S. (2022). Association between relapses, stress, and depression in people with multiple sclerosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurological sciences: official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology, 43(5), 2935–2942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-05917-z

- Butler, E., Matcham, F., & Chalder, T. (2016). A systematic review of anxiety amongst people with multiple sclerosis. MS and related disorders, 10, 145–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2016.10.003

- Minden, S. L., Feinstein, A., Kalb, R. C., Miller, D., Mohr, D. C., Patten, S. B., Bever, C., Jr, Schiffer, R. B., Gronseth, G. S., Narayanaswami, P., & Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology (2014). Evidence-based guideline: Assessment and management of psychiatric disorders in individuals with multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 82(2), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000013

- Uccelli, M. M., Tacchino, A., Pedullà, L., Bragadin, M. M., Battaglia, M. A., Brichetto, G., & Ponzio, M. (2022). Predictors of mood disorders in parents with multiple sclerosis: The role of disability level, coping techniques, and perceived social support. International journal of MS care, 24(5), 224–229. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2021-101

- Goldman Consensus Group (2005). The Goldman Consensus statement on depression in multiple sclerosis. MS (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England), 11(3), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458505ms1162oa

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2010). The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. General hospital psychiatry, 32(4), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006

- Cella, D., Lai, J. S., Nowinski, C. J., Victorson, D., Peterman, A., Miller, D., Bethoux, F., Heinemann, A., Rubin, S., Cavazos, J. E., Reder, A. T., Sufit, R., Simuni, T., Holmes, G. L., Siderowf, A., Wojna, V., Bode, R., McKinney, N., Podrabsky, T., Wortman, K., … Moy, C. (2012). Neuro-QOL: Brief measures of health-related quality of life for clinical research in neurology. Neurology, 78(23), 1860–1867. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f744

- Neuro-QoL Scoring Guide. Published July, 2022. Neuro-QOL Scoring Manual 08July2021.pdf (healthmeasures.net)

- Meaningful Change in Neuro-QoL. Published 2022. Meaningful Change (healthmeasures.net)

- Viguera, A. C., Milano, N., Laurel, R., Thompson, N. R., Griffith, S. D., Baldessarini, R. J., & Katzan, I. L. (2015). Comparison of electronic screening for suicidal risk with the patient health questionnaire item 9 and the columbia suicide severity rating scale in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Psychosomatics, 56(5), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2015.04.005

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders(5th ed.).

- Sehanovic, A., Kunic, S., Ibrahimagic, O. C., Smajlovic, D., Tupkovic, E., Mehicevic, A., & Zoletic, E. (2020). Contributing factors to the quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Medical archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina), 74(5), 368–373. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2020.74.368-373

- Berrigan, L. I., Fisk, J. D., Patten, S. B., Tremlett, H., Wolfson, C., Warren, S., Fiest, K. M., McKay, K. A., Marrie, R. A., & CIHR Team in the Epidemiology and Impact of Comorbidity on MS (ECoMS) (2016). Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Direct and indirect effects of comorbidity. Neurology, 86(15), 1417–1424. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002564

- Rudick, R. A., Miller, D., Clough, J. D., Gragg, L. A., & Farmer, R. G. (1992). Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Comparison with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Archives of neurology, 49(12), 1237–1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1992.00530360035014

- Mustač, F., Pašić, H., Medić, F., Bjedov, B., Vujević, L., Alfirević, M., Vidrih, B., Tudor, K. I., & Bošnjak Pašić, M. (2021). Anxiety and depression as comorbidities of multiple sclerosis. Psychiatria Danubina, 33(Suppl 4), 480–485.

- Goretti, B., Portaccio, E., Zipoli, V., Hakiki, B., Siracusa, G., Sorbi, S., & Amato, M. P. (2009). Coping strategies, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology, 30(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-008-0009-3

- Washington, F., & Langdon, D. (2022). Factors affecting adherence to disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: Systematic review. Journal of neurology, 269(4), 1861–1872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10850-w

- Greenberg, B., Fan, Y., Carriere, L., & Sullivan, A. (2017). Depression and age at first neurology appointment associated with receipt of behavioral medicine services within 1 year in a multiple sclerosis population. International journal of MS care, 19(4), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2016-012

- Taylor, P., Dorstyn, D. S., & Prior, E. (2020). Stress management interventions for multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of health psychology, 25(2), 266–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319860185

- Mohr, D. C., Lovera, J., Brown, T., Cohen, B., Neylan, T., Henry, R., Siddique, J., Jin, L., Daikh, D., & Pelletier, D. (2012). A randomized trial of stress management for the prevention of new brain lesions in MS. Neurology, 79(5), 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182616ff9

- Turner, A. P., & Knowles, L. M. (2020). Behavioral interventions in multiple sclerosis. Federal practitioner: For the health care professionals of the VA, DoD, and PHS, 37(Suppl 1), S31–S35.

- Sesel, A. L., Sharpe, L., & Naismith, S. L. (2018). Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for people with multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis of specific treatment effects. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 87(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000486806

- Hind, D., Cotter, J., Thake, A., Bradburn, M., Cooper, C., Isaac, C., & House, A. (2014). Cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of depression in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC psychiatry, 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-5

- Dennison, L., & Moss-Morris, R. (2010). Cognitive–behavioral therapy: What benefits can it offer people with multiple sclerosis?. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 10(9), 1383-1390.

- Mohr, D. C., Likosky, W., Bertagnolli, A., Goodkin, D. E., Van Der Wende, J., Dwyer, P., & Dick, L. P. (2000). Telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 68(2), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.356

- Pakenham, K. I., Mawdsley, M., Brown, F. L., & Burton, N. W. (2018). Pilot evaluation of a resilience training program for people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation psychology, 63(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000167

- Thompson, B., Moghaddam, N., Evangelou, N., Baufeldt, A., & das Nair, R. (2022). Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for improving quality of life and mood in individuals with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. MS and related disorders, 63, 103862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2022.103862

- Borghi, M., Bonino, S., Graziano, F., & Calandri, E. (2018). Exploring change in a group-based psychological intervention for multiple sclerosis patients. Disability and rehabilitation, 40(14), 1671–1678. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1306588